By Beyond GM

For decades genetically engineered foods (GMOs) on sale in Britain have required a label. This label alerts consumers to the presence of genetically engineered organisms, allowing them to choose whether they wish to buy and eat such foods.

Labelling also allows producers and processors to decide if they want to produce foods containing GMOs.

In the UK, the responsibility for food labelling is split across several government departments and agencies.

The Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) Is responsible for food policy and general food labelling such as ingredients listings and country of origin labelling.

The Food Standards Agency (FSA) is responsible for policy on food safety, food hygiene (including allergens labelling), imported foods, novel foods and genetically modified foods. It is also responsible for other consumer interests in food, including price, availability and some aspects of food production standards like environmental concerns and animal welfare.

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) has responsibility for nutrition labelling as it appears on the front of food packaging.

Removing your right to know

Consumer surveys consistently show that the public wants genetically engineered foods to be labelled.

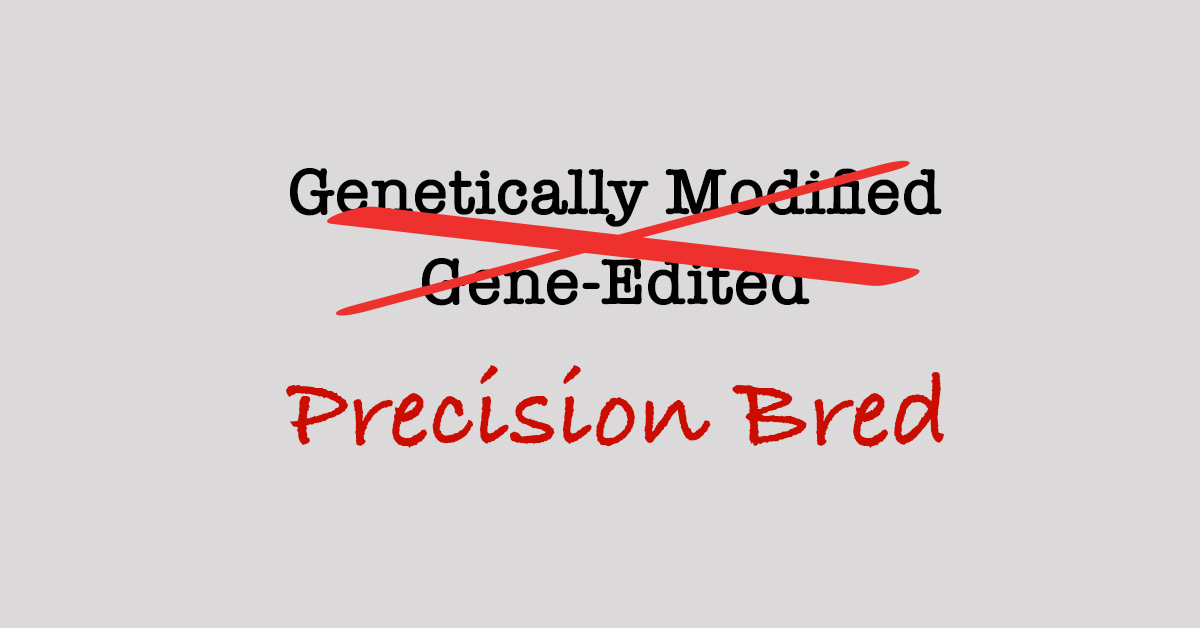

The draft Genetic Technology (Precision Breeding) Bill, currently before Parliament, removes all statutory requirements for labelling of GMOs. It does this by rebranding GMOs as “precision bred organisms”, or PBOs and redefining them as the products of “natural transformation” or “traditional breeding”.

Developers wishing to grow or place PBOs on the market will only need to self-certify that their organisms qualify for a regulatory, and therefore labelling, exemption.

Currently, the UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) has indicated that it intends to remove any labelling requirements for these genetically engineered foods and will also remove these foods from the novel foods register. With no statutory requirement for labelling and no apparent effort on the part of FSA to maintain and enforce labelling, we will no longer know what we are eating.

Precision bred = gene editing = GMO

How are our authorities getting away with this?

The abandonment of consumer labelling and rigorous traceability is rooted in the UK government and biotech research establishment’s false narrative that gene editing is different from genetic modification and that gene-edited foods could have occurred naturally or been created through so-called “traditional breeding”.

At the core of this scientifically contested narrative is the lie that gene editing does not involve the insertion of foreign genetic material. This lie has been repeated without critique or question in the media and has served to silence criticism of the technology and obscure the real breadth of the government’s plans.

