Study finds CRISPR/Cas gene editing causes “chromatin fatigue” – another surprise mechanism by which it can produce unwanted changes in gene function. Report: Claire Robinson and Prof Michael Antoniou

Study finds CRISPR/Cas gene editing causes “chromatin fatigue” – another surprise mechanism by which it can produce unwanted changes in gene function. Report: Claire Robinson and Prof Michael Antoniou

CRISPR/Cas gene-editing unintentionally disrupts multiple gene functions in a way that is passed to successive cell generations, a recently published scientific study shows. The disruption followed repair of a DNA double-strand break at the intended gene edit sites.

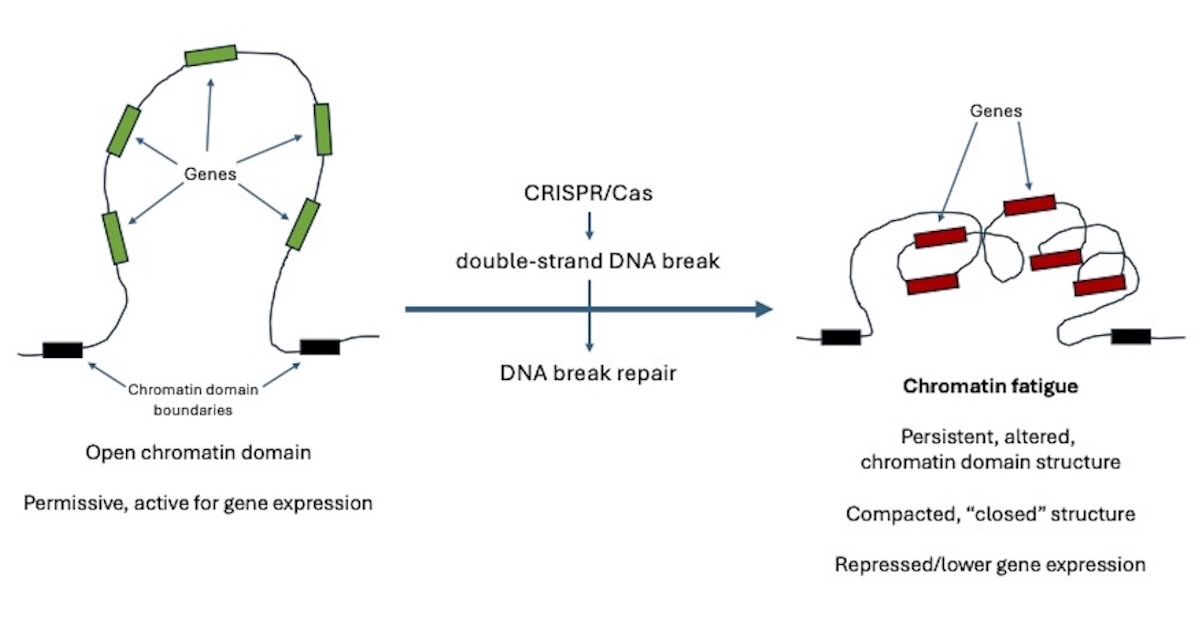

Cells organise their DNA in a three-dimensional structure (called chromatin) that is crucially involved in the control of which genes are turned on or off. The authors of the new study, who are based in Denmark, investigated whether chromatin structure fully recovers after DNA damage is repaired. Using CRISPR/Cas gene editing, the researchers introduced targeted DNA breaks (the necessary and universal first step in the gene editing process) and then tracked changes in genome (chromatin) organisation and gene activity. They found that even after the DNA was repaired, the chromatin of the affected regions remained misfolded and showed reduced expression of multiple genes, and these changes were passed on to daughter cells. DNA damage therefore leaves lasting marks on genome expression.

The authors, Susanne Bantele et al, call this phenomenon “chromatin fatigue”. They note that it is a hitherto unknown effect of cells’ responses to DNA breakage and repair, with the potential to permanently alter the makeup and functioning of gene-edited cells. That includes apparently “successfully” edited cells and their successive daughter cells.

This type of effect, which does not alter the DNA sequence but alters gene expression – the way that genetic information is utilised – is called an epigenetic (“above the genes”) effect.

Implications of the study

The study was carried out in human cells and the authors are solely concerned with gene editing used within a human gene therapy or experimental context. However, the effects found, in all likelihood, will also occur in plants and animals. This is because plants and animals share the same gene and chromatin structure and associated regulatory genetic processes. The findings have serious implications for the safety and performance of these organisms – and therefore how they should be regulated. For example:

* In gene-edited plants, alterations in gene expression patterns could lead to altered biochemistry, including the production of novel toxins and allergens or higher levels of existing toxins and allergens, or altered nutritional value.

* In plants, the unintentionally altered gene expression caused by gene editing could carry through to the final marketed product – and potentially down through the generations if sufficient backcrossing with conventional plants is not done to try to remove the unwanted alterations.

* In gene-edited animals, the disruptions in gene expression following the DNA repair could trigger severe physiological consequences such as birth defects and cancer.

* In plants and animals, even in cases when the gene edit appears successful, the resulting organism must be subjected to in-depth molecular profiling and physiological analyses to check for unintended and potentially dangerous consequences.

* Investigations must be done to see whether the epigenetic phenomenon called “chromatin fatigue” is stably inherited, not only through successive cell generations, but also through future generations of the entire organism, through propagation.

The scientists’ discovery applies to all types of gene editing, whether SDN1 (gene disruption), SDN2 (gene modification via insertion of a repair template), or SDN3 (gene insertion). This is because all three types involve initially creating a double-strand break in the DNA and rely on the cell’s own repair process to bring the two broken ends of DNA together in a way that incorporates the intended gene “edit”.

The new findings provide compelling new evidence that moves to deregulate gene-edited organisms – or certain classes of them, such as SDN1 and SDN2 – are misguided and irresponsible.

As an observation tangential to this article, the findings suggest that patients who have been treated with approved CRISPR/Cas-based gene therapy for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia should be examined via transcriptomics analysis for unintended alterations in gene expression following DNA double-strand break repair and resulting chromatin fatigue.

What’s new in this study?

Previous evidence has shown that gene editing can cause DNA damage in the form of small and large deletions, insertions, and rearrangements (including chromothripsis: chromosome shattering and random rejoining) at off-target and on-target sites in the genome, which in turn can lead to unintentionally altered gene function, with consequences for health and the environment.

The new study adds yet another mechanism – chromatin fatigue – by which major disruptions in gene function can be caused by gene editing processes: the CRISPR gene editing-induced double strand DNA break and subsequent repair can seriously impair the expression of many genes.

Will gene editing get better and eliminate this risk?

Additional risks posed by chromatin fatigue remain even if gene editing technology advances to the point where the edit can be targeted precisely and the gene editing tool causes no off-target mutations (though this imagined scenario is a Holy Grail of genetic engineering that is highly unlikely ever to be realised). That’s because chromatin fatigue is an on-target effect, occurring within the chromatin domain around the targeted edit site as an inevitable result of the intended DNA repair. As such, it cannot be avoided by using “improved” gene editing techniques.

Why the effect occurs

Chromatin is organised in domains, each of which usually encompasses many genes. The structure of a chromatin domain can be either permissive or non-permissive for gene expression. So the function of any given gene or genes is determined by the nature of the chromatin domain they inhabit. The new study shows that in the gene editing process (double-strand DNA breakage and repair), the genetic engineer is not just changing the function of one or a few genes, but altering the function of many genes, due to disruption of the structure of the chromatin domain within which the target gene or genes are located. Some will be switched on, others off.

In this process, precision and predictability are blown away. And even when the gene editing-induced double-strand break in the DNA appears to be successfully repaired, the outcomes of the “edit” are unpredictable.

Doesn’t nature do it too?

The authors state in their paper that DNA double-strand breaks can be caused by environmental stresses as well as by gene editing – though they don’t demonstrate that; nor do they mention the types of stresses they mean. Further investigation reveals that the types of environmental stresses needed to produce double-strand DNA breaks would rarely occur in nature, if at all, and would only arise in extreme and potentially catastrophic circumstances. Examples are exposure to mutagenic chemicals – or ionising radiation from X-rays, nuclear accidents, or radioactive elements like uranium. While radioactive elements are found in nature, our exposures are generally low and subject to stringent protective regulations. The same goes for exposure to mutagenic chemicals.

An article in Nature Education explains the consequences of mutations (DNA damage) that may result from exposure to ionising radiation: “These [double-strand DNA] breaks are highly deleterious. In addition to interfering with transcription or replication, they can lead to chromosomal rearrangements, in which pieces of one chromosome become attached to another chromosome. Genes are disrupted in this process, leading to hybrid proteins or inappropriate activation of genes. [In animals, including humans,] A number of cancers are associated with such rearrangements.”

The Nature Education article also notes that on the positive side, such mutations can provide sources of useful genetic variation. But crucially, the author adds that these mutations will be selected for or against over evolutionary time, protecting living organisms and the environment from the spread of harmful traits.

That’s a point that GMWatch has also made regarding unwanted foreign DNA insertions from gene editing versus any foreign DNA insertions that may happen in nature. Gene-edited organisms would be released on a far larger scale and in a much shorter time frame than would happen with a naturally occurring gene expression-altered mutant. Therefore, genetically engineered gene-edited organisms developed and released en masse in agriculture and ecosystems don’t share the “evolutionary time” safeguard.

Mutagens used in mutagenesis breeding are not normal environmental stressors

Plants are deliberately exposed to mutagenic chemicals or radioactive sources in mutagenesis breeding. This is not a natural process. It is designed to create large numbers of mutations, including double-strand DNA breaks. The results, as any textbook on the topic will tell you, are vast numbers of deformed, infertile, and non-viable plants. If the breeder is lucky, one or two chance mutations may emerge that are useful and used for breeding on.

