International conference confirms detection of new GMOs is feasible for known/authorised products

Environment ministers meeting today in Brussels will discuss the EU Commission’s plans to deregulate crops produced with new GM techniques. The discussion coincides with an international conference on detection of new GMOs, the findings of which reveal that known and authorised new GMOs are detectable – thereby removing a reason that's often given for not regulating these GMOs.

At the Brussels meeting, environment ministers are expected to argue for keeping new GM crops regulated because of their potential impact on ecosystems. According to a report in Politico, "The skepticism towards NGTs [new genomic techniques] shared by several environment ministers contrasts with the views of their agriculture counterparts, many of whom argue that gene-editing technologies like CRISPR-Cas9 will deliver on their as-yet-unrealised promise to create climate- and pest-resistant super crops."

Ahead of today's talks, Austrian environment minister Leonore Gewessler, supported by Cyprus and Hungary, circulated a press release arguing that new GM crops should be subjected to stringent environmental and health safety checks.

The press release said of the Commission's proposal, "So far, the development of the draft law on risk assessment has relied only on questionnaires with predefined scenarios, through which the authorities of the member states are to assess the risks or even the market development of new genetic engineering."

Gewessler takes a critical view of this, stating, "In my view, legislation cannot and should not be developed on the basis of such vague assumptions. Particularly in the case of products that can have a wide range of effects on humans and the environment, a sufficient and balanced scientific basis must be the basis of any new regulation."

Gewessler is calling for sound criteria for a risk assessment of the corresponding products of new genetic engineering. And she calls for further discussions with experts to develop definitions and approaches that will then serve a practical application.

Gewessler said, "The Austrian position is clear: The three pillars of the precautionary principle, scientific risk assessment and mandatory labelling must also apply to new genetic engineering methods. New genetic engineering procedures through the back door are not acceptable to us. Consumers have the right to know what ends up on their plates."

For this reason, the Austrian delegation at today's Environment Council of the European Union in Brussels has called for an extraordinary agenda item on the topic. Gewessler already asked the EU Presidency in advance to set up an ad hoc working group to enable a broad discussion with all the disciplines concerned, such as environment, health and agriculture. Most recently, such working groups had already been successfully used in discussions on genetic engineering at the Council level.

Germany takes tough stand for strict regulation of new GM

Germany is also taking a strong stand in favour of strict regulation of new GM products. At an international conference in progress on "GMO analysis and new genomic techniques [NGTs]", which GMWatch is attending online, Germany’s deputy food and agriculture minister Silvia Bender said, "As of today, we are unable to identify NGT organisms unless we have the relevant sequence information. As a consequence of this, there have been calls for NGT organisms to be deregulated. I believe that this conclusion is too shortsighted and it doesn’t comply with my understanding of transparency."

Bender said it was crucial to retain "freedom of choice" for farmers, retailers and consumers and the “coexistence” of organic and conventional farming. She added that "the precautionary principle must take top priority without any reservations. This will be the only way to maintain the high safety level we have had so far."

Findings of conference on detection of new GMOs

In GMWatch's view, the conference that Silvia Bender speaks of has delivered the following take-home messages:

* As GMWatch has always said, if GMO developers provide regulators with the whole genetic sequence, good quality reference samples of the GMO and non-GMO comparators, and a validated detection method, most of which EU law currently requires for all GMOs,[1] there is no problem in detecting known and authorised new GMOs. That includes new GMOs with small gene edits, such as single nucleotide variations.

* Unknown/unauthorised GMOs can't yet be detected as there is no prior knowledge of the genetic sequence. But GMWatch points out that this has always been the case, even for certain older-style GMOs lacking the common elements that serve as "screening sequences", so new GMOs don't fundamentally change this situation. GMWatch is also aware that some scientists think that such unknown GMOs might be detectable in future, based on "scars and signatures" of genetic engineering, such as the FELIX project is working on.

* Detection methods for both known and unknown GMOs are being worked on by a number of laboratories across the EU and methods are improving all the time. The challenges, said one scientist, are "not insurmountable".

* Scientists recognise that the entire genome of new GM products, including both the intended and unintended changes caused by the genetic manipulation processes, must be taken into account in the detection and identification of new GMOs, in a so-called "matrix approach".

