Proposals to exempt gene-edited organisms would be the most “extreme” in the world. Report: Claire Robinson

In a new expert report, independent scientists have strongly criticised the New Zealand government’s proposal to radically weaken its GMO regulations. The scientists are based at the Centre for Integrated Research in Biosafety at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand and the lead author is Prof Jack Heinemann.

The proposed legislation would remove a whole subclass of gene-edited plants, animals, and microbes from the scope of the GMO regulations,[1] meaning that they would be exempted from pre-market risk assessment for health and the environment, traceability requirements, and GMO labelling. In short, they’d be treated just the same as non-GM.

The gene-edited GMOs to be exempted are those classed as the products of SDN1 (gene disruption) and SDN2 (gene modification). As with the recent deregulation of gene-edited GMOs in England, the New Zealand government assumes that these organisms could also arise from conventional breeding, so no special regulation is needed.

The New Zealand government has opened a public consultation on the proposals, with the comment period closing on 17 February.

Prof Jack Heinemann and his colleagues have submitted a detailed expert report in which they warn that if the bill passes, “New Zealand would have the most extreme combination in the world of proposed species brea[d]th (microorganisms, plants, animals) and process (e.g. SDN2) exemptions without the safety net of a case-by-case confirmation step prior to release.”

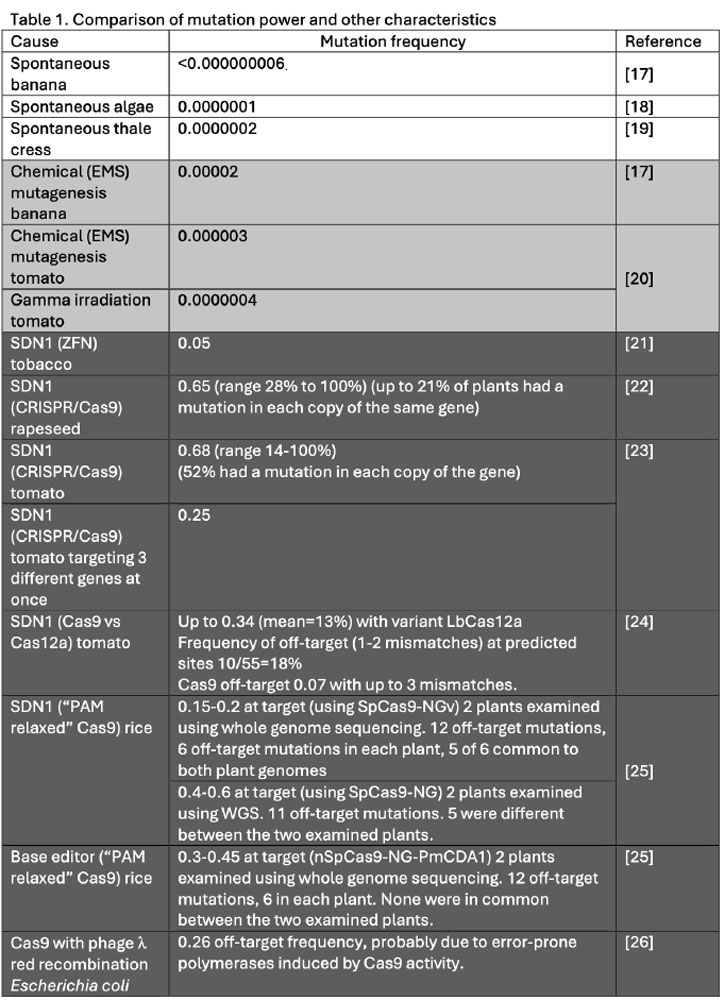

Using peer-reviewed evidence, the scientists show that gene editing is 1000-10,000 times more damaging to plant genomes than chemical and radiation-based mutagenesis, which in turn is far more damaging than natural reproduction. These facts debunk claims made by governments and industry that gene editing is less mutagenic and disruptive to the genome than natural reproduction and even random mutagenesis breeding.

