Unauthorised herbicide-tolerant cotton varieties circulate in Dhar district of Madhya Pradesh: Ambika Subash* reports

This May, during a visit to a seed and pesticide outlet in Kawathi village of Manawar tehsil [subdivision], Dhar district, Madhya Pradesh, I saw neatly stacked bottles of herbicide glyphosate. Often used for weed control, glyphosate is infamous for its perceived impacts of human and environmental health – the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies it as “probably carcinogenic to humans”, while studies believe it may contribute to soil microbial imbalances and emergence of herbicide-resistant “superweeds”. A conversation about glyphosate with the shop assistant led to the subject of herbicide-tolerant seeds. He showed me seed packets they had gotten from Gujarat, “Yugam 5G” and “Bahubali 4G”, saying they offer dual resistance to pink bollworm, a major pest of cotton, as well as glyphosate. The seeds were in high demand, he said. Our conversation was quickly interrupted by the shop owner, who admitted that the seeds were technically illegal to sell, and said that they were only for use on his fields.

The “technically illegal” point came up because the fact that the seeds promised resistance against pink bollworm and herbicide tolerance suggested they were genetically modified (GM), although the packets did not mention so. GM herbicide-tolerant cotton is not yet approved for commercial cultivation in India. The Union government has approved only two GM cotton varieties: Bollgard I (BG) I and BG II-developed by US-based Monsanto and marketed through its Indian joint venture, Mahyco-Monsanto Biotech Ltd. These are called Bt cotton varieties, as they are modified to include a gene from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis that resists pink bollworm.

Monsanto has developed а third-generation variant, BG II Roundup Ready Flex (BG II RRF), that shows pest resistance and herbicide tolerance. In 2015, Mahyco-Monsanto brought it to India for approval, but withdrew the application in 2016 after field trials, citing concerns on the government’s policies for technology sharing. In 2021, Germany’s Bayer, which acquired Monsanto, resubmitted the application. Its approval is pending with the Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee and other bodies.

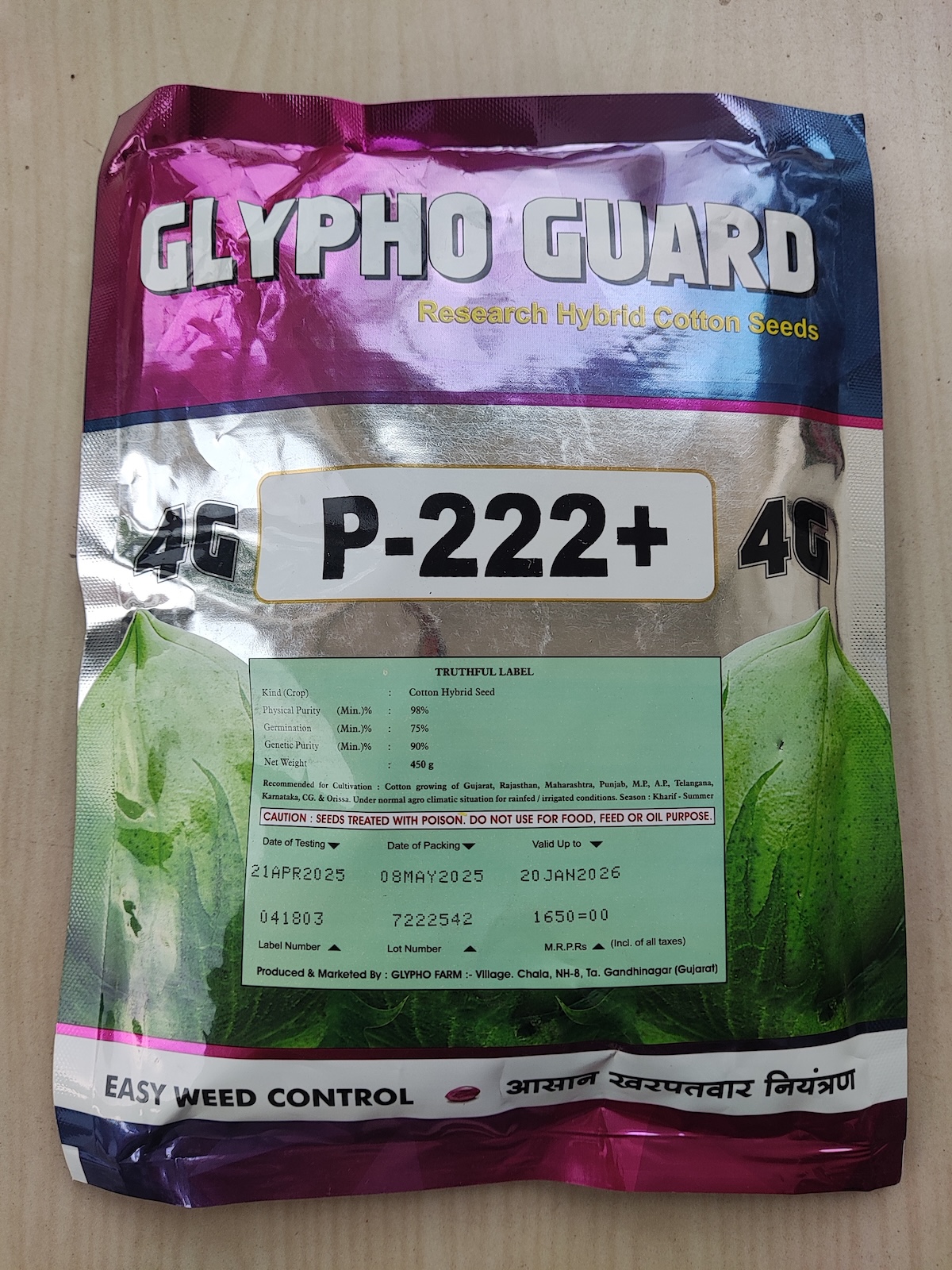

Yet herbicide-tolerant cotton seeds appear to be sold and used in not just Kawathi, but across villages in Dhar district. In Gangali village of Manawar tehsil, a farmer showed a group of other cultivators packets of “Glypho Guard 4G”, a glyphosate-tolerant Bt cotton variety he sourced from Gandhinagar through “personal connections”. He was optimistic about its cultivation and had already asked his relatives to start sowing it. When asked if the distributor mentioned on the packet, “Glypho Farms”, could be visited, the farmer said it may not even exist.

