By Lysiane Lefebvre, David Laborde, and Valeria Piñeiro

As the food and climate crises continue to cause suffering around the world, one under-appreciated solution — neglected crops — could be a powerful tool to alleviate both crises in one of the worst affected regions: Africa.

Neglected crops — including grains such as sorghum and millet and vegetables such as amaranth, eggplant, and kale — are also known as “indigenous”, “lost”, “native”, “orphan”, “traditional”, or “underutilised” crops, or as ingredients in “forgotten foods”. These terms capture various aspects of these important crops: They are indigenous or native to a specific region (e.g., regions in Africa); they have traditionally been the basis for highly nutritious foods, but over time, they were lost or forgotten by many and thus orphaned; and they are now underutilised by farmers and producers and, likewise, neglected by consumers, plant breeders, policymakers, and donors.

Bringing back neglected crops is not a new topic, but the idea has gathered new momentum in 2023, which the United Nations has declared the International Year of Millets. This post makes a case for reintroducing and scaling up cultivation and use of these crops, which offer a promising way to address both the food and climate crises — particularly for Africa.

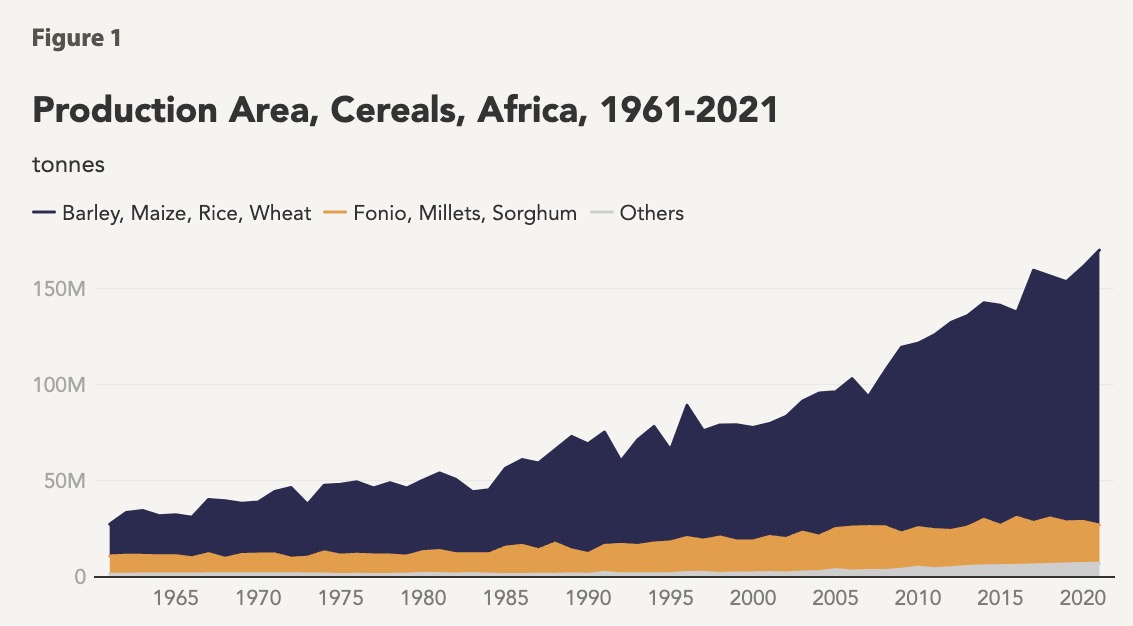

Neglected crops were traditionally cultivated for subsistence, but during the 20th century were gradually displaced by crops better suited to commercial farming. The globalising agrifood sector grew increasingly specialised, intensified, and concentrated. Along with modernisation and urbanisation, the search for ever more efficiency and productivity led to the dominance of very few (arguably too few) food sources. A handful of staple crops replaced the once-wide range of subsistence crops; 75% of crop varieties disappeared over the 20th century. In 2020, only three plant crops (maize, rice, and wheat) accounted for 41% of the world’s caloric intake. As Figure 1 shows, the growth in production area of these three main crops (in blue) in Africa has far outpaced that of traditional cereals (in orange), like sorghum and millet.

Neglected crops were abandoned as producers focused on fewer, more profitable crops, and as consumers preferred more convenient crops that could more easily be processed into food products.

Why bring back neglected crops? Part of the answer lies in increasing the number of food options and diversifying markets in order to create a more secure global food supply in the face of more frequent shocks.

The multiple crises of recent years have revealed many weaknesses in food systems. Events including local and global economic downturns, political and military conflicts, climate-driven extreme weather events, pandemics including COVID-19, and pests and crop diseases, have combined to push food prices up and millions of people into hunger. These crises have hit Africa especially hard, and it remains at high risk: More than one in five Africans, or 278 million people, suffer from chronic hunger, and food price inflation in Africa exceeded 20% in June 2022 (its highest level since tracking of the indicator began more than 20 years ago).

