Suddenly Jack Bobo is everywhere, with a position at the University of Nottingham apparently created for him. By Jonathan Matthews and Claire Robinson

A UK-based academic “has been named as the world’s leading expert on science communication”, according to the recent headline of an article that claims, “Professor Jack Bobo, Director of the Food Systems Institute at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom… has been recognized globally for his innovative work in science communication. Due to his prestige, it was recently announced that the World Food Prize Foundation in Iowa, United States will award him the Borlaug CAST Communication Award in October.”

What the article doesn’t say is that “the world’s leading expert on science communication” has also been dubbed “Mr GMOs” and has spent almost his entire career promoting the interests of the biotech industry. Nor does it say that the organisation (CAST) giving him that communication award has BASF, Bayer, Corteva, Syngenta and their agrochemical industry lobby CropLife America among its “sustaining members”, “grantors” and “event sponsors”. The article also fails to mention that previous recipients of the same award have included such controversial industry-linked GMO promoters as Kevin Folta, CS Prakash, Sarah Evanega and Alison Van Eenennaam.

Similarly, Jack Bobo’s billings as a speaker at the many UK and EU events he has been popping up at since taking up his position at Nottingham rarely provide insight into his real career trajectory. Prospective attendees at this year’s Low Carbon Agriculture Show at Stoneleigh in Warwickshire, for instance, were only told that in addition to being the Director of Nottingham’s Food Systems Institute, Bobo had “previously served as the Director of Global Food and Water Policy at The Nature Conservancy and as the CEO of Futurity”. And none of that gives any real sense of the man, his mission, or who Bobo has really served for the last quarter century.

Washington’s corridors of power

So who is Jack Bobo? In 2002, following a two year stint providing “legal analysis and research on a wide variety of issues related to the biotechnology and agriculture industries” for an international law firm advising multinational corporations, Jack Bobo took on the role that would make his name as one of the world’s leading GMO spin doctors.

As he told the US Congress in 2021: “I served for 12 years as the senior advisor for global biotechnology at the US Department of State under four secretaries and during two administrations... During that time, I traveled to approximately 50 countries meeting with ministers, parliaments, executives, scientists and students to discuss biotechnology policy and regulations. I also participated in and/or led numerous biotech trade negotiations. In 2015 I was recognized by Scientific American as one of the one hundred most influential people in biotechnology.”

Bobo’s notable degree of influence stemmed not just from his own gifts of advocacy and persuasion but, as we shall see, from his position as a senior official of a global superpower aggressively promoting biotechnology as a key US strategic interest.

Promoting the biotech industry’s agenda worldwide

An insight into just how high the promotion of GMO crops is on the US foreign policy agenda was provided by the publication – during Bobo’s time directing biotechnology trade policy there – of a trove of State Department cables, obtained by WikiLeaks. These showed the State Department using multiple resources, up to and including US ambassadors, to pressure foreign governments to adopt pro-GMO policies and laws and/or oppose safeguards and the labelling of GMO foods.

What emerges from the cables overall, to quote the food and farming researcher and writer Tom Philpott, is that “the US State Department has been essentially acting as a de facto global-marketing arm of the ag-biotech industry,” with its officials literally being instructed to “encourage the development and commercialization of ag-biotech products” while fighting tooth and nail to weaken regulation and prevent GMO labelling.

In addition, the leaked cables show, unsurprisingly, that this taxpayer-funded lobbying was closely coordinated with the industry it benefited. The State Department also worked closely with the US Trade Representative, as well as USAID and what is described in one leaked cable as “a host of other USG [US Government] agencies, international organisations, NGOs”. The same cable also noted that while the State Department had a whole section of staff “available as appropriate to advocate in host capitals, troubleshoot problematic legislation, and participate as public speakers on ag-biotech”, the GMO lobbying show had only one star: “In particular, this is the key role of the State Department’s Senior Advisor for Biotechnology, Jack Bobo.”