Interestingly, according to the report, Australia, which has already deregulated SDN1, defines SDN2 as distinguishable from conventional breeding – meaning the two closely aligned nations would have conflicting regulatory standards if New Zealand’s deregulatory bill passes. SDN2, which involves the intentional modification of a gene using a DNA "repair template", has a potentially higher chance than SDN1 of creating a very different organism from the non-GM parent, which is why Australia hasn’t deregulated it. However, the scientists note in their report that even the US Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), states that SDN1, SDN2, and each or both in multiple reactions, can create outcomes with no known equivalent in conventional breeding. If New Zealand’s deregulation lobby gets its way, the country would have weaker GMO regulations than even the US – an extraordinary situation, given the traditional caution that it has exercised over GMO releases.

While New Zealand is an outlier in the scope of its deregulatory ambitions, the same arguments that it’s using are being repeated everywhere to justify smoothing the path to market for new gene-edited GMOs. So the scientists’ expert report can be used to oppose these moves in many countries across the world.

Promises, promises

GMO developers have long been lobbying for such deregulation on the back of evidence-free promises – and New Zealand is no exception. AgResearch’s Dr Tony Conner wrote in the press that due to the country’s GMO regulations, “Missed opportunities for New Zealand scientists working at the forefront of global developments include the development of vegetables that are more resistant to pests and diseases”, meaning, according to him, less pesticide use and increased sustainability, as well as a “tear-less” onion. Needless to say, there are no such gene-edited GMOs on the market or close to commercialisation.

The MP Judith Collins, who is promoting the deregulation bill, used Twitter/X to add to the hype with her own collection of promises, seemingly based on “fear of missing out” (FOMO): “New Zealanders will soon be able to join other citizens of advanced economies and access science that improves lives, health, the environment, productivity, and brings us into line with mainstream thought and practice.”

Few of her X followers seemed convinced, with one replying, “I really wish we demanded MPs provide sources to scientific evidence that backed statements like this. In this day and age it’s not hard for you to provide evidence to support claims and without them you just come across as a poor communicator.”

Prof Heinemann dismissed claims that keeping GMOs regulated risked New Zealand being left behind. He told the Science Media Centre of New Zealand that on the contrary, deregulating according to the government’s proposals would make the country “an international minority in its combination of deregulated gene technology processes and organisms. The basis for this change is that there is one world view of what outcomes of conventional breeding are identical to those made using gene technology. The world doesn’t have one view on this despite attempts to make it appear otherwise.”

In their expert report, the critical scientists debunk the FOMO argument in detail, in a section called “But all our friends are doing it” (deregulating gene editing). They write, “According to the latest data from Food Standards Australia New Zealand… when it comes to making GMOs only 31 (including New Zealand) of 195 countries (16%) have consultation processes underway that might – or might not – lead to changes in the equivalent of their gene technology laws. Only 11% (21 countries including Australia) have taken steps to change their laws. As of December 2024, the United States has reversed its legal position, reducing to 20 the number of countries revising regulations.”

They add, “Of all countries that have changed their gene technology laws, only Canada and Australia have no mandatory notification requirement (and for Canada, changes are restricted to only plants).” Yet under the New Zealand proposal, notification requirements would not apply to exempted GMOs, meaning that no one would know what’s out there and no one could trace the source if something goes wrong.

Proposed reforms based on “idealised” view of GM

The New Zealand government, in common with every pro-deregulation government, claims that the gene-edited organisms to be exempted are indistinguishable from those arising from natural breeding and that therefore there is no need to regulate them. But Prof Heinemann told the Science Media Centre, “That is not scientifically justified.”

In their report, the scientists explain: “The proposed reforms are based on idealised and superficial descriptions of gene technology. The idealised outcome of indistinguishable from conventional breeding is only one of many products made every time gene technology is used. The ideal outcome must be identified and confirmed from amongst the mix of organisms made.”

The report adds, “The proposed legislative trigger for a regulated tier is products and processes that create outcomes distinguishable from conventional breeding. This trigger inevitably leads to future semantic disputes of what conventional breeding means, and technical challenges to distinguishability. These debates and contests aren’t focussed on safety and are not efficient ways to regulate.”