Media reports are highlighting such instances in not just Madhya Pradesh, but also Maharashtra and Gujarat. For instance, in early June, news reports said over 700 packets of unapproved Bt cotton seeds worth ₹15 lakh were seized from Maharashtra. The three states form India's largest cotton growing region, together accounting for about 56 per cent of the 12.37 million hectares of cotton acreage in 2022-23, says the “Agricultural Statistics at a Glance 2023” released by the Union Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare.

A clear choice

To understand the spread of herbicide-tolerant cotton seed varieties, I surveyed over 80 farmer households in five villages of Dhar district in May. All the respondents said they were aware that such varieties, known locally as “4G” or “5G” seeds, were likely illegal. Despite this, nearly half of them admitted to procuring them for use at least one season in the past five years, to avail the dual benefits of pest resistance and herbicide tolerance.

The names of the varieties shared were “Yugam 5G”, “Bahubali 4G”, “Glypho Guard 4G”, “Killer”, “Honey 4G”, “Rudra Plus”, “Rafel-1 4G”, “White Gold 5G” and “Nirbhay 4G”. When asked how they were made aware of the seeds, the respondents said that they were either informed by other cultivators, or were visited by “agents” of companies. Some said companies created a group chat on WhatsApp to share information. One respondent from Kawathi village mentioned that a company had taken 15 farmers of different villages on an “all expenses paid” trip to a farm in Gujarat to see the Rudra Plus seeds, though he did not divulge details about the trip.

The packets are sold for ₹1,500-2,100 per 450g, compared to ₹900-1,000 for BG II varieties like Rasi Seed's 659 and Nuziveedu Seeds’ Asha-1 (Ncs-866) that are widely sown in the region. In terms of procurement, the farmers said they would arrive by mail order from Gujarat. They did not share details of exact addresses.

In Katnera village in Kukshi tehsil, 30 farmers said that they had sourced three to five packets each of herbicide-tolerant Killer seeds in 2022. The seeds arrived in buses and were then distributed through local intermediaries, either directly to the farmers’ houses or at predetermined, isolated areas. Each packet cost around ₹1,500 and came without a receipt. I saw packets of the brand at a seed shop next to the village.

Discontent aids shift

Some 90 per cent of surveyed farmers said they sought new seeds because BG II – despite its reported resistance – saw recurrent attacks by pink bollworm and secondary pests like whitefly, aphids and thrips. In a focus group discussion held with 12 farmers in Kukshi tehsil, some said they sprayed up to 15 pesticides in one season to manage pest loads, and still saw yield loss. Some believed Bt cotton would be obsolete in three to four years, with “4G” and “5G” seeds taking over.

Local dealers note a dropping demand for the BG II seeds as well. In some cases, they have faced losses because they had to return more unsold packets than they anticipated.

High costs and labour shortage add to the challenges. Agricultural labourers in the cotton-growing regions of southern and western Madhya Pradesh often migrate seasonally to Gujarat, leading to labour scarcity during the peak weeding and harvesting months.

Women and children weeding a cotton field in Madhya Pradesh

With herbicide-tolerant Bt cotton seeds, farmers can directly spray glyphosate on the fields, reducing labour requirements for weeding.

This affinity for glyphosate is another point of concern, given its grave health concerns.

Agrochemicals for spraying cotton

Herbicides for sale during the cotton season

Regulatory gaps

Only a fraction of the farmers surveyed said they relied on government extension services for advice on seed selection. Most depended on seed dealers, private field agents and other farmers. In this vacuum, informal seed networks end up playing a dominant role.

Some larger cultivators – early adopters of herbicide-tolerant seeds – are reverting to BG II cotton or switching to soybean, maize or banana. For instance, in Katnera village, farmers said the Killer variety had a higher lint-to-seed ratio, which led to lower yield by weight per hectare compared to that of regular Bt cotton. This reduced “farm gate” prices, even though cotton mills approved of the variety's fibre quality. Many of these farmers returned to using BG II seeds.

The survey, as a whole, signals more than just isolated cases of unauthorised seed distribution. It exposes a weak regulatory regime, the retreat of public investment in agricultural research and development, and the near absence of credible agriculture extension services.

It is crucial now to resolve the regulatory lapses and to draft a national policy on GM crops, which must also address the widespread use and impacts of unapproved GM varieties. This was also highlighted by the Supreme Court in July 2024, during a case on GM mustard. The two-judge bench, while delivering a split verdict, directed the Centre to develop а National Policy on Genetically Modified Crops within four months – this is still pending.

Without such reform measures, illegal seed systems will quietly thrive and reshape agricultural innovation, as well as the relationship of farmers, technologies and the state.

* Ambika Subash (pictured below) is a PhD candidate in economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, researching the political economy of agricultural biotechnology.

This article was originally published by Down To Earth, India (Aug 1-Aug 15, 2025). It is republished by GMWatch with kind permission of the author and Down To Earth.

Photos: Ambika Subash