Under the proposed new legislation, while exempted PBOs can be created using newer style gene editing techniques, they can also be created using older style GMO techniques, including the insertion of foreign genetic material (transgenes). Indeed, right now all three of the crops being trialled in England under new liberalised field trial regulations, were created using transgenes.

This abandonment is also rooted in the lie that gene-edited products cannot be detected because the changes to a plant’s genome look no different to those that could have been created in nature or via traditional plant breeding. This ignores the fact that, in order to test gene-edited organisms, developers must have a way of detecting and tracking them, and that the protection of valuable GMO patents depends on a reliable detection method.

Even if this were not the case, existing audit trails provide robust provenance guarantees for a range of products in the food sector, including geographical origin, free-range and barn-reared poultry products. They could easily provide information on genetically engineered crops as well.

Worryingly, these lies have been circulated throughout Parliament in Defra briefing materials sent to MPs and peers. Many of our busy parliamentarians rely on official briefing documents and summaries of media reports rather than a careful reading of proposed legislation to inform them. This means that those who are debating and voting on this bill are misinformed – and some would argue are being deliberately misled.

As the Genetic Technology Bill continues its progress through Parliament, here are just a few reasons why labelling, transparency and traceability are vitally important.

It’s what the public wants

For many consumers, labelling is a clear red line. Last year the government asked the public if it supported the planned changes in regulation of genetic technologies. The overwhelming majority said no; 85% expressed the view that the genetic technologies used in farming should continue to be regulated, and therefore labelled, in the same way as other GMOs.

This result was not unexpected. Public polls by the Economic and Social Research Council and UK Research and Innovation, the Lloyd’s Register, the National Centre for Social Research, Food Standards Scotland and the Pew Research Center have all shown little public appetite for genetically engineered crops and foods.

A recent survey by the Food Standards Agency found that “consumers wanted thorough regulation and transparent labelling if GE foods reach the UK market”.

The Nuffield Council on Bioethics' public dialogue on genome-edited animals found, amongst other things, that participants had a strong interest and desire to influence the way in which the food they consume is grown and reared. Participants expressed significant concerns over commercial drivers of genome editing in farmed animals, as well as the ability of governance and regulatory systems to control the technology in a way that meets public aspirations for the UK’s future food system.

Citizens are major stakeholders in food and farming and their right to choose is also a right to refuse. This can only be exercised fully if products made from genetic engineering technologies or containing genetically engineered plants, animals and microbes are clearly labelled at all stages along the supply chain.

It provides information

Labels are the primary source of information about food for most people and as such they are vital to informed choice. During the oral evidence given at the Public Bill Committee hearings for the bill, Helen Ferrier, Chief Science and Regulatory Affairs Adviser at the National Farmers Union and Robin May, Chief Scientific Advisor of the Food Standards Agency, spoke out against labelling.

Professor May went so far as to suggest that we don’t need labels because most of us spend “less than six seconds considering each food item we purchase in the supermarket, which is not enough time to consider the label.”

That was a very selective (and unreferenced) figure which was used to suggest that people don’t apply critical faculties when they shop and don’t care about what they eat.

Instead of Prof May’s unreferenced study, consider this one, published in 2010 in the Journal of Public Health, which studied 6 European countries including, at the time, the UK. It found that on average shoppers spend 35 seconds looking at labels and that this time goes up or down according to the food they are considering. We spend less time on fresh produce but more on processed and highly processed foods. Highly processed foods remain the most common destination for GMOs of all kinds.

It’s worth noting also that the CLEAR campaign (of which we are members) is currently calling for mandatory method of production labelling. We see the genome editing issue as a bellwether here. If the government truly decides that how a genetically engineered plant or animal is produced is irrelevant and does not need to be included on the label, this takes away the mandate for any other kind of method of production labelling.

It promotes trust

Labelling and traceability are integral to transparency. Transparency, in turn, builds trust and fosters a stronger relationship between producer and consumer. Public trust in the food system to deliver safe, nutritious food in a way that does not inflict irrevocable damage on our ecosystems is declining. A recent survey by EIT Food suggested that shoppers trust smaller shops over large retailers because they are likely to be better informed about the origins of the products they sell.

Removing labelling from any type of genetically engineered food can only serve to damage trust further.

Currently, in the name of “building trust” amongst consumers, there is a concerted effort to “reassure” consumers about the safety and benefits of gene editing.

The long version of the narrative goes something like this: This is a complex issue that only scientists can understand. Citizens don’t trust this technology because they don’t understand it. It is, therefore, up to scientists to explain it in a way that educates and reassures citizens of its safety and plays up its potential benefits.

