“This is a restraining order for all genome editors to stay the living daylights away from embryo editing” – gene editing expert

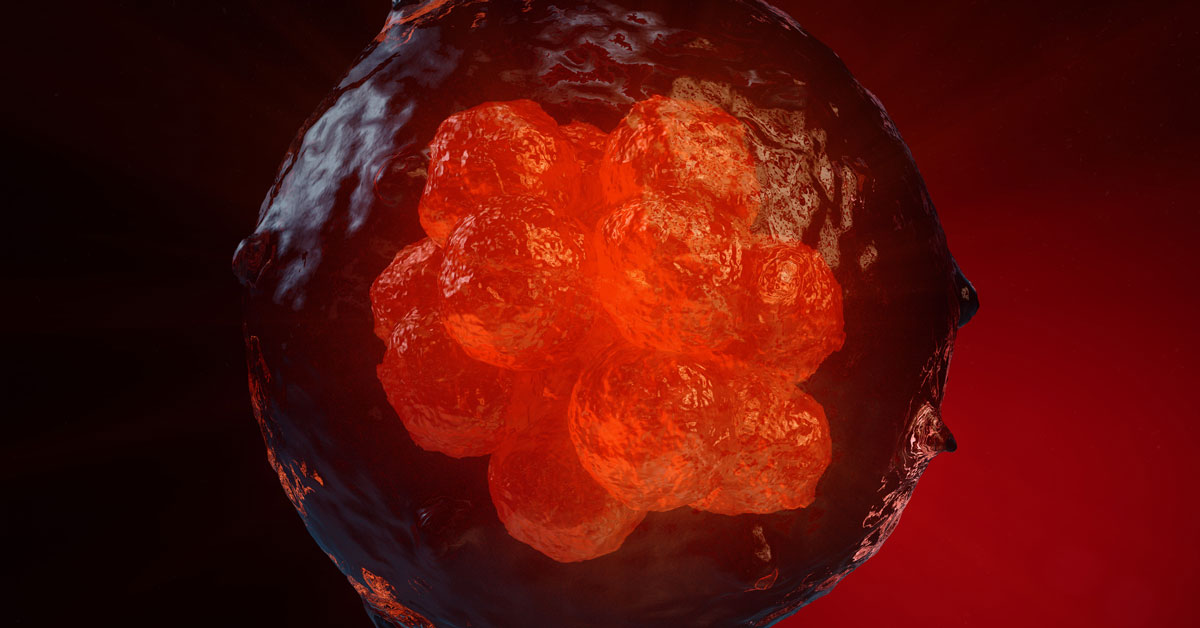

Scientists using the gene editing technique CRISPR to edit human embryos found that around half of the edited embryos contained major unintended edits in the form of deletions or additions of DNA directly adjacent to the edited gene – see the article below.

The article contains a comment by Fyodor Urnov, a gene-editing expert and professor of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley, who says, “There’s no sugarcoating this. This is a restraining order for all genome editors to stay the living daylights away from embryo editing.”

We couldn't have put it better ourselves.

What these researchers have found to happen in human embryos has also been found to occur in numerous past studies in somatic cells – that is, large deletions and rearrangements of the genome at the intended editing site following the CRISPR-Cas double-strand DNA breakage. Are we surprised? Not at all.

These on-target mutations will be in addition to the inevitable off-target mutations, which the authors do not appear to have looked at.

The research was carried out by biologist Kathy Niakan and her team at the Francis Crick Institute in the UK.

The pre-print referred to in the article below is available here.

Germline gene editing "not safe"

Commenting on the new findings for the Center for Genetics and Society, Dr Katie Hasson wrote:

"Some proponents of heritable genome editing have recently asserted that scientists are well on their way to solving known safety and technical issues, such as off-target edits. This clear evidence from Niakin’s lab of additional on-target risks lends even more support to the countervailing views of many scientists (some of whom called in Nature for a moratorium) that germline [heritable] genome editing is not safe and should not be used for reproduction.

"There are, of course, grave societal and ethical concerns about heritable genome editing that go far beyond these safety and technical issues (and there are accompanying calls to provide time for both public deliberation and a 'course correction' that would ensure discussions are informed, inclusive, and impactful).

"But current public, policy, and ethical discussions are often premised on a hypothetical situation in which heritable genome editing is proven 'safe and effective', giving the sense that we are closer to that situation than we may ever get.

"Hopefully, this new evidence will catch the attention of the multiple international committees currently drafting reports and guidelines on the governance of heritable human genome editing. We don’t need more reasons to reject heritable human genome editing, but they do seem to be piling up."

Plants too

The new findings follow close upon a paper that found a wide range of undesirable and unintended on-target and off-target mutations in CRISPR-edited rice plants. The authors warned that "early and accurate molecular characterization and screening must be carried out for generations before transitioning of CRISPR/Cas9 system from lab to field" and that “Understanding of uncertainties and risks regarding genome editing is necessary and critical before a new global policy for the new biotechnology is established".

In spite of all this, a misguided faction of German Greens is calling for the de-regulation of gene-edited foods and crops. When will they – and others swallowing the CRISPR hype – wake up and take note of what's actually happening in the gene-editing labs?

---

Scientists edited human embryos in the lab, and it was a disaster

Emily Mullin

Medium OneZero, 16 Jun 2020

https://onezero.medium.com/scientists-edited-human-embryos-in-the-lab-and-it-was-a-disaster-9473918d769d

* The experiment raises major safety concerns for gene-edited babies

A team of scientists has used the gene-editing technique CRISPR to create genetically modified human embryos in a London lab, and the results of the experiment do not bode well for the prospect of gene-edited babies.