Bobo’s lead role in this global campaign is, according to a multi-award-winning French documentary, what led some to dub him “Mr GMOs”. And GMOs for Bobo and the US government, the film makes clear, “are like weapons or oil – a power asset.”

Man on a mission

Only a tiny number of Bobo’s own lobbying trips to “approximately 50 countries” actually feature in the cables leaked to Wikileaks – his missions to: Thailand, Hungary and Romania in 2009, and the Vatican in 2005. But these contain enough detail to give a flavour of Bobo’s lobbying, including how closely he coordinated with industry and how they colluded to overcome local democratic opposition.

The Hungary cable, for instance, reports how Bobo “proceeded to Budapest” following a Codex meeting (see below), “for briefings with FCS (Foreign Commercial Service, which helps US companies increase their sales) and American biotech firms Monsanto and Pioneer”. This was “followed by outreach meetings with the Ministry of Agriculture and the Parliament’s Agricultural Committee”. What was under discussion was Hungary’s GMO crop ban. Bobo’s Budapest visit was part of a “steady stream of carefully orchestrated outreach” that the cable says it is hoped “will eventually wear down Hungary’s resistance to lifting the biotech ban”.

Bobo’s mission to Bucharest the following week involved a more cooperative “pro-biotech” government that Bobo was eager to help push GMO crops both nationally and within the European Union. The cable recounts how a senior Romanian official expressed his “frustration” to Bobo that Romanian “government officials must advocate for agricultural biotechnology. In his opinion, private industry should better organize biotech supporters to ensure their voices lead public debate, not the government”. This, the official said, would enable the government to pose as a “mediator” rather than a GMO promoter, and so win more public trust. When Bobo subsequently met with “industry representatives from Monsanto and Syngenta” in Bucharest, they “agreed that organizing a group of pro-biotech supporters would be beneficial and could help support Romania”, among other countries.

The cables also expose even more direct US involvement in creating proxies in Romania. Specifically, they show how – in order to up the ante on a previous government that was less “pro-biotech” than the one Bobo encountered in 2009 – the State Department helped set up a pressure group to aggressively campaign for GMO crops, as another leaked cable explains: “the Biotech Farmers Association (BFA), a local non-governmental organization (NGO) established last fall with the assistance of the [US] Embassy, is actively lobbying GOR [Government of Romania] officials in support of GM soybeans. When asked what they would do if the GOR does not approve GM soybeans for 2006, one farmer told EconOff [the US consulate’s Economics Office] that they would plant anyway and create a political and legal crisis.”

“A nasty piece of work”

Underhand tactics also impacted the work of the Codex Committee on Food Labelling (CCFL), where Bobo led the US campaign to try and block the development of labelling guidelines for GMO food products. We gained some insight into this prolonged campaign of obstruction by Bobo’s team when we interviewed a US scientist and international expert who monitored CCFL’s work and had observer status at its meetings. He bluntly described Bobo to us as “a nasty piece of work” and gave us examples of the kind of arm twisting engaged in behind the scenes in the US effort to undermine support for the guidelines.

In his own case, for instance, the scientist was told he was “a traitor” for supporting GMO labelling. He said another observer with a good working knowledge of the local language of one of the African CCFL delegates had discovered in conversation that the US had threatened to cut off food aid to his country if he voted in favour of the labelling guidelines. It was also very noticeable, our source said, that the “postage stamp countries” (microstates) invariably lined up with the US when it came to voting, in a way that left little doubt that they had been leaned on. Thanks to such hardball tactics, it took nearly two decades before the CCFL finally managed to develop labelling guidelines that were approved.

