Never mind the insect apocalypse, here comes the pesticide-resistant techno-fix. Report by Jonathan Matthews

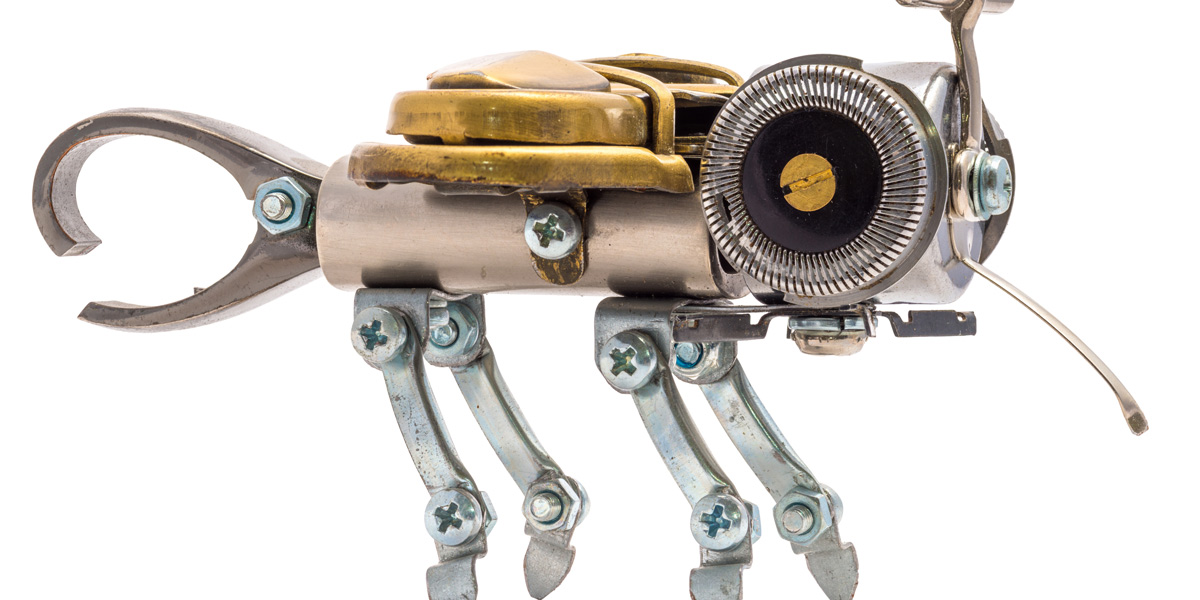

“Robotic bees could pollinate plants in case of insect apocalypse”, ran a recent Guardian headline reporting how Dutch scientists “believe they will be able to create swarms of bee-like drones to pollinate plants when the real-life insects have died away”.

And that’s not the only techno-fix on offer for the mass extinction of pollinators. Also in the works are GMO bees, including ones resistant to pesticides, which are a key contributor to the crisis engulfing insects around the globe.

Are robotic bees the future?

Over 75% of the leading types of global food crops are reliant on pollinators and the FAO says their help is worth hundreds of billions of dollars a year. So it’s hardly surprising that Walmart is among those filing patents on robotic bees.

But Jeff Ollerton, a leading expert on pollination ecology, calls claims that robots are the fix for pollinator wipe-out “complete bullshit”. According to Ollerton, “No one who knows anything about pollinators thinks that this is feasible... Each year it takes at least 22 trillion pollinator visits to the flowers of coffee plants to sustain global coffee production. That's one crop.”

Bee expert Dave Goulson is equally unimpressed. In his article, “Are robotic bees the future?”, he also points to the numbers. To take care of insect pollination, robotic bees would need to replace “countless trillions” of insects – “All to replace creatures that currently deliver pollination for free.”

It’s not just the mind-boggling scale and expense of replacing pollinators that concerns experts like Goulson and Ollerton. They also point to the environmental costs: the resources and pollution involved in producing a vast army of pollinating drones, the energy costs for running them, and the disposal/pollution costs when they stop working. In contrast, real bees, says Goulson, in addition to being biodegradable, “avoid all of these issues; they are self-replicating, self-powering, and essentially carbon neutral”.