Climate change impacts are especially significant: On the one hand, these are already affecting food security and nutrition and expected to continue reducing crop productivity; on the other, food systems are responsible for 34% of global gross greenhouse gas emissions. Again, these impacts fall heavily on Africa. Extreme weather events in the Horn of Africa, for example, are expected to worsen food insecurity and hamper progress toward reducing malnutrition, raising the number of people facing crisis or worse to 23-26 million if the ongoing drought extends for a fifth season.

How can neglected crops be part of the solution in Africa?

Expanding the use of neglected crops can help to diversify agriculture and food systems and introduce a greater variety of foods into global supplies—including more nutritious cereals, fruits and vegetables, and roots and tubers — while building resilience to climate change and providing employment and alternate sources of income for farmers. With parallel interventions and appropriate investments, including in additional agricultural production, diversification of food sources can help reduce consumer vulnerability to food price volatility and increase consumer food price stability.

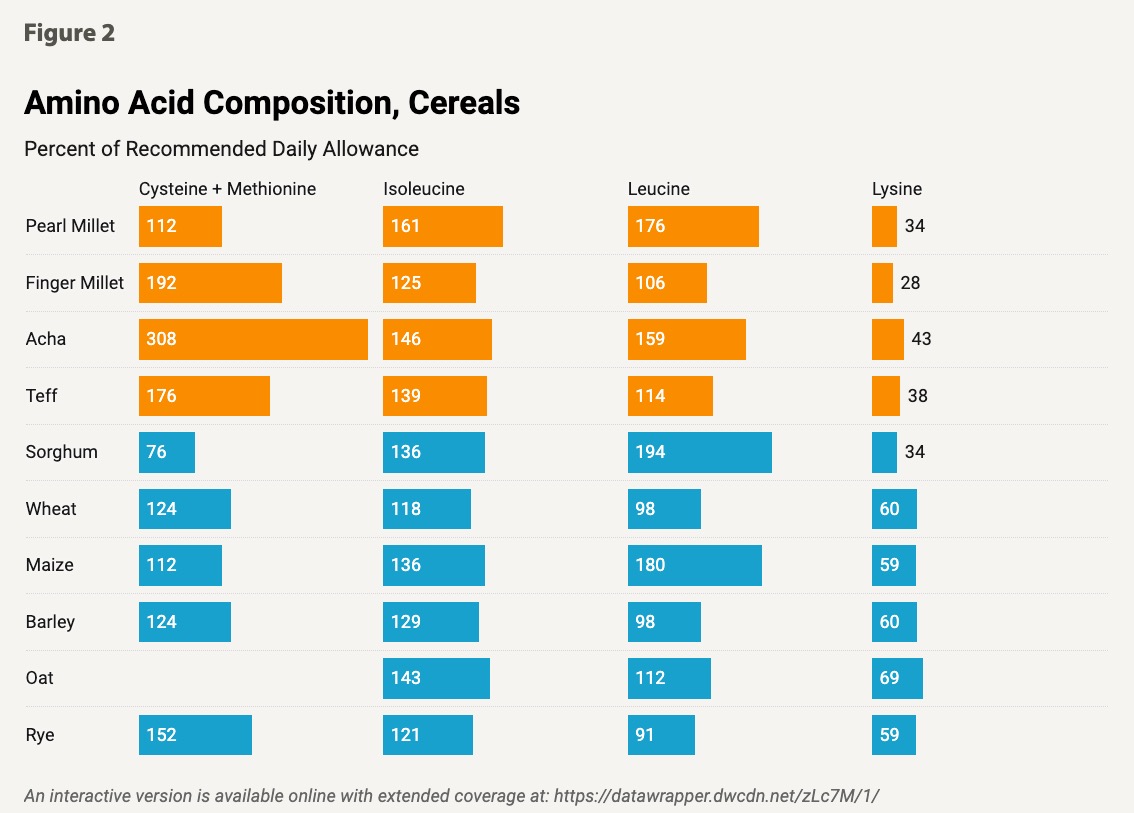

Neglected crops also offer a range of options for enhancing dietary diversity. Many have relatively high nutrient density, which makes them particularly appealing. Many neglected staple crops are also more nutritious than dominant staples. Finger millet, fonio, and teff have higher iron contents than maize, rice, and wheat—though the latter three continue to displace the former (see Box 1). As shown in Figure 2, traditional cereals (in orange) also have a relatively higher amino acid content than non-native crops (in blue). Amino acids are essential for human health and contribute to better nutrition.

The nutrition benefits of neglected crops are especially important in view of Africa’s malnutrition and poverty problems. Low incomes are generally associated with less nutritious diets which, in turn, lead to a number of public health concerns. Thus, improving the availability and maintaining the affordability of foods made from neglected crops offers a nutritious way to combat malnutrition and improve health outcomes, particularly for low-income households, by increasing nutrient content and diversifying diets.

Neglected crops can also be superior to dominant staples due to their inherent adaptation to the natural environment and local conditions. Neglected crops tolerate irregular rainfall and infertile soils better, thrive in dry conditions and even droughts better, and often succeed where other crops fail. They are also characterised by high water- and nitrogen-use efficiency, requiring less water and little to no chemical inputs like synthetic fertilisers and pesticides. Many are thus fit for marginal as well as mainstream cultivation in Africa, including in the arid Horn of Africa region. With Africa being particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, the tolerance of these crops to variations in rainfall and temperature is an important asset.

