The forces that shaped Paterson’s rise to prominence are as active and influential as ever, writes Jonathan Matthews

Who funded disgraced MP Owen Paterson’s pro-GM lobbying still remains a mystery, thanks to the ruse he used to keep his funding secret, but we do know that from the start the GM industry played a key role in setting the agenda he so vigorously promoted after he became UK Environment Secretary in 2012. The campaign group GeneWatch UK did a lot to uncover this through a series of Freedom of Information requests that Paterson tried to obstruct.

Also playing an important part in shaping Paterson’s stances and PR messaging was someone closer to home.

A marriage of minds

In 1980, Paterson married Rose Ridley. In 2020, on Owen Paterson’s birthday, she took her own life. In the absence of a suicide note, there has been much speculation about her motives, with Paterson claiming the investigation into his lobbying activities was a major element.

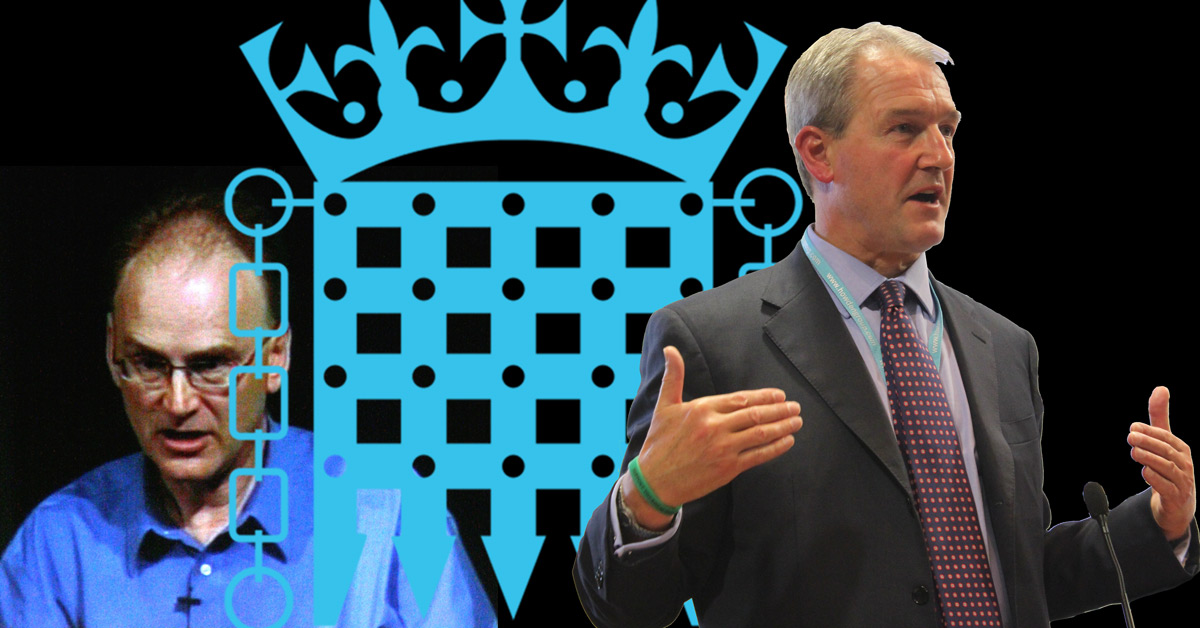

The Patersons’ marriage also helped bring about another partnership – one that still endures. Rose’s brother Matt (now Viscount Matt Ridley) has been described as “in many ways Paterson’s personal think tank” and as someone whose views helped Paterson, when a minister, “to overcome the flawed analyses sometimes presented to him by civil servants”. After Paterson left government, Matt Ridley was the sole policy advisor to Paterson’s UK 2020 think tank.

Who wrote Paterson’s script?

An indication of the key role Ridley has played in Paterson’s output is provided by the headline-grabbing speech Paterson gave soon after losing his ministerial post. In this, he made light of the threat of climate change and said Britain should focus not on developing renewables but shale gas and nuclear reactors. When his speech was emailed to the media, the document’s properties showed its author to be not Owen Paterson but Matt Ridley.

Ridley subsequently confirmed that he had assisted in the speech’s preparation while doing his best to downplay the extent of his authorship. But even a cursory glance at Ridley‘s public statements on environmental issues leaves no doubt as to how closely they match with those put forward by his brother-in-law.

According to Ridley, rural Britain would be better off with more badger culls; GM crops like golden rice will save the lives of hundreds of thousands of children; climate change is doing more good than harm; fracking has not produced a single environmental problem; disinvesting in fossil fuels merely plays into the hands of the Chinese; wind power is a total fraud; organic food isn’t better for us or the environment; elephants should be hunted for their ivory; planning laws should be scrapped; recycling should be stopped; and banning neonicotinoids is bad for bees.

With policy advice like that, little wonder Owen Paterson has been described as “the worst environment secretary the UK has had for decades” (Friends of the Earth) and “the worst environment secretary Britain has ever suffered” (George Monbiot), or that the conservation campaigner Miles King asked, “Is it a coincidence that Paterson’s partner in crime, Matt Ridley, is the nephew of the late Nick Ridley, the last most damaging environment secretary?”

Can’t keep a bad man down

But, you may be thinking, given that it’s now 7 years since Owen Paterson was last a minister, more than a year since the think tank he set up became defunct, and he has just quit parliament as an MP, can’t we just confine him to the history books and forget all about him? Possibly not. This kind of disgrace isn’t always as catastrophic as one might imagine, as Paterson’s brother-in-law’s career shows all too clearly.

According to parliament’s Treasury select committee, Matt Ridley was responsible for a “high-risk, reckless business strategy” at the UK bank Northern Rock, where he was chairman from 2004 to 2007, that led to its near collapse after it experienced Britain’s first run on a bank in 140 years. Ridley resigned, and the UK Government eventually had to bail out the bank to the tune of £37 billion.

Even Ridley says he is filled with remorse for what happened and that his leadership of the failed bank is a “catastrophic black mark” on his CV. It’s far from the only one.

The extreme climate scepticism which marks so many of his contributions to public life has frequently not been accompanied by a declaration of the substantial open-cast mines he has had on his massive estate in Northumberland or the fact his family’s wealth is built on coal. This led the renowned climate scientist Michael Mann to comment, “Matt Ridley is a coal baron who profits directly from the sale of fossil fuel reserves while the rest of us suffer the consequences. You couldn’t invent a better climate-change-denier villain.”

But thanks to Ridley’s excellent connections within the Conservative Party and the right-wing media, and the popularity there of his free-market fundamentalism and anti-green views, he has suffered few if any consequences from being a disgraced banker and a “climate-change-denier villain”. He has continued to be a highly paid newspaper columnist, first for the Times and more recently for the Daily Mail. And only a year after succeeding his father to the viscountcy in 2012, he was elected to the House of Lords by fellow Conservative hereditary peers, beating even a former cabinet minister in the poll.

Similarly, Ridley has served for years on the House of Lords’ Science and Technology Select Committee, despite being known for climate denial and “epic blunder-fests of disinformation” in his science writing.

Ridley is also one of only five members of the government-appointed Regulatory Horizons Council, which is supposed to provide the government with “impartial, expert advice on the regulatory reform required to support (the) rapid and safe introduction” of innovative technologies. Ridley and the RHC, needless to say, have been pushing for GM deregulation.

Friends in high places

Paterson too has friends in high places. In fact, the reason that the lobbying scandal has developed to the extent it has is due not only to how “egregious” Paterson’s breