Paper in Science condemned as “misleading” and the journal as “too credulous”. Jonathan Matthews and Claire Robinson report

Science Magazine recently published a paper in which Chinese scientists reported massive yield gains in rice, thanks to genetic engineering. The journal also promoted the research in a news piece that featured other scientists expressing their amazement at the yield gains achieved. The article suggested the same “genetic tweak” to a single gene could also turbocharge the yields of wheat and other crops.

News of this apparent breakthrough in how to boost global food supplies spread like wildfire on social media and triggered press coverage too. But now a young scientist studying plant breeding has debunked the paper’s claims and dismissed as bogus the whole idea that scientists can “solve” yield through single genes.

“That’s a big number. Amazing”

The “world's leading outlet for cutting-edge research”, as Science styles itself, made sure this GM rice study by a 13-strong team led by crop physiologist Wenbin Zhou of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, commanded maximum attention.

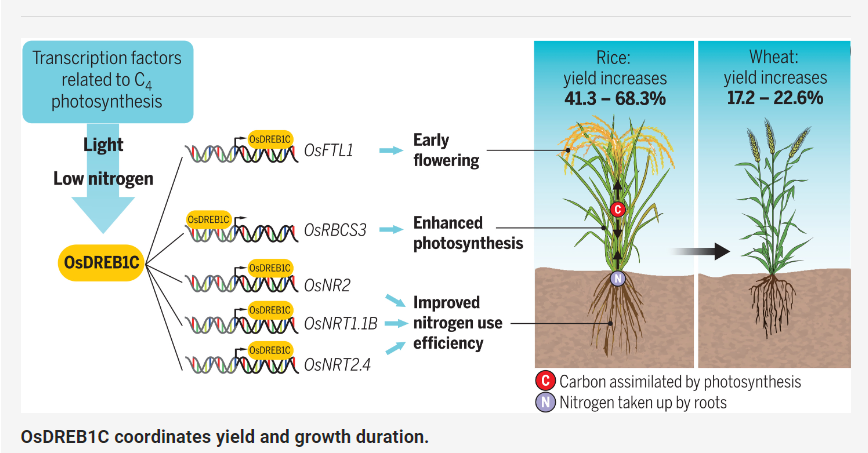

In both the Abstract and the longer Structured Abstract that Science published, the yield increases cited for the GM rice – from field trials in northern, south-eastern, and southern China from 2018 to 2021 – were 41.3 to 68.3%. In the Structured Abstract these impressive figures are also highlighted in a graphic (see image above) showing that – by overexpressing a single gene (OsDREB1C) – increases of 41.3 to 68.3% were achieved in rice, as well as 17.2 to 22.6% in wheat.

To coincide with the paper’s publication, Science commissioned a commentary, Perspective: The quest for more food, which claimed the study had revealed “a gold mine of potential for enhancing growth and yield”.

Science also ran its own news piece headlined Supercharged biotech rice yields 40% more grain, which explained how “giving a Chinese rice variety a second copy of one of its own genes… helps the plant absorb more fertilizer, boosts photosynthesis, and accelerates flowering, all of which could contribute to larger harvests”.

In case anyone wasn’t sufficiently impressed, the article went on to quote the University of California Davis’s Pam Ronald, a long-time advocate for GM crops, as saying, “That’s a big number. Amazing”. A similarly effusive Matthew Paul from Rothamsted Research, a UK institute that has undertaken extensive and sometimes controversial GM crop research, called that kind of yield gain from manipulating a single gene “really impressive”: “I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything quite like that before.”

Addressing global food shortages

Such hyperbole in a leading academic journal helped create quite a buzz on social media, with Science’s “supercharged” news piece being tweeted and retweeted innumerable times, including by scientific journals like Nature Plants and the Journal of Plant Science.

Among those commenting, Tamar Haspel, the GMO-boosting Washington Post columnist, highlighted Ronald's “That's a big number”, while David Ropeik, a risk communication consultant who typically expresses the view that risk reporting in the media is overblown, tweeted, “This is the kind of advance that knee jerk environmentalist opposition to the technology of GMOs can delay. Tribal beliefs blocking intelligent progress”. And plant developmental biologist Bart Janssen claimed, “Modern biotechnology can really make a huge difference. Typically a 1% yield increase is considered valuable enough to replace existing varieties”.

Not to be outdone, an article in the UK’s Independent newspaper set the researchers’ findings in the context of “growing food insecurity that could see millions of people face shortages and even famine this year”. According to the paper, “The scientists hope it can address global food shortages brought about by rising population growth and conflict-related supply chain issues.”

The emperor’s new data

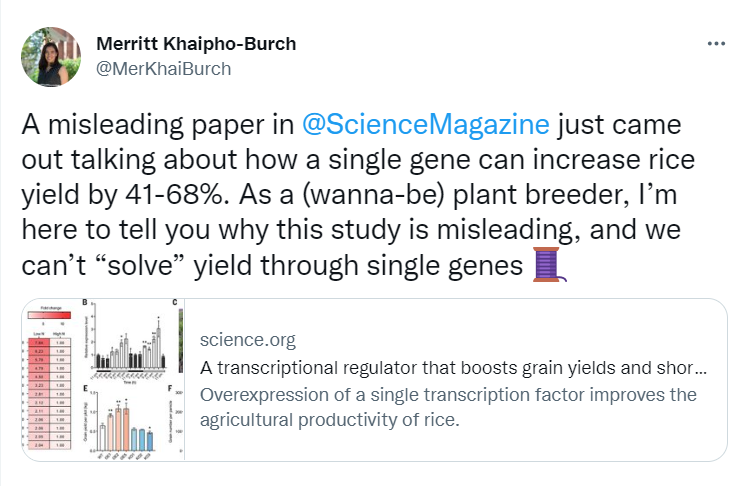

Enter Merritt Khaipho-Burch, a doctoral student at Cornell University and “(wanna-be) plant breeder” who – several days after the paper’s ecstatic reception – systematically demolished all of the hype in a Twitter thread so devastating that even Pam Ronald, whose expressions of amazement had helped boost the paper, conceded, “This is an important thread – especially for us molecular biologists interesting [sic] in improving yield”.

In their paper, as we noted, the researchers reported achieving a 41.3-68.3% higher yield in a rice variety during three years of field trials. They then replicated this approach in an elite rice variety where they again reported achieving a considerable yield increase, from about 10-40%. And, as we have seen, it is these impressive sounding numbers that generated the “supercharged” headline and talk of boosting global food supplies.

But what Khaipho-Burch pointed out was that the rice variety in which the researchers had achieved that 68.3% higher yield was “a non-commercial rice variety (Nipponbare), a genetic background not intended for yield trials” but great for genetic research because it is relatively easy to manipulate. In other words, the researchers hadn’t taken a rice variety that farmers actually grow, or that plant breeders had already developed to be high yielding, and then turbocharged that with genetic engineering.

“Incredibly low yield”

Khaipho-Burch also pointed out that their three years of field trials in three different environments were actually incredibly small scale, testing only 99-120 plants each time. “For yield trials, this is a VERY small number of plants to test for yield stability (it's usually of 1000s to millions)”.

And if you used the figures in their paper to calculate the actual amount of grain the researchers had boosted the rice to yield, then it turned out to be equivalent to just 1.16-1.39 tons of rice per hectare. Given that the average yield for Chinese rice is 6.8 tons per hectare and it can be as much as 12 tons per hectare, the trials had produced “an incredibly low yield”.

Khaipho-Burch wryly noted that “with the same vibes” as their Science paper, we could say that commercial rice varieties yield 389-763% more than the lines they had genetically engineered. She added, “There’s no Nature or Science paper for that 389-763% yield increase because it’s what plant breeders have routinely accomplished over decades of plant improvement and genetic gain” – using conventional breeding, not genetic engineering.

Another reality check

The researchers had also genetically engineered an elite variety – one that had already been bred to yield well. The engineered elite rice yielded about 7-8 tons of grain per hectare. That sounds much more impressive until you realise that in other studies this same elite variety (Xiushui134), when not genetically engineered, yields about 10 tons per hectare.

In other words, the researchers, not to mention the paper’s reviewers, had completely failed to compare their results with existing crop production. And yet their results were being hyped as evidence of a magic bullet for transforming that production via GM.

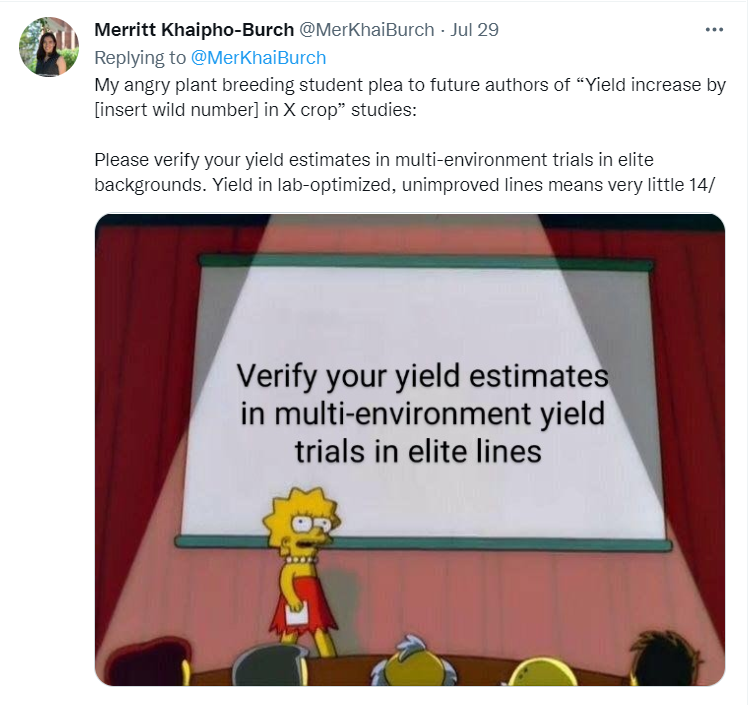

Merritt Khaipho-Burch concluded her Twitter thread by pointing out that if plant breeders want to demonstrate a consistent impact on yield, they have to conduct large-scale quality-controlled trials with elite varieties in multiple environments.

She also pointed out that hyped studies in “big-name journals” have real world consequences: “With other scientists and the public thinking plant breeders can ‘solve’ yield with 1 gene, more $$ goes into studying unreliable single gene effects” instead of the kind of traditional plant breeding that has long produced “incremental, stable and repeatable yield gains”.

Expert support

Khaipho-Burch’s thread drew mostly supportive responses, including from well-credentialed experts. The general drift of their comments was that there wouldn’t have been a problem if the authors and Science had stuck to the findings relevant to molecular biology and plant physiology, which investigates fundamental processes such as photosynthesis. The problem lay in the findings being presented as holding the key to turbo-charging commercial crop production.

Ed Buckler, a plant geneticist with the USDA Agricultural Research Service and an Adjunct Professor of Plant Breeding and Genetics at Cornell University, said Khaipho-Burch was “exactly right”: “We need to measure genetic impacts on yield in elite varieties across numerous target environments.”

Marisa Collins, Senior Lecturer in Agronomy at La Trobe University, made a wider point: “There’s great reasons to answer physiological questions in the lab but don’t extrapolate the results to suggest they apply in the field. It’s like the trend over the last 20 years of molecular studies claiming they will fix global hunger by identifying a gene.”

“One gene at a time is indeed how molecular biology is done, but it is not how crop improvement is done. The point of the thread is that many molecular biologists don't know the difference,” tweeted an account principally run by Thomas Björkman, Professor in the School of Integrative Plant Science at Cornell.

Devang Mehta, a postdoc in plant systems biology at the University of Alberta, commented, “The problem is that their results get the kind of attention that is vastly out of proportion to their narrow scope. These kinds of overblown conclusions frequently do not replicate.”

Pam Ronald admitted, “We need to set up quality field trials to accurately assess yields. Consulting with plant breeders will help.”

Seth Murray, who holds the Butler Chair in Corn Breeding and Genetics at Texas A&M University, expanded on Khaipho-Burch’s point about the disproportionate publicity and funding for genetic engineering: “An imbalance of resources to impacts is at issue. Despite 30 years and many billions spent there have been so very few molecular biology success stories in ag. Meanwhile plant breeders and agronomists keep killing it [i.e. being incredibly successful], but can't get Science papers or much funding.”

This is a point we at GMWatch have long made – that conventional plant breeding keeps leaving genetic engineering in the dust, despite getting far less exposure, funding and support. We even set up a database of non-GM plant breeding successes to demonstrate the point. We’ve also warned that attempts to achieve complex traits like high yield through genetic engineering are ultimately doomed to fail, as these traits are the result of multiple genes acting in networks and cannot be conferred by manipulating one or a few genes.

Controlling the narrative

Like the emperor triumphantly parading in his “new clothes” until a little boy pointed out he wasn’t wearing any, the GM rice study earned only plaudits until a plant breeding student spoke out. But if a student could see the problem, there must have been many more established plant breeders who also knew that the Science paper and its coverage were seriously misleading. One expert even replied to Khaipho-Burch, “I made the same calculations & reached [the] same conclusion”. But the expert doesn’t appear to have publicly shared that conclusion prior to Khaipho-Burch’s “angry plant breeding student plea”.

The Italian scholar Andrea Saltelli’s response to her thread suggests a possible reason for this apparent reticence. He warned Khaipho-Burch that if she submitted a letter about the paper’s limitations to Science or Nature, she shouldn’t hold her breath it would get published. Saltelli drew a parallel with GMO golden rice, which generated an even bigger PR extravaganza without any evidence as to its ultimate effectiveness, and how he had “tried for ages to publish on this”. Saltelli also linked to a piece he co-authored about the dangers of “forcing consensus” in science in an effort to suppress scientific and political dissent.

Establishment gatekeepers

Journals like Science play a critical gatekeeping role through what papers and letters they publish, what reviewers they select, what news stories they promote, and how they editorialise.

For instance, Science’s current editor-in-chief, Holden Thorp, is currently attracting controversy for his decidedly partisan role in the debate over the origins of COVID-19. That debate has been marked by repeated attempts to force the kind of consensus Saltelli warns against. In an interview, the early career scientist Alina Chan of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, who has pushed back hard against Holden Thorp’s view that only a zoonotic origin for the virus is credible, commented, “Somehow just raising the lab (leak) hypothesis offended a whole bunch of people, and powerful people, but behind the scenes I’ve received a lot of support… from established virologists and scientists, and they can’t go public because of their labs and their careers.”

The veteran science reporter and former New York University and University of Boston adjunct professor of journalism Michael Balter has taken a keen interest in the Covid origins debate and the lamentable part played in it by some leading scientists and journalists. He also worked for Science for long enough to know “who the fools are over there”, as he recently put it. So we asked him what he made of the journal’s role in hyping the GM rice study.

“Science has some great reporters,” he told us. “I know that because I worked with them for 25 years. But the journal has shown itself to be way too credulous when it comes to certain politically charged areas of science, such as GMO research and Covid origins. In those areas, its reporters all too often give deference to establishment views and fail to follow up when those views are challenged by other scientists with differing perspectives and, as in this case, facts that challenge the mainstream narrative. That failure to follow up has to be laid mostly at the feet of the journal’s editors, whose conservative, establishment approach does not serve readers well.”

Between the credulity of journal editors and the uncritical approach of much of the media, the potential of crop genetic engineering is artificially inflated way beyond what it is actually capable of delivering, at the expense of proven effective and already available solutions.