Why were Bobo and his colleagues so determined to obstruct that process? The US had long threatened countries wishing to introduce GMO labelling, particularly mandatory labelling, with the prospect of a legal challenge at the World Trade Organisation. As Codex is internationally recognised as the relevant standard-setting organisation for food safety and labelling issues, the spectre of a WTO challenge for restricting trade became far less credible once GMO labelling was clearly allowable within Codex guidelines. In other words, approved guidelines could inhibit the US’s ability to use the WTO to force GMO foods onto unwilling consumers.

Spinning through the revolving door

After the obstructing of Codex ended in 2011, Bobo’s main job in his last few years with the State Department appears to have been much more public facing. According to Bobo, it mainly involved “just going round the world giving speeches” – hundreds of them, about why we need GMOs to ensure people are well fed, and how to build trust in the food system.

Having honed his communicative skills on this global speaking circuit, in July 2015 Bobo moved directly from serving as spin doctor in chief in the State Department’s marketing of “ag-biotech” to lobbying directly for a DC-based corporation trying to punt everything biotech, from GMO apples and GMO salmon to GMO mosquitoes, gene therapy and animal cloning.

A report in a German daily in 2016 captures Intrexon’s Chief Communications Officer in full evangelical mode: “Jack Bobo was on a mission when he entered the windowless meeting room in Washington. The message he delivered this spring was a simple one: only genetic engineering can heal the rift between agriculture and the environment. But this could only happen if people first began to accept genetic engineering. He believes that ‘the [GMO Arctic] apple is the product that may be able to sway consumers’.

“Bobo, however, is required to voice such opinions since he is a lobbyist for the US genetic engineering company ‘Intrexon’, which dabbles in medical supplies as well as agricultural solutions. His eyes light up while describing so-called ‘Arctic Apples,’ which are apples that do not oxidize when cut. They are also the first genetically modified apple of the ‘Granny Smith’ variety nearly ready for release, and its flesh is as white as the eternal ice of the Arctic.”

Three years later at a US Department of Agriculture outlook forum in Washington, Bobo was still singing from the same hymn sheet, as a leading Canadian farm publication reported: “Jack Bobo doesn’t hold back when talking about the Arctic Apple. He believes the non-browning apple could change how people think and talk about genetically modified food. ‘I like to say it’s the most important GMO in the history of the world.’”

Industry advocacy in Washington

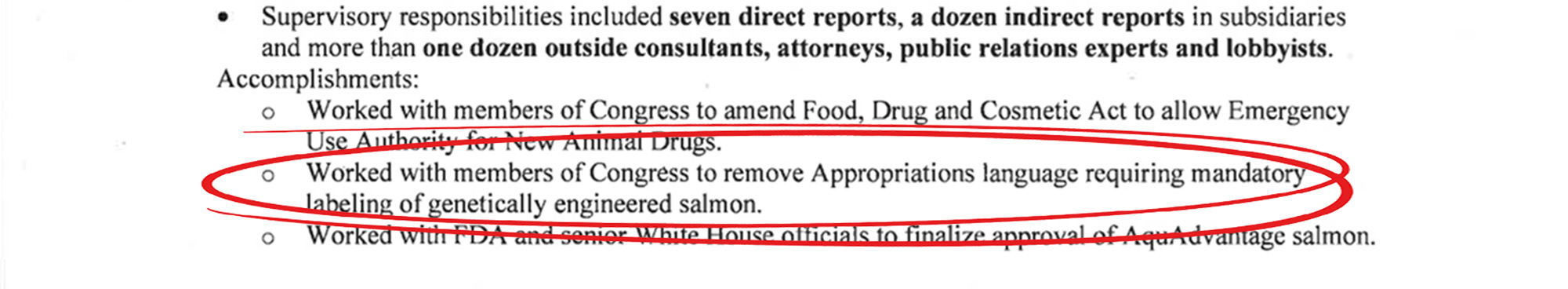

But Intrexon’s new spinmeister didn’t just earn his pay waxing lyrical about GMO Granny Smiths. As the company’s vice-president of global policy and government affairs, he also served on the board of its GMO salmon subsidiary, AquaBounty. And this is where his deep familiarity with Washington’s halls of power paid dividends.

While helping guide the development of the GMO fish firm at board level, Bobo also, according to a CV he submitted to Congress:

• Worked with members of Congress to amend Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act to allow Emergency Use Authority for New Animal Drugs [read: GMO animals like AquaBounty’s GMO salmon].

• Worked with members of Congress to remove Appropriations language requiring mandatory labeling of genetically engineered salmon.

• Worked with FDA and senior White House officials to finalize approval of [AquaBounty’s GMO] AquAdvantage salmon.

And as a result of the salmon approval, which critics panned as characterised by “sloppy science and deficient data”, AquaBounty’s GMO salmon finally hit the US market in June 2021. But by then, Bobo was long gone.

Leaving a sinking ship

The AquAdvantage salmon made little market impact and in the three years since its launch, despite ambitious expansion plans, AquaBounty has shown increasing signs of struggling financially. Nor did the commercial release of the Arctic apple do anything to transform the GMO debate, in spite of being “the most important GMO” ever. As for Intrexon itself, shortly after Bobo’s 2019 departure, it began offloading all its GMO subsidiaries – apples, salmon, mosquitoes, the lot.

The writing had been on the wall for a while. In 2018, Bloomberg warned that as the company’s GMO products had “failed to curry favor with investors”, Intrexon had become not just “a frequent target of short sellers” but “the most shorted name on the Bloomberg World Index”.

In fact, the simplest way to understand Intrexon’s parting of the ways with “Mr GMOs” and its various GMO subsidiaries is by tracking its stock price. Shortly after Bobo joined Intrexon, it had hit an all-time high, closing at $67.99 in August 2015. But by the time of his departure in April 2019 it had crashed below $5 and was showing no signs of breaking its fall.

Within a year Intrexon no longer existed, having changed its name to Precigen and morphed into a company focused solely on biopharmaceuticals. Jack Bobo had also had a relaunch – this time with the help of a far bigger corporation.

The future of food: “funded, in part, by Bayer”