A rare “success” from past attempts at mutagenesis breeding is the dwarfing trait in barley. But on the whole, mutagenesis breeding has not proven successful in producing useful crop traits. Accordingly, since the 1990s, its use has massively declined, to negligible levels.

In short, there is a documented history of extreme abnormalities in plants subjected to mutagenesis breeding. In contrast, in conventional breeding and natural reproduction, extreme abnormalities are rarely seen. If that were not the case, plant and animal breeders could not do their jobs.

Therefore we cannot assume that the DNA double-strand breaks and ensuing chromatin fatigue that are routinely caused by gene editing can equally occur in conventional breeding as a result of exposure to normal environmental stresses. This conclusion is backed by scientific findings drawn from the peer-reviewed literature that gene editing is 1000-10,000 times more powerful a mutagen than chemical and radiation-based mutagenesis, which in turn is far more mutagenic than natural reproduction.

Taking the above into account, it seems obvious that chromatin fatigue from double-strand DNA breaks will not be nearly as prevalent in conventional breeding as it is in gene editing – if, indeed, it occurs at all under normal environmental conditions. Therefore, chromatin fatigue is just the latest unintended effect of gene editing that elevates the risk profile of “edited” organisms far above conventionally bred ones.

Wakeup call for deregulation lobby

The study’s findings are a wakeup call to GMO developers, politicians, and regulators who have convinced themselves that SDN1 gene editing only involves changing a single gene. In reality, “editing” a single gene can disrupt the functioning of many genes, and this disruption could realistically be carried through to the final marketed gene-edited plant or animal.

When responding to critics who point this out, GMO crop developers often claim that they will only select for further breeding those plants with the small gene edits that they want. However, the new findings show that those desired edits – however small they are and however precisely they are targeted – will likely be accompanied by large-scale unintended chromatin disruption that will affect the function of many genes. And those unintended disruptions could potentially persist into future generations of the organism – a possibility that needs to be investigated in further studies.

The findings make a nonsense of the EU Commission’s proposal to exempt gene-edited plants from risk assessment and labelling if they differ from the parent plant by less than 20 genetic modifications. Even if less than 20 are intended, the resulting changes to gene expression will be widespread and may be dangerous. The new study also knocks further holes in the UK government’s so-called “Precision Breeding Bill”, which exempts any gene-edited plant or animal that could theoretically arise from “traditional processes” – in other words, conventional breeding. As mentioned above, even if chromatin fatigue does arise in nature, its effects on the fitness of the organism will be selected for or against over evolutionary time, which is not the case with any “precision bred” GMO as defined by the bill.

Ironically, several of the authors of the new study are employees of Novo Nordisk Foundation Centre for Protein Research. Novo Nordisk, a company that focuses on medical applications of genetic engineering, and the Novo Nordisk Foundation are part of a group called the Novo-family, which is actively lobbying for the deregulation of GMOs. We recommend that the lobbyists read and take note of their scientists’ new findings.

Don’t look, don’t find

If a gene-edited plant looks acceptable and (as is usually the case) the developer fails to carry out the type of in-depth analyses that could spot disturbances in gene expression, they may not notice any hidden problems – for example, those that might affect the safety of the plant for consumption or the environment. These will remain in the final marketed product.

If they do notice problems, they can try to remove them with successive rounds of backcrossing with conventional plants. But this process is costly, time-consuming, and fraught with difficulties, as it risks also removing the desired trait. As a result, “genome cleaning” by backcrossing is generally not done thoroughly enough.

What needs to happen now?

This study intensifies the need – long emphasised by GMWatch and numerous scientists – to conduct multi-omics (in-depth molecular analyses) of all gene-edited organisms before they are marketed. The results should be submitted to regulators as part of the risk assessment. Transcriptomics would show unexpected changes in gene expression due to the gene editing process; proteomics would show changes in protein profile; and metabolomics would show changes in metabolism (biochemistry). The last two methods would reveal if new toxins or allergens had been created by the gene editing process, or if levels of existing toxins or allergens had been altered.

The failure, and indeed the reluctance of most GMO developers to conduct these analyses – and the failure of regulators to require them – may help explain why the history of new gene-edited GMOs thus far is characterised by early promise in the controlled conditions of the lab and greenhouse but subsequent failure in the field and marketplace. Gene-edited product developers ignore the science revealing an increasing array of large-scale unintended genetic damage and altered patterns of gene function at their peril, as these could not only lead to poor crop and animal performance, but also put health and environment at risk.

The new study:

Bantele S et al (2025). Repair of DNA double-strand breaks leaves heritable impairment to genome function. Science 390(6773). DOI: 10.1126/science.adk6662

https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.adk6662

The study is not open access, but the preprint can be read here:

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.08.29.555258v2

Image courtesy of Prof Michael Antoniou (copyright-free)