Evidence presented in webinar shows Bt cotton has failed to deliver on yields and pest protection, concludes agroecology is the way forward. Report: Claire Robinson

An international panel of scientists who spoke in a webinar on genetically modified (GM) Bt cotton in India on 24 August presented evidence to show that the technology is ill-suited to Indian conditions and has failed to deliver on its promises. The webinar, organised by the Centre for Sustainable Agriculture and Jatan, a non-profit trust promoting organic farming, provides an evidence-based evaluation of 18 years of approved Bt cotton cultivation in India.

The speakers were Dr Andrew Paul Gutierrez, Senior Emeritus Professor in the College of Natural Resources at the University of California at Berkeley in USA; Dr Keshav Kranthi, former Director of Central Institute for Cotton Research in India; Dr Peter Kenmore, former FAO Representative in India; and Dr Hans Herren, World Food Prize Laureate. Dr Kranthi and Drs Gutierrez, Herren and Kenmore have all published studies on the performance and long-term impacts of Bt cotton. Their presentations benefited from detailed analysis of independently generated and published data gathered over the entire history of the crop.

Bt cotton “an aging pest control technology”

Speaking in the webinar, Dr Peter Kenmore called Bt cotton “an aging pest control technology”. He said, “It follows the same path worn down by generations of insecticide molecules from arsenic to DDT to BHC to endosulfan to monocrotophos to carbaryl to imidacloprid.” While corporate and public policy actors claim yield increases for chemical insecticides and Bt cotton, both technologies in reality “have delivered no more than temporary pest suppression, secondary pest release and pest resistance”.

As a result of these pest outbreaks, Dr Kenmore said, “Recurrent cycles of crises sparked citizens’ public action and sprouted ecological field research by committed scientists. When this research is taken on by farmers’ groups, they create locally adapted agroecological strategies. Their agroecology now gathers global support from citizens’ groups, governments, and UN-FAO. Their robust local solutions in Indian cotton do not require any new molecules, including endotoxins [toxins in bacterial cells] like in Bt cotton,” he said.

Bt cotton is the first and only GM crop that has been approved in India. It has been cultivated in India for more than 20 years, first illegally then legally. Political leaders and technocrats are often heard to be presenting a positive, hyped-up picture of Bt cotton in India. But on the ground, farmers are looking for other crops or non-Bt varieties of cotton to cultivate as an alternative to Bt cotton.

Insecticides cause pest outbreaks

Professor Andrew Paul Gutierrez, a leading quantitative cotton systems ecologist, focused on the ecological reasons as to why hybrid Bt cotton failed in India.

Prof Gutierrez pointed out that India could have easily learnt from the mistakes that happened in California in the 1960s and 70s, where pest outbreaks were mainly insecticide-induced. The pest explosions occur as a result of the natural insect predators of the primary target pest being killed off by the chemical insecticides or the Bt insecticidal toxins contained in Bt cotton. This phenomenon has been observed time and time again in countries across the globe. The cause was systematically explained in a book by Prof Robert van den Bosch, The Pesticide Conspiracy, published in 1978. Prof van den Bosch noted the pest explosions that always occurred after spraying.

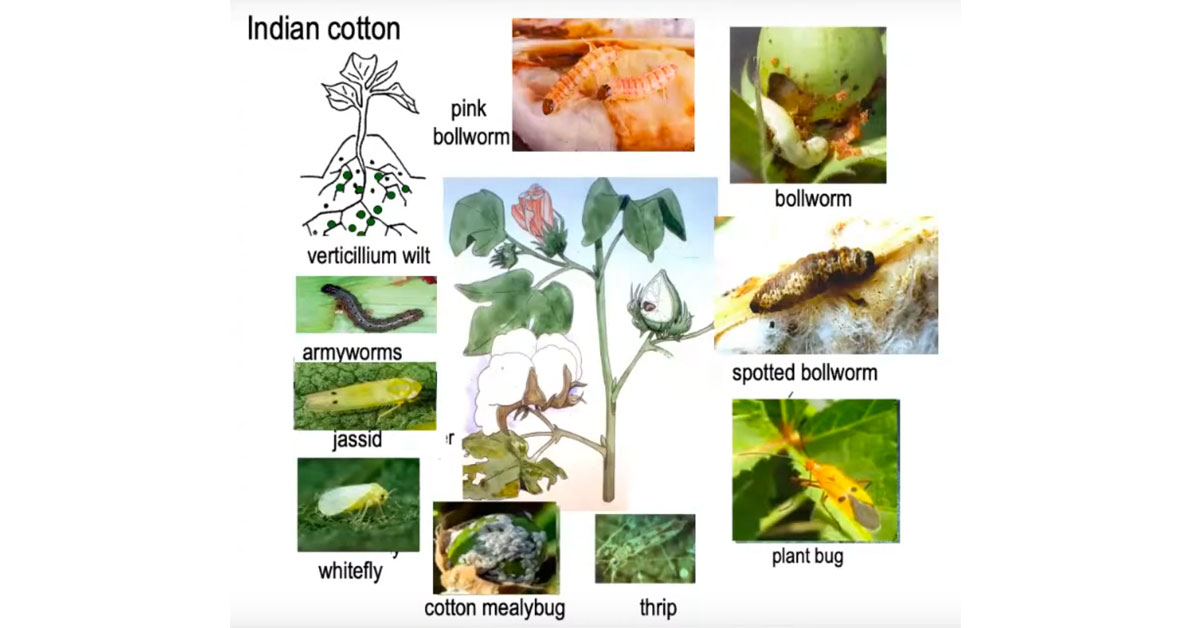

Prof Gutierrez said that with Bt cotton cultivation, pests that are normally rare exploded as their natural enemies were killed and the pest populations were able to move into the vacuum left. The main pest of cotton in India used to be the lygus bug, but when insecticide use became common, the bollworm emerged as the major pest – and was far more destructive than the lygus bug had ever been.

In reality, the lygus bug caused almost no damage to cotton. A study that Prof Gutierrez had been involved in (Gutierrez, Falcon et al 1975) showed that lygus bug was really not a pest at all and that yields in untreated control cotton were higher than yields in insecticide-treated cotton. Thus farmers, in buying insecticides, were “spending money to lose money”.

GMO and pesticide treadmills

Prof Gutierrez said that the long-season Bt cotton introduced in India was incorporated into hybrids that trapped farmers on biotech and insecticide treadmills. Long-season hybrid cotton is prone to bollworm attack. Insecticide use initially decreased after the introduction of Bt cotton, but this trend reversed from 2006, when yield plateaued and insecticide use began to increase once more. By 2013 insecticide use was higher than 2002 levels, the year before Bt cotton was legally introduced into India.

He explained, “The cultivation of long-season hybrid Bt cotton in rainfed areas is unique to India. It is a value capture mechanism that does not contribute to yield, is a major contributor to low yield stagnation, and contributes to increasing production costs.”

He said that the resulting economic distress led to farmer suicides. According to Prof Gutierrez, the solution is “adoption of improved non-GM high-density short-season fertile cotton varieties”.

Bt cotton has not provided higher yields or lower insecticide use

Dr Keshav Kranthi of the International Cotton Advisory Committee (ICAC) presented data on yields, insecticide usage, irrigation, fertiliser usage, and pest incidence and resistance. He said, “A critical analysis of official statistics shows that despite increase in area from 11.5% in 2005 and 37.8% in 2006 to a near saturation point after 2011, Bt hybrid technology has not provided any tangible benefits in India in the past 15 years, either in yield or insecticide usage.

“Cotton yields are the lowest in the world in Maharashtra, for example, despite being saturated with Bt hybrids and having the highest usage of fertilisers. Cotton yields of Maharashtra are less than in rainfed Africa, where there is hardly any usage of technologies such as Bt or hybrids or fertilisers or pesticides or irrigation.

“Indian cotton yields rank 36th in the world and have been stagnant in the past 15 years and insecticide usage has been constantly increasing after 2005 despite an increase in area under Bt cotton.

“Research also shows that the Bt hybrid technology has failed the test of sustainability with resistance in pink bollworm to Bt cotton, increasing sucking pest infestation, increasing trend in insecticide and fertiliser usage, and increasing costs and negative net returns in 2014 and 2015.”

GMOs: A technology searching for an application

Dr Hans Herren is an entomologist with an MSc in agronomy and plant breeding and a PhD in biological control. He led a successful biological pest management campaign in Africa that averted a major food crisis that could have claimed an estimated 20 million lives. He has also managed international agriculture and bioscience research organizations, as well as playing a leading role in global scientific assessments and policy processes.

In the webinar Dr Herren said, “GMOs exemplify the case of a technology searching for an application. To modify the genome of plants and animals serves only the short-term drive for profit at the cost of farmers, consumers and food security in the medium and long term. The technology is about treating symptoms, rather than dealing with the problem's root causes, i.e., taking a systems approach to create resilient, productive and biodiverse food systems in the widest sense and to provide sustainable and affordable solutions in the social, environmental and economic dimensions.

“Failure of Bt cotton is not just a failure of a product or the technology behind it, it is a classic representation of what unsound science of plant protection and faulty direction of agricultural development can lead to. Bt hybrid technology in India represents an error-driven policy that has led to the denial and non-implementation of the real solutions for the revival of cotton in India, which lie in HDSS (High Density Short Season) planting of Non-Bt/[non-]GMO cotton, in pure line varieties of our native Desi species and American cotton species.”

The only way to sustainability: Agroecology

Dr Herren said, “The only way we as members of the earth system will survive and also be able to meet our SDG [sustainable development goal] targets, is by transforming agriculture and the food system to agroecology, which includes regenerative, organic, biodynamic, permaculture, and natural farming practices.

“We need to push aside the vested interests blocking the transformation with the baseless arguments of ‘the world needs more food’ and design and implement policies that are forward looking, deal with the climate crisis, and help heal the COVID-19 pandemic aftermath. We have all the needed scientific and practical evidence that the agroecological approaches to food and nutrition security work successfully.”

There are numerous genetically modified food crops in the pipeline of approval and experimentation in India and those at the head of the queue waiting for regulatory clearance for commercial cultivation include a new Bt brinjal event (other than Mahyco’s Bt brinjal EE-1), Delhi University’s herbicide tolerant GM mustard, and Monsanto’s herbicide-tolerant and Bt GM maize.

The International webinar was organised by Centre for Sustainable Agriculture and Jatan in collaboration with Alliance for Sustainable & Holistic Agriculture (ASHA) and India For Safe Food. Participating in the webinar were hundreds of scientists from all over the world, in addition to farmers and other citizens.

In August, three of the experts cited above wrote an open letter to members of two influential Indian think tanks, rebutting their claims that Bt cotton in India has been a success.

Image: Pests and diseases of Indian cotton, problems of which have been exacerbated by chemical insecticide and GM Bt cotton use. From the presentation of Prof Gutierrez.