Because they have long been economically sidelined, neglected crops also hold huge potential for creating new markets, jobs, and income — from production through to value addition and distribution. Traditional vegetables, such as amaranth, eggplant, and kale, are already and increasingly popular among wealthier segments of the global population and gradually making their way into mainstream consumer markets. Depending on the crop, niche markets could be developed or more widespread adoption promoted for traditional cereals such as quinoa grown in Latin America.

Box 1: What is fonio and how is it helping farmers in West Africa?

Yolélé Foods is bringing back fonio, a crop cereal indigenous to West Africa. Since 2017, the company — which is U.S.-based and partners with West African farmers — has been reintroducing fonio “to create economic opportunity for smallholder farming communities; to support their biodiverse, regenerative, and climate-resilient farming systems; and to share Africa’s ingredients and flavors with the world.” According to the company’s co-founder and CEO Philip Teverow, rising wheat prices in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine emphasised “the folly of relying upon imported grain … And the folly of not turning to crops that have been adapted over millennia to the climate and the soil of West Africa.”

In 2022, the company invested in a fonio processing factory in Mali, with support from a $2 million grant from USAID. This project aligned with the company’s strategy of “building processing facilities in West Africa that can turn plants into food to be sold locally and globally” and is expected to create nearly 14,000 jobs as well as generate $4.5 million in sales for smallholder farmers over two years. The additional capacity will serve to supply Yolélé Foods as well as other international companies interested in sourcing fonio.

With information from articles published by Bloomberg, FoodNavigator and the Culinary Scoop, as well as the Yolélé Foods website.

Building value chains for neglected crops can also encourage the integration of the informal sector (which prevails in the absence of a developed market) as well as greater inclusion of rural smallholder farmers and women. As farming of traditional and less lucrative crops often falls to women, neglected crops present an opportunity to empower women farmers to expand their planting and harvesting — as long as using the crops in the kitchen is also facilitated through innovations that make their preparation easier and less time-consuming. Reviving neglected crops can also boost the role of indigenous knowledge in addressing the food and climate crises.

On its own, bringing back neglected crops is not a panacea for all food and climate problems. Reintroducing millet as a monoculture, for instance, would not generate the desired biological, crop, and dietary diversity, nor would it address the problem of degraded soils. This is why the reintroduction of neglected crops must be accompanied by policies and practices that promote alignment with the broader sustainable development agenda.

What will it take to bring back neglected crops?

The potential of neglected crops for today’s agrifood system can be unlocked with the right mix of modern and traditional technologies, approaches, and practices to ensure higher crop and economic productivity and profitability, and alignment with consumer preferences.

For example, more research and innovation are needed to evaluate and ensure the availability of nutrients in these crops, including examining the impacts of processing and storage on nutritional value. More investments and research are also needed to ensure and deliver scalability in their harvesting, processing, and distribution.

Other valuable qualities of neglected crops such as climate resilience and water-use efficiency should be promoted to farmers through carefully designed financial incentives, technical assistance, and extension services. Collecting more and better data will be important in driving investments in research and development and the design of effective programs and policies. Such needs should be addressed by the new, multi-phase, Vision for Adapted Crops and Soils (VACS) initiative, launched in February by the U.S. State Department's Office of the Special Envoy for Global Food Security, Cary Fowler, in partnership with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the African Union (AU).

Neglected crops also need viable markets and strong consumer demand. Farmers have no interest in growing unmarketable, untradeable goods; and consumers generally don’t want to eat unfamiliar foods they don’t know how to prepare. Thus, it’s important to build local and regional markets through public incentives and investments, including infrastructure development, regulations, and subsidies for actors along the supply chain, as well as procurement policies, educational and promotional campaigns, and regional trade integration on the demand side.

Expanding the adoption of neglected crops will also rely on fostering an enabling environment through measures such as improving access to land, farm inputs and financial services, and catering to different farmers’ and market preferences, education levels, and socio-economic status of households. To buttress public funding, private funds from international and domestic sources will be necessary.

Conclusion

With the right mix of interventions, neglected crops can be a sustainable food and climate-smart solution for Africa. Current lack of funding and infrastructure should not be an excuse to avoid action. If anything, this is another opportunity to meet Africa’s financing and development needs. Sustainable development actors and advocates should all rally behind reintroducing and scaling up neglected crops. Their many benefits make it clear they should be neglected no more.

Lysiane Lefebvre is Policy Advisor and Project Manager at the Shamba Centre for Food & Climate; David Laborde is Director, FAO Agrifood Economics Division and a former IFPRI Senior Research Fellow; Valeria Piñeiro is Acting Head of IFPRI's Latin American Region and Senior Research Coordinator with the Markets, Trade, and Institutions Unit. Opinions are the authors'.

This article was first published by IFPRI. It is republished by GMWatch under the OPEN ACCESS CC-BY-4.0 licence.

Image: Millet farming in South Sudan