Even if you grow organic, your crops are at risk from contaminated animal manure. By Claire Robinson

Glyphosate is turning up in manure-based fertiliser used by gardeners and organic and conventional growers and the residues can ruin yields of tomatoes and other sensitive crops, new research from Finland shows.

The scientists were prompted to do the research based on an incident in Finland where a commercial tomato grower suspected poultry manure fertiliser of damaging their commercial organic tomato production. The grower company had commissioned testing, which revealed high levels of glyphosate residue in the poultry manure fertiliser they had used.

To test the possibility that the crop damage had been caused by the glyphosate residue, the scientists compared results from two manure-based fertilisers that were produced in Europe and marketed for professional horticultural use. The first ("G fertiliser") was the original fertiliser tested by the tomato grower and shown to contain glyphosate residue at a level of 0.94 mg/kg. The control fertiliser underwent similar testing and was found to have 0.23 mg/kg glyphosate.

As manure-based fertilisers, both products were marketed as suitable for use in certified organic crop production, but this does not mean the manure is from certified organic livestock.

To test the fertilisers, the scientists grew 72 Encore variety tomato plants for 14 weeks in a climate-controlled greenhouse according to the practices of the commercial grower.

The scientists found that the total harvest of tomatoes grown with the fertiliser with the higher level of glyphosate residue was 35% smaller, and the yield of first-class tomatoes 37% lower, than that of the control fertiliser with the lower glyphosate level.

In their paper, the scientists explain: “Except for the glyphosate content, the two fertilisers were substantively similar. Hence, the difference in tomato production between the two treatments can reasonably be attributed to the glyphosate residue present in a commercial fertiliser marketed (at the time) as suitable in certified organic horticultural production including for tomatoes.”

As part of the study, to ascertain awareness and potential contamination mitigation measures, the researchers contacted five fertiliser companies, two farming organisations, a feed company, and two government organisations working on nutrient cycling and agricultural circular economy.

Two of the five fertiliser companies identified poultry manure as a source of glyphosate contamination. Companies with awareness of pesticide residues reported interest in establishing parameters for pesticide residues.

Where does the glyphosate in poultry manure come from? While the authors of the paper do not address this question, two sources immediately come to mind: pre-harvest “desiccation” (dry-down) of feed grains by the spraying of glyphosate-based herbicides; and the spraying of these same herbicides onto GM glyphosate-tolerant corn and soy, which will be commonly used in poultry feed worldwide.

Bakery waste too toxic for fertiliser

A disturbing detail in the study is the finding by one fertiliser producer that herbicide residue in bakery waste is too high for fertiliser production – illustrating that regulatory limits on permitted pesticide residues in foodstuffs alone do not ensure that products can be safely recycled into the food system as fertiliser. If bakery waste is too toxic for plants, what effects are the bakery products having on humans who eat them?

Glyphosate residues have “negative impacts on crop production”

The authors conclude their paper: "The extent of glyphosate contamination of recycled fertilisers [i.e. manure or compost-based fertilisers] is unknown, but this study shows that such contamination occurs with negative impacts on crop production. Lack of testing and regulation to ensure that recycled fertilisers are free from harmful levels of glyphosate or other pesticides creates risks for agricultural producers. The issue is particularly acute for certified organic producers dependent on these products, but also for sustainable transitions away from mineral fertilisers in conventional farming."

Another pesticide industry-created headache

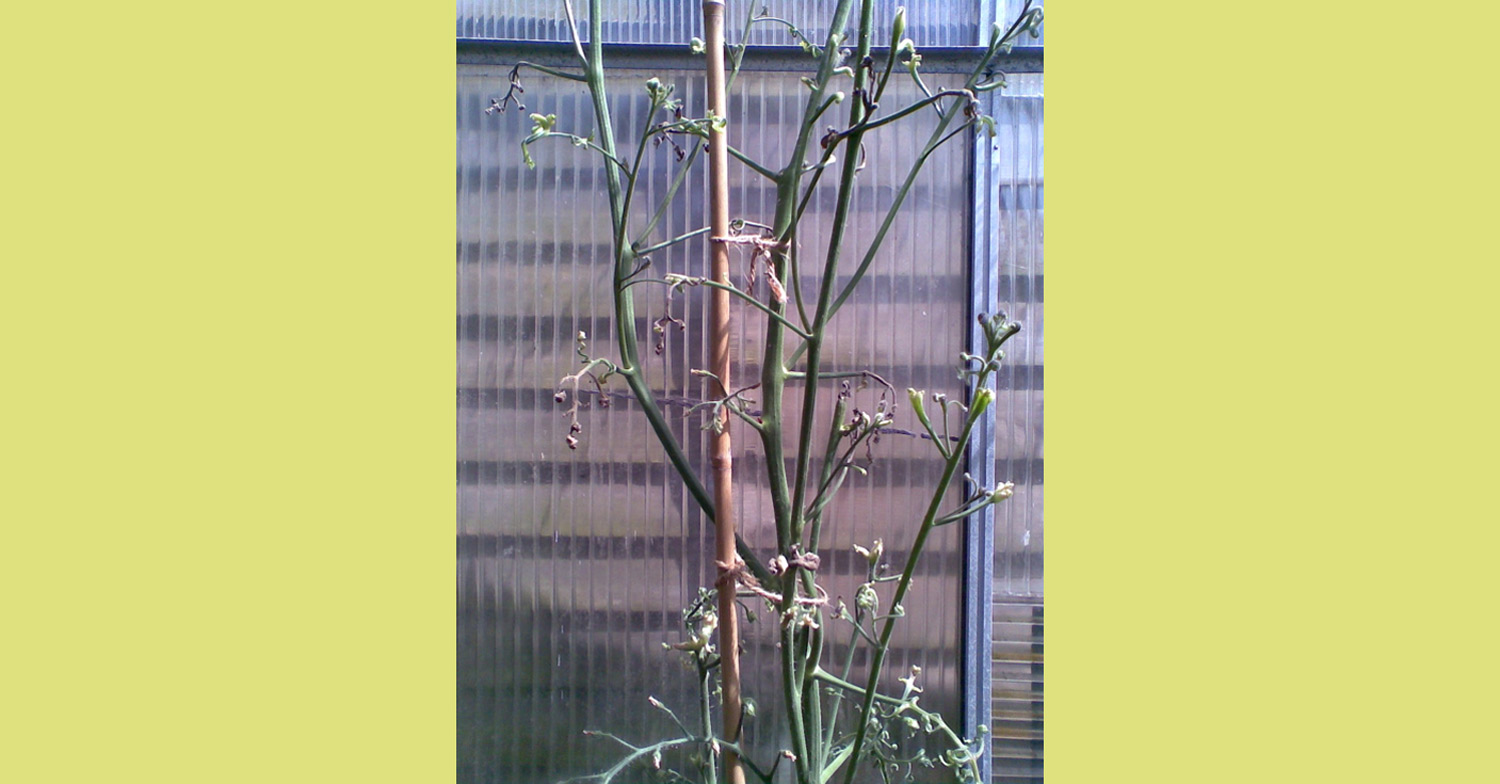

The research adds yet another pesticide industry-created headache to the longstanding one involving the herbicide aminopyralid, which regularly turns up in animal manure and is persistent enough to severely damage or kill plants grown with contaminated manure. Victims of aminopyralid damage include the author of this article and, very probably, the British author, broadcaster and vicar Peter Owen-Jones, who, on a quest to live a simple life in line with the principles of St Francis, found his home-grown tomato crop ruined by herbicide-contaminated horse manure (see around 13:34 minutes into the video linked).

On another scale of outrage altogether is the ongoing tragedy in the US of dicamba herbicide drift from dicamba-tolerant GM crop fields killing and damaging millions of acres of non-tolerant crops and wild plants, including trees.

These examples raise the question of how long society will be prepared to tolerate such chemical trespass and damage to our vital food crops. It also suggests that there is a commercial need for certified pesticide-residue-free or low-pesticide-residue fertilisers, with a premium paid to suppliers who guarantee that they have not used persistent agrotoxins in their production processes. It does, however, seem manifestly unfair that organic growers should have to pay that premium. A fairer system would be to force the polluters to pay via a tax on their pesticide products.

Top image of tomato plant affected by aminopyralid herbicide residue from contaminated manure, grown July 2008, Cheshire, UK. Note tightly curled leaves, which is a symptom of aminopyralid contamination. Image by Rhodian via Wikimedia Commons – public domain