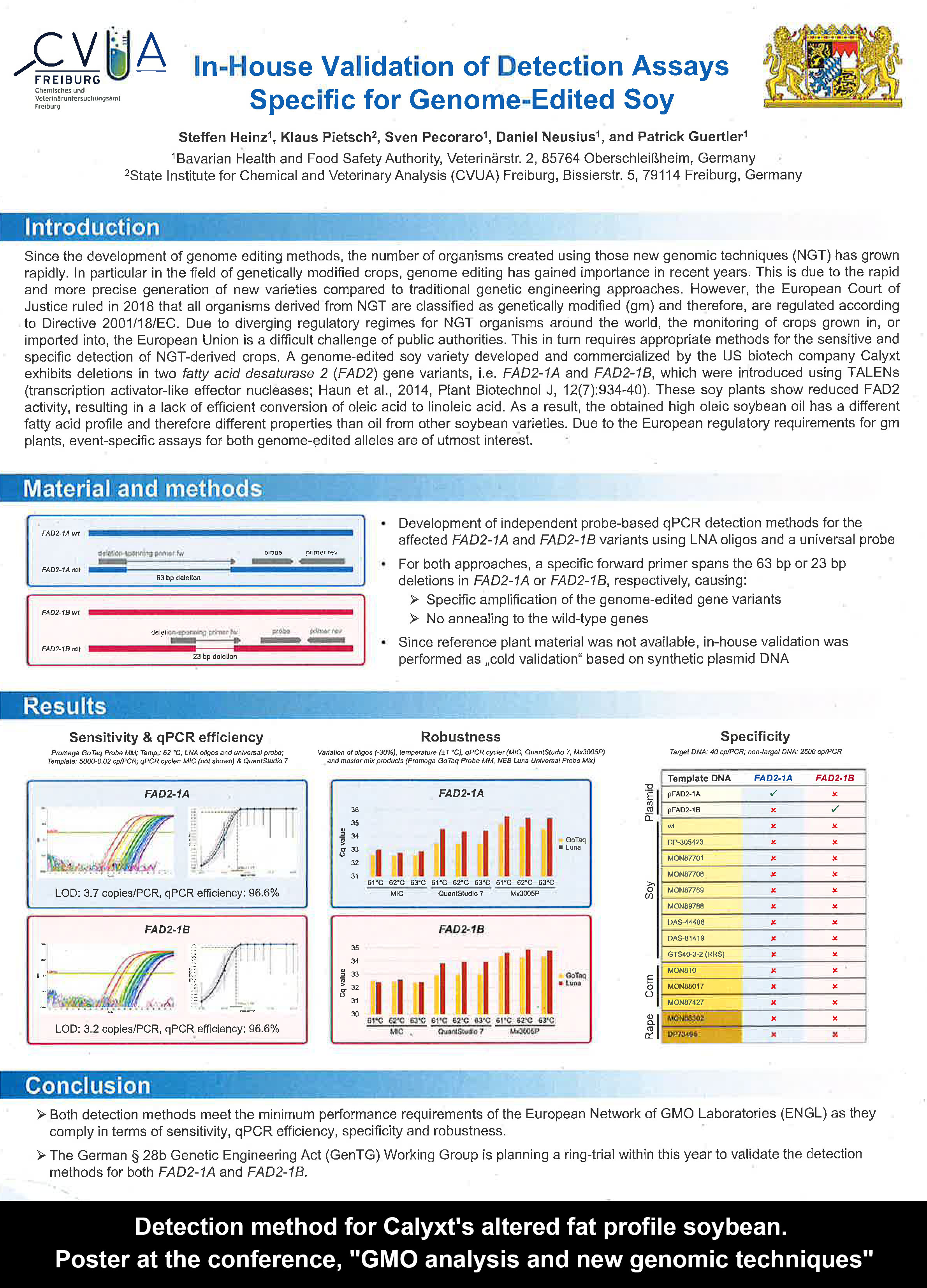

* The "matrix approach" can also include non-laboratory documentation enabling traceability, such as blockchain. * Validated (though not by the EU authorities, as far as we understand) detection methods for known commercialised gene-edited crops, including the Japanese GABA "sedative" tomato, Calyxt's altered fat profile soybean, Corteva's Waxy corn, and Cibus's SU canola, are already available.

* Validated (though not by the EU authorities, as far as we understand) detection methods for known commercialised gene-edited crops, including the Japanese GABA "sedative" tomato, Calyxt's altered fat profile soybean, Corteva's Waxy corn, and Cibus's SU canola, are already available.

* Detection methods cannot tell the difference between small deliberate mutations induced by gene editing and those mutations that are naturally arising or obtained from radiation- or chemical-induced mutagenesis. But GMWatch points out that detection methods, under EU law, have never been required to identify the GMO method used, so new GMOs do not change this fact.

* SDN-3 (gene insertion) gene-edited GMOs are very easily detectable as GMOs. However, most (90%) commercialised and in-the-pipeline new GMOs are of the SDN-1 (gene disruption) type and a few are of the SDN-2 (gene modification) type.

* A scientist from Corteva confirmed that the company's own detection methods can tell the difference between a gene-edited product and another with the same trait, produced through different methods.

* Scientists working on detection methods are hampered by the lack of information available in the public domain on which new GMOs are being developed and are already in the food and feed chains, the lack of information on genetic sequences, and the lack of reference sample material. The general belief is that currently there are not many such new GMOs circulating in the marketplace.

* Scientists want an international database of all new GMOs, both commercialised and in the pipeline, to be established. But they are not optimistic that this will happen any time soon or, if established, it would be comprehensive enough to include all new GMOs. Existing databases could be expanded to form such an international database.

* The main areas where unauthorised new GMOs are likely to be found are internationally traded commodity crops that are mixed together, e.g. soy, maize, and canola. "Small" crops such as the Japanese GABA tomato are not internationally traded and won't be found in the EU. Some new GMOs are designed for specific markets. The supply chain for those is controlled and identifiable in the interests of the developer, supplier, and client – for example, crops with altered nutritional profile.

Note

1. The only shortcoming in current EU law is that the whole genetic sequence is not required, just the sequence of the intended genetic change. In the case of new GMOs that would have to change to include the sequence of the whole genome.