In answer to the government’s stance that the hazards of gene editing can be indistinguishable from those of conventional breeding, the report says it doesn’t follow that all products of gene technology should be exempt from risk assessment prior to release: “It isn’t just that nature or conventional breeding could plausibly make something undesirable to human health or the environment, it is that without technology those things happen at profoundly lower frequencies and in fewer locations where they can cause harm. Failure to regulate a hazard created by one kind of technology, conventional breeding, is not an excuse to ignore a hazard created by another, such as gene technology.”

Referring to the numerous unexpected outcomes of gene technologies such as gene editing, Prof Heinemann told the Science Media Centre, “The legislation risks trade disputes and environmental degradation based on unrealistic expectations that the technology mainly creates what we want it to. That can’t be assumed. It is regulations on gene technology, not gene technology itself, that ensures we know what we made.”

Dangers of ignoring process

The critical scientists, in their report, warn against ignoring the process of creating gene-edited organisms – a tactic used by all deregulatory moves, including England’s Genetic Technology Act of 2023. That’s because, as the report says, “Process can inform the potential for the organism to have a change that might make it a hazard.” The scientists note that the US National Academies of Science and Medicine (NASEM), in its 2016 update on gene technology applied to plants, recommended routine use of “omics” molecular analysis techniques to find unintended changes in composition (such as the production of toxins or allergens) caused by the gene editing process. This is also something that GMWatch and many scientists have consistently recommended. In contrast, the deregulation lobby only wants to consider the intended end product – which would miss all the unintended effects caused by the gene editing process.

Gene editing is a far more powerful mutagen than chemicals or radiation

Mutations are genetic errors or damage that can cause genes to malfunction. While they can happen in nature (in some cases leading to disease or abnormalities), a few plant breeders have sought to increase the mutation rate by subjecting seeds or other plant material to chemicals or radiation, in the hope of creating a desirable new trait. These techniques, also known as random mutagenesis, have been used for decades, but they have proven to be both risky and inefficient, creating large numbers of non-viable and deformed plants – leading to a steep decline in use since their heyday in the 1980s and 90s.

Gene editing is specifically designed to create mutations, also in the hope that a useful new or modified trait will result. The technology is therefore a powerful mutagen (creator of mutations). The important difference between gene editing and random mutagenesis is that with gene editing, the genetic engineer can create a break in the DNA at a predetermined sequence in the genome. The subsequent repair of the DNA forms the “gene edit”. This repair is not fully under the control of the genetic engineer. It’s an imprecise process that can cause widespread damage to the genome.

Mutagens such as chemicals and radiation are recognised as dangerous substances and regulations around the world have been put in place to reduce or eliminate our exposure to them.

But now the New Zealand government wants to exempt an especially powerful mutagen – gene editing – from regulation. The critical scientists, in their report, call out this extreme position: “All other powerful mutagens, including chemical and radiation mutagens, are treated with significantly more oversight and control for safety reasons… Despite their powerful mutagenic properties, the proposed legislation would treat the combination of biological/chemical vectors used for gene editing and the gene editors themselves (e.g. CRISPR/Cas, ZFNs, TALENs) differently to other powerful mutagens by excluding some uses from legislative scope or notification requirements.”

The critical scientists point out in their report: “Chemical and radiation-based gene technology is comprehensively regulated despite them being by some measures approximately 1000-10,000 times less potent than gene editing and silencing tools.”

As evidence for this figure, the scientists have compiled a remarkable table (p16 and reproduced below), based on peer-reviewed evidence in plants, showing that gene editing – including so-called SDN1 applications, which the New Zealand government wants to exempt from regulation based on the assumption that the organisms produced with it are conventional-like – is a far more powerful mutagen than conventional breeding or even chemical- and radiation-induced mutagenesis. In other words, gene editing creates mutations at a far greater frequency than chemical- and radiation-induced mutagenesis, which in turn creates mutations at a far greater frequency than occurs in nature.

This evidence directly challenges claims made by governments and industry in many countries that gene editing is less mutagenic and disruptive to the genome than natural reproduction and even random mutagenesis breeding.

This upscaling of mutations through gene editing and other GM technologies means increased risk over and above anything that nature can come up with, as Prof Heinemann and co-authors explained in a peer-reviewed publication. And this matters, a lot. Mutations can change gene function, and in plants, altered gene function can result in altered biochemistry, including the production of toxins or allergens. Apart from risks to the consumer, unexpected effects on wildlife are other possible outcomes.

In GM animals, altered gene function can cause severe health and welfare problems, as were seen in New Zealand’s government-funded GMO research programmes.

Risks not contained

The New Zealand government’s proposals would end for exempted GMOs the traditional requirement for containment during research and development prior to approved environmental release. This means any foolish or irresponsible person with a CRISPR kit (easily purchased online) can experiment with gene editing in their kitchen or garage – and anyone can be exposed to the results of their efforts. That could include gene-edited microorganisms. In their expert report, the scientists warn that “New pathogens can inadvertently be created by exempt/non-notifiable activities”.

Heavy duty support from unexpected source

In their expert report, the scientists cite heavy duty backup for many of the points they make – from none other than NASEM. That may seem surprising, given the row that exploded at the time of the release of the NASEM update, about the pro-GMO bias of some of its content, as well as the conflicts of interest in the report’s authors and the NASEM itself. Yet in spite of the clear pro-GMO bias of parts of the update, NASEM still manages to show a certain responsibility and caution that is entirely absent from the New Zealand government’s proposals – as well as England’s Genetic Technology Act.

As an example of its precautionary approach to gene technologies, NASEM said, “In many cases, there may be substantial uncertainty about whether there is a hazard at all or how severe the hazard is. As technology provides plant breeders with more powerful tools, it creates the potential to introduce novel traits with which breeders and regulators have no clear comparators or experience. Such cases may be rare, but given the potential for novel exposure, it is a reasonable policy response to review such plants before their release into the environment. Risk managers can obtain additional information under field trial conditions requiring containment and other risk-mitigation measures intended to prevent uncontrolled releases.”

NASEM also debunks the notion that “small” changes made to the genome via gene technologies should be exempt from regulation, saying (in common with GMWatch and many scientists), “even a small genetic change could lead to biologically important alterations of a crop, so it would not be possible to exempt plants with small genetic changes”.

This is all sensible advice – with which the critical scientists agree – but which the New Zealand government wants to throw to the wind.

What deregulation is really about

Of course, what the deregulation bill is really about – in common with similar deregulation moves across the globe – is abolishing GMO labelling. It’s a crude attempt to avoid consumer resistance to GMOs and evade liability when and if something goes wrong.

What do farmers say?

Farmers have spoken out against the deregulation bill, saying it will trade away “our GE-free competitive advantage” and that “the costs… will fall on farmers and supply chains”.

What do campaigners say?

According to the campaign group GE Free NZ several important issues are excluded from the bill:

* No precautionary principle

* No protection for nature

* No liability on users of genetic engineering to ensure they manage risks

* No supply chain segregation devoted to separation and identity preservation

* No labelling of exempted genetically engineered organisms to preserve farmer and consumer choice

* No specified standard for ethics or to prevent animal cruelty

* No economic consideration of the value of non-GMO exports

* All references to genetic modification and gene editing are removed from legislation

* All exempted (not regulated) genetically engineered products, plants and seeds (SDN1, SDN2) will be allowed to enter New Zealand unlabelled and untested for safety and considered as non-genetically engineered.

The group says these exclusions endanger New Zealand’s environment, exports, farmers’ livelihoods, and the public interest. There are more details and advice on how to have your say to the New Zealand government authorities on the GE Free NZ website.

Physicians & Scientists for Global Responsibility have published an excellent video interview with Prof Jack Heinemann about the New Zealand government proposals – and the scientific case against them. It’s well worth watching.

Notes

1. Currently in New Zealand, GMOs are regulated under the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996.

Heinemann et al's primary submission and supplementary submission are available here. Scroll down to see the supplementary submission link.

The submission by GMWatch's Claire Robinson and Prof Michael Antoniou is here.