Biologist Kathy Niakan and her team at the Francis Crick Institute wanted to better understand the role of a particular gene in the earliest stages of human development. So, using CRISPR, they deleted that gene in human embryos that had been donated for research. When they analyzed the edited embryos and compared them to ones that hadn’t been edited, they found something troubling: Around half of the edited embryos contained major unintended edits.

“There’s no sugarcoating this,” says Fyodor Urnov, a gene-editing expert and professor of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley. “This is a restraining order for all genome editors to stay the living daylights away from embryo editing.”

While the embryos were not grown past 14 days and were destroyed after the editing experiment, the results provide a warning for future attempts to establish pregnancies with genetically modified embryos and make gene-edited babies. (The findings were posted online to the preprint server bioRxiv on June 5 and have not yet been peer-reviewed.) Such genetic damage described in the paper could lead to birth defects or medical problems like cancer later in life.

Since CRISPR’s debut as a gene-editing tool in 2013, scientists have touted its possibilities for treating all kinds of diseases. CRISPR is not only easier to use but more precise than previous genetic engineering technologies — but it’s not foolproof.

Niakan’s team started with 25 human embryos and used CRISPR to snip out a gene known as POU5F1 in 18 of them. The other seven embryos acted as controls. The researchers then used sophisticated computational methods to analyze all of the embryos. What they found was that of the edited embryos, 10 looked normal but eight had abnormalities across a particular chromosome. Of those, four contained inadvertent deletions or additions of DNA directly adjacent to the edited gene.

A major safety concern with using CRISPR to fix faulty DNA in people has been the possibility for “off-target” effects, which can happen if the CRISPR machinery doesn’t edit the intended gene and mistakenly edits someplace else in the genome. But Niakan’s paper sounds the alarm for so-called “on-target” edits, which result from edits to the right place in the genome but have unintended consequences.

“What that means is that you’re not just changing the gene you want to change, but you’re affecting so much of the DNA around the gene you’re trying to edit that you could be inadvertently affecting other genes and causing problems,” says Kiran Musunuru, a cardiologist at the University of Pennsylvania who uses CRISPR in his lab to research potential heart disease therapies.

If you think of the human genome — a person’s entire genetic code — as a book, and a gene as a page within that book, CRISPR is like “ripping out a page and gluing a new one in,” Musunuru says. “It’s a very crude process.” He says CRISPR often creates small mutations that are probably not worrisome, but in other cases, CRISPR can delete or scramble large sections of DNA.

This isn’t the first time scientists have used CRISPR to tweak the DNA of human embryos in a lab. Chinese scientists carried out the first successful attempt in 2015. Then, in 2017, researchers at the Oregon Health and Science University in Portland and Niakan’s lab in London reported that they’d carried out similar experiments.

Ever since, there have been fears that a rogue scientist might use CRISPR to make babies with edited genomes. That fear became reality in November 2018, when it was revealed that Chinese researcher Jiankui He used CRISPR to modify human embryos, then established pregnancies with those embryos. Twin girls, dubbed Lulu and Nana, were born as a result, sending shockwaves throughout the scientific community. Editing eggs, sperm, or embryos is known as germline engineering, which results in genetic changes that can be passed on to future generations. Germline editing is different from the CRISPR treatments currently being tested in clinical trials, where the genetic modification only affects the person being treated.

While many scientists have opposed the use of germline editing to create gene-edited babies, some say it could be a way to allow couples at high risk of passing on certain serious genetic conditions to their children to have healthy babies. Beyond preventing disease, the ability to edit embryos has also raised the possibility of creating “designer babies” made to be healthier, taller, or more intelligent. Scientists almost universally condemned He’s experiment because it was done in relative secrecy and it wasn’t meant to fix a genetic defect in the embryos. Instead, he tweaked a healthy gene in an attempt to make the resulting babies resistant to HIV.

In the United States, establishing a pregnancy with an embryo that has been genetically modified is prohibited by law. More than two dozen other countries directly or indirectly prohibit gene-edited babies. But many countries have no such laws. Since He’s fateful gene-editing experiment became public, a researcher in Russia, Denis Rebrikov, has expressed interest in editing embryos from deaf couples in an attempt to provide them with babies that can hear.

Niakan could not be reached for comment, but in a December 2019 editorial in the journal Nature, she argued that much more work on the basic biology of human development is needed before gene editing can be used to create babies. “One must ensure that the outcome will be the birth of healthy, disease-free children, without any potential long-term complications,” she wrote.

The embryos edited by Niakan and her team were never intended to be used to start a pregnancy. In February 2016, her lab became the first in the U.K. to receive permission to use CRISPR in human embryos for research purposes. The embryos used are left over from fertility treatments and donated by patients.

Niakan’s paper comes as the U.S. National Academies, U.K.’s Royal Society, and the World Health Organization are contemplating international standards around the use of germline genome editing in response to the global outcry over He’s experiment. The committees are expected to release recommendations this year or in 2021. But because these organizations have no enforcement power, it will be up to individual governments to adopt such standards and make them law.

Urnov says the new findings should influence those committee’s decisions in a substantial way.

Musunuru agrees. “Nobody has any business using genome editing to try to make modifications in the germline,” he says. “We’re nowhere close to having the scientific ability to do this in a safe way.”