The short version of the narrative is: people are too stupid to understand this issue, so we can say anything we want without fear of being challenged.

You can’t build trust on a mixture of half-truths and lies, and this view does our citizens a gross injustice.

In all our encounters with the public over the years, we have come to understand that most people have a desire to understand and a more nuanced view of food and the food system than they are given credit for. What is more, for all the talk about trust from government and food agencies, we see very little evidence that government and food agencies have any trust in the public.

It’s not just about safety

Citizen concerns are not simply focused on safety and risk but encompass a whole range of issues informed by individual values. Within the food system, these values are addressed by other kinds of labelling: free range, fair trade, organic, cruelty free, no artificial ingredients, vegetarian and that much maligned concept, natural.

Labelling, in general, allows consumers to have knowledge and to choose a product they feel resonates with their lifestyle and values.

As we said in our own evidence to the Public Bill Committee, most citizens do care about what they eat. However, most of the food system is hidden from citizen view. Where it is visible people make positive choices. Citizens care about what they eat, and they care about how it was produced which is why people look for organic milk, free range eggs, pasture fed meat or fair trade coffee or chocolate.

It provides important feedback for retailers

Lack of provision for labelling only serves the biotech industry and allows it to dictate what people buy and eat. Biotech developers believe this creates a ‘level playing field’. In reality, the withholding of information skews buying habits and the real picture of consumer preferences.

Retailers use information on buying preferences (expressed through decisions to purchase or not) to inform what products they stock and what ingredients they use in their own brand food products. This information can also feedback through the production system. Without labelling this system of feedback is lost.

It is necessary for trade

One of the main reasons the UK wants to deregulate the products of gene editing is so that it can import goods, including genetically engineered food, from other countries such as the USA, Canada, Australia and Japan.

However, the global regulatory landscape is currently a jigsaw of many different approaches and requirements. What does not require labelling in one country may well require labelling in another country. Without traceability and labelling, imported products containing GMOs not exempted in one country, could enter the food systems of other countries untraceable and unlabelled.

In post-Brexit UK this is a particularly acute issue. By rebranding what constitutes a GMO, GM products produced here cannot legally be sold unlabelled in places like Northern Ireland. In addition, Scotland and Wales have made it clear, they have no wish to allow such products in their own food systems.

It is essential when things go wrong

Without labels it will be impossible to trace and monitor GMOs in the environment. Should something go wrong we will not be able to identify the cause. Traceability of these lab-created organisms is essential to allow recall if novel allergens, toxins or other human health or environmental safety issues emerge post-release.

Transparency – the bigger picture

It’s important also to understand that labelling is only one aspect of the broader issue of transparency. The others are traceability and coexistence.

Traceability means the ability to trace products through the production and distribution chains. It is necessary to facilitate control and verification of labelling claims; for targeted monitoring of potential effects on health and the environment, where appropriate; and for the withdrawal of products that contain or consist of GMOs should an unforeseen risk to human health or the environment arise.

Coexistence – the right to choose how to farm and the right to choose to buy products from different farming systems – is fundamental in the UK and no one system should be allowed to impinge on another. Equitable coexistence requires appropriate guidelines and measures to prevent field, farm and wider environment impacts (such as contamination) and to ensure consistency and enable post-release monitoring where needed.

As with labelling, provisions for traceability and coexistence in the Genetic Technology Bill are sketchy at best. Future regulation may – or may not – be brought in and it may – or may not – include provision for labelling.

A public register on the government or FSA website may – or may not – be implemented. While a register is better than nothing, how it will serve citizens wishing to make food shopping decisions remains to be seen.

How, for instance, will a busy mother wandering around a supermarket, with two children in tow, negotiate the murky waters of the government website to find the public register and then try to discern whether the food she wishes to purchase contains gene-edited ingredients? Only clear labelling will provide the information that consumers want at a glance.

Defra has indicated that voluntary guidelines or third party certifiers could take up the responsibility of labelling. But this option adds an unnecessary layer of complexity and cost for consumers and businesses. Statutory regulation, written into the laws of this land, is the clearest and most honest option.

But as things stand, too much is being left to half baked ideas and vague promises in some distant future. Defra’s stated position and the FSA’s apparent stance suggest that such promises are misleading, flaky and likely insincere.

If you want to see all GMOs labelled, please sign this petition run jointly by GM Freeze and Beyond GM.

Write to your MP and let them know that all genetically engineered foods, regardless of how they are produced, should be labelled in order to ensure we all have a choice of what we buy and eat.

This article first appeared on the Beyond GM website and is available here. It is reproduced on GMWatch with permission.