Goulson also points out, “Bees have been around and pollinating flowers for more than 120 million years; they have evolved to become very good at it. It is remarkable hubris to think that we can improve on that.”

Send in the GMO bees

But “another controversial response to the slump in bee populations” aims to do exactly that, according to a recent article by Bernhard Warner in The Guardian. Instead of replacing pollinators, this techno-fix involves genetically engineering “more resilient” strains of the honeybee that could better survive the hazards of pesticides, as well as the bee viruses and parasites that humans have spread around the globe.

The first honeybee queen was successfully genetically engineered in 2014 in a Düsseldorf lab. Its director Martin Beye says his lab is simply exploring the genetic basis of bee behaviour and not trying to build a GMO bee for release into the wild.

But according to Bernhard Warner: “The truth is that Beye’s highly detailed paper serves as a kind of blueprint for how to build a bee. Thanks to research like his, and the emergence of tools such as CRISPR, it has never been cheaper or so straightforward for a chemical company to pursue a superbee resistant to, say, the chemicals it makes. Takeo Kubo, a professor of molecular biology at the University of Tokyo, was the second scientist in the world to make a genetically modified bee in his lab. He told me that he, too, is focused on basic research, and has no ties to the agriculture industry. But, unlike Beye, he welcomes the prospect of GM bee swarms buzzing around the countryside. Lab-made, pesticide-resistant bees could be a real saviour for beekeepers and farmers, he says. And, he adds, the science is no more than three years away.”

“I’m now 57 years old,” he told Warner in an email, “and completely optimistic to see such transgenic bees in the marketplace in my lifetime!”

Many beekeepers are understandably alarmed. According to Warner, “Beekeepers fear genetic engineering of honeybees will introduce patents and privatisation to one of the last bastions of agriculture that is collectively managed and owned by no one.” They also fear that GM bees will pollute the gene pool of traditional honeybees and destroy the vibrant local market in such strains.

Warner says there are also health concerns. Bee stings can already produce allergic reactions in some people that range from the mild to the life-threatening. Could the sting of GM bees “introduce new allergy risks”?

And there are ecological concerns. Honeybees can already out-compete wild bees, posing a real problem in areas of limited forage where wild bee species are under threat. So wouldn’t smaller struggling bee species face an even bigger threat from a pesticide-resistant “superbee”?

Throwing nature under the bus

There is a still more fundamental problem with projects that envisage changing or replacing bees to accommodate intensive farming practices. Jay Evans, who heads the bee research lab at the US Department of Agriculture, told Warner that designing a pesticide-proof honeybee, or a “bulletproof bee”, as Evans calls them, would “throw a lot of nature under the bus”.

Dave Goulson sees exactly the same problem with robotic bees. “If farmers no longer need to worry about harming bees they could perhaps spray more pesticides, but there are many other beneficial creatures that live in farmland that would be harmed; ladybirds, hoverflies and wasps that attack crop pests, worms, dung beetles and millipedes that help recycle nutrients and keep the soil healthy, and many more. Are we going to make robotic worms and ladybirds too? What kind of world would we end up with?”

In other words, technologists intent on propping up a form of agriculture where farmers don’t need to worry about harming bees are actually fueling the devastating trajectory that is already causing massive insect declines. And, as a recent Guardian editorial noted, the global collapse of insect numbers is in turn a threat to almost every other species on the planet.

Even the GMO bee pioneer Martin Beye agrees that building a GMO bee is “a stupid idea”. Rather than pesticide-proof bees, he told Warner, we need to move to farming practices that don’t harm bees. “They should be working on that. Not on manipulating the bee.”

Dave Goulson puts it like this, “Do we have to always look for a technical solution to the problems that we create, when a simple, natural solution is staring us in the face? We have wonderfully efficient pollinators already, let’s look after them, not plan for their demise.”