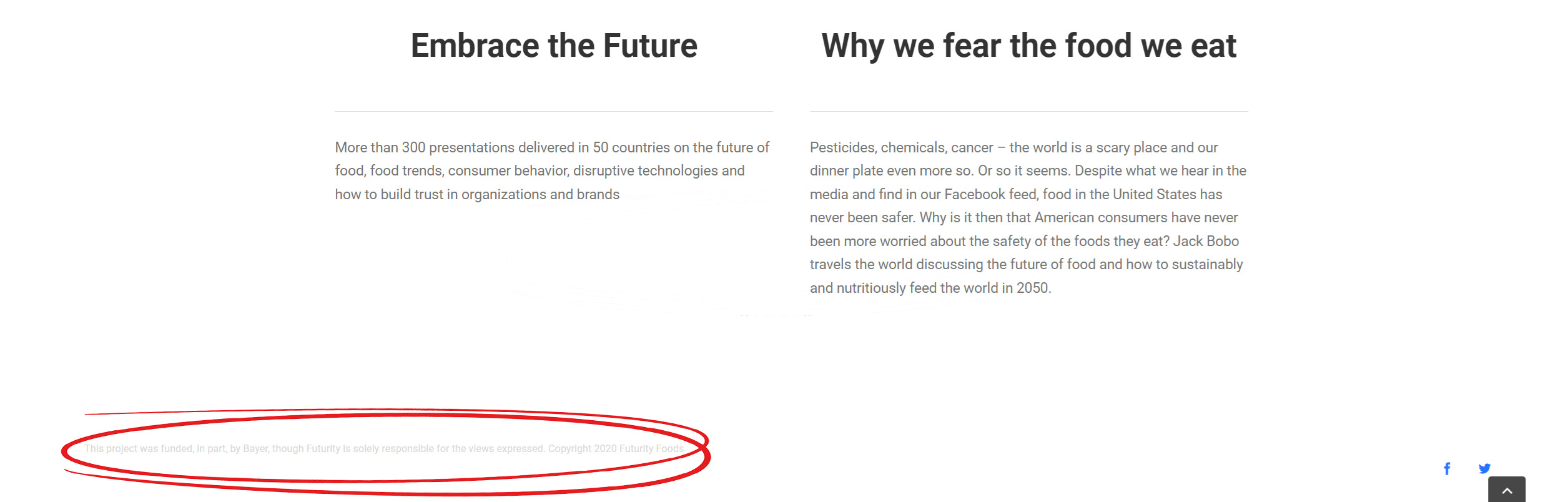

“I am Jack Bobo, CEO of Futurity, a food foresight company,” Bobo told a joint meeting in 2021 of two Congressional sub-committees that were looking into the future of biotechnology. The CV accompanying his testimony explained that Futurity “advises companies, foundations and governments on emerging food trends”.

Although the same document speaks of his “joining” Futurity, we could find no evidence of the company existing independently of him. The company’s website futurityfood.com, for instance, appears to be a vehicle almost solely for promoting Jack Bobo in his latest spin-doctor incarnation as a consultant, a course provider, and speaker-for-hire, and more generally as a “food futurist” and “global thought leader” helping firms stay ahead of future food trends.

Interestingly, although there are multiple references to consumer psychology – Bobo has a BA in psychology and chemistry, the word “GMOs” appears almost nowhere on the site, and Futurity provides no details of which “companies, foundations and governments” it works with. But tucked away down at the bottom of each page of futurityfood.com is the following small-print message in the faintest of greyscale: “This project was funded, in part, by Bayer, though Futurity is solely responsible for the views expressed. Copyright 2020 Futurity Foods”.

Champion of transparency

As a hugely experienced speaker-for-hire, Bobo found no shortage of takers, even at $10,000-$15,000 a pop plus expenses. But when the CEO of Futurity was flown to a New Zealand Wine conference, one wine producer angrily demanded to know why New Zealand Wine was “spending significant money to fly a GMO spin doctor from the United States to GM Free Hawke’s Bay to take centre stage at the annual conference, providing a free platform for him to promote GMOs”.

There were also serious questions about how much anyone could trust what the “GMO spin doctor” had to say. When Bobo had been at a biotech conference in New Zealand three years earlier, while still lobbying for Intrexon, the local media had reported his pitch as “you can’t have [consumer] trust without transparency”. His keynote address even generated the headline: Intrexon says transparency on GM will win over public.

Few readers would have guessed that this champion of transparency had until recently been a key player in the State Department’s campaign of aggressive opposition to GMO labelling in countries around the world, let alone that he had been heavily involved in obstructing approval of labelling guidelines at Codex.

With equal shamelessness, four years later when CEO of Futurity, Bobo told the technology reporter Antonio Regalado regarding labelling AquaBounty’s salmon, “it’s best to be transparent and hope that people don’t really care [that it’s GMO]”. Yet nine months later on the 2021 CV that he submitted to Congress, Futurity’s CEO would list under “Accomplishments” his work with members of Congress on removing the requirement for “mandatory labeling of genetically engineered salmon”. That work on keeping consumers in the dark was almost certainly undertaken after promoting the message “you can’t have trust without transparency”.

Big Green Bobo

In 2022, Bobo took on the first of two incarnations that seemed to seriously distance him from marketing, advising or otherwise working for the biotech industry. But the first of these gigs, working for a US environmental group, was nowhere near the radical departure it appeared.

That’s because his new employer, the Nature Conservancy (TNC), is a multibillion-dollar green goliath, long wracked by scandal and controversy, and well known for not just accepting money from environmental destroyers, including millions from Monsanto, but for giving them a say in how it is run.

Corporate influence flows both through TNC’s board, on which the likes of Dow Chemical’s former Chairman and CEO, Michael Liveris, has sat alongside investment bankers and other corporate bigwigs, and via its Business Council, which has included a long list of hugely controversial corporations, such as BP, 3M, Cargill, Chevron, Shell, Dow Chemical and – once again – Monsanto.

TNC has even turned to Monsanto for staffing, including Monsanto’s Michael Doane, who, after 16 years with the corporation in “a variety of roles in sales, product development and industry relations”, including trying unsuccessfully to launch Roundup Ready Wheat onto the market, was appointed TNC’s Global Managing Director for Food and Freshwater Systems in 2019. It’s in this context that in 2022 Jack Bobo was appointed to work with Doane, among others, as TNC’s Director of Global Food and Water Policy.

Putting the stain in sustainability

TNC’s close collaboration with big business has been described as “trusting the main forces behind ecological ruin to reverse it”. And in her scathing 2005 article, The stain in sustainability, Sharon Beder not only tore into TNC for acting like a front for corporate business, but exposed the way the language of “sustainable development” was providing cover for what organisations like TNC were getting up to.

The Australian engineer turned academic – probably best known for her book Global Spin: The Corporate Assault on Environmentalism – explained how sustainability was being spun to turn technology and industry from causes of environmental destruction into the ones “expected to provide the solutions to environmental problems”. This served to justify environmentalists and businesspeople working together, as “Sustainable development seeks ‘win-win’ solutions to environmental problems that do not interfere unduly with business activity”.

Seventeen years later, when Bobo was interviewed about his role at TNC, he deployed exactly this line of spin to make agribusiness, and in particular technology and “innovation,” appear as the keys to “sustainable agriculture”. “A lot of it has to do with how we frame the conversation,” he told his interviewer. The problem, Bobo said, is that conservation groups have tended to lead with the damage intensive agriculture does to the environment – its impact on land and water, its major contribution to climate change. But, he said, it should be framed instead in a way that emphasised that “advances in agriculture” were the key to feeding the world without destroying even more of nature.

“The best way to ensure conservation is to ensure that people are well fed,” because then they won’t want to remove areas of nature to produce food. That meant, Bobo explained, that his job at TNC in relation to international treaties, for example, was balancing the conservation goals with encouraging recognition of the importance of not obstructing agriculture, i.e. intensive high-input agriculture, from keeping people fed and creating a sustainable future.

Bobo paints a simplistic picture in which, although farming with “fewer inputs” may cause less damage locally, it inevitably equals “less (food) output,” which “means somebody else has to make up the difference”. Intensive agriculture, on the other hand, is “highly productive” and so conserves land globally. Thus, “When we farm more intensely in the United States, there’s less deforestation in Brazil”. Meanwhile, technology and innovation hold out the promise of making intensive farming less environmentally damaging locally too, providing a win-win solution.

But in reality, the type of environmentally damaging industrial agriculture Bobo talks up actually feeds a surprisingly small proportion of the global population. Meanwhile, as Miguel Altieri, the former General Coordinator of the United Nations Sustainable Agriculture Program, points out, low intensity agroecological farms can conserve biodiversity, restore soil fertility, and maintain crop yields under conditions of environmental and climatic stress. Indeed, most agroecological farms, Altieri says, can actually “outperform industrial agriculture in terms of total production”, as well as resilience, energy efficiency, and water use – so providing real win-wins.

And it isn’t just Altieri pointing this out. As far back as 2008, a prestigious report written by over 400 scientists and sponsored by the UN, among other major organisations, concluded that the key to sustainable long-term food security lies in agroecology, not GMOs.

Needless to say, none of that makes it into how “Mr GMOs” frames the conversation.

From Big Green to academe

While Bobo has lobbied for GMOs all over the world, his employers – whether law firm, biotech corporation, State Department or TNC – have invariably been headquartered inside the Beltway, the interstate highway encircling the US capital. Or at least that was the case until last year, when Bobo became the Director of the University of Nottingham’s new Food Systems Institute – a position that was apparently created especially for him.

Although Bobo’s admirers have hailed him as not just “the world’s leading expert on science communication” but a “renowned international scholar”, in reality his career has principally been spent advocating and consulting for industry and has involved no academic positions of any sort. Also, although the newly-minted “Professor Bobo” has several degrees, there are no science ones above undergraduate level, bar an MSc in environmental science. And the US scientist who encountered Bobo at Codex told us this lack of serious scientific expertise clearly showed whenever biotech issues needed discussing in any depth.

So why has Nottingham gone to the trouble of creating this director’s post specially for him? The answer may be provided by the Food Systems Institute’s “Future Proteins Hub”. The Hub website lists Bobo as one of its “experts” and says, “Our vision is to see a new protein economy by 2050”. Among the “major sources of protein” the Hub will be focussing on to realise its vision are “single organisms” (read: bacteria, or other single-celled organisms, genetically engineered to excrete proteins via synthetic biology) and “cultivated meat” (read: lab-grown meat).

Clearly, Bobo’s BSc in biology provides him with no credible expertise in regard to these or any other alternative proteins, but he has been involved in advising the lab-grown meat sector on issues like whether their product is best promoted to consumers as “clean meat” or “craft meat” – Bobo’s preference is for “craft” because it “evokes craft breweries and hand-jarred pickles”. And this surely explains Bobo’s relevant expertise and appeal. Nottingham wants a spin doctor to market the new institute and its output, not to mention provide “high-level advice to policymakers working on food, agriculture and other related issues”. And in that regard, Bobo really does have a noteworthy CV. He’s been enthusiastically pushing the interests of the biotech industry and related food and agriculture businesses for most of his career and on an international stage, and he is an impressively networked, experienced, and polished “influencer” as a result.

Boosting Bobo’s influence

Nottingham aren’t the only ones to appreciate Bobo’s merits in this regard, particularly now that this American biotech evangelist can be packaged as a UK university-based expert. This surely explains the recent lining up of Bobo for the Borlaug CAST Communication Award and the paeans of praise to his scholastic renown and global prestige.

And it doesn’t hurt that Bobo seems ready to clamber onto almost any available public platform. Among a whole flurry of recent gigs, he spoke at one session and chaired the other at a Westminster Forum event on the future of GMO gene-edited foods in the UK. These events, which are said to be aimed at policymakers, claim to provide “impartially-framed, inclusive discussion”. Yet that wasn't at all the case at this event, with only one obviously critical voice among a long line-up of speakers that essentially provided a pro-GMO chorus. But this partisanship was far less apparent in the case of Bobo’s university billing than that of, say, Bayer Crop Science’s Corporate Engagement Leader, even though both had spent much of their careers lobbying for GMOs.

A decade earlier, when he was still the senior adviser on biotech to Hillary Clinton, Bobo was once again in London, this time at a Chartered Institute of Marketing meeting on Food, Drink and Agriculture, where he is said to have “delivered a strong defence of GM crops in his lecture”. He apparently told his audience he “believes Europe’s opposition to GMs is wrong” and that “the EU moratorium on GM crops has been a disaster for trade”. He also “called on EU governments to follow the leadership” of the UK’s then environment minister, Owen Paterson – subsequently disgraced in a lobbying scandal – “and speak up about the benefits” of GMOs.

Bobo also reportedly said, “it will take a crisis to make everyone [in Europe] see the point of GM. There will be a move from not liking GM to requiring it”. As of 2024, such a crisis has not occurred, and if it had, there is no evidence that GMO crops could help solve it – though doubtless Bobo and the industry would have done their best to convince us otherwise.

What remains a mystery is why the UK and the EU would want to be advised on food and agriculture policy by an American lobbyist with such an obvious agenda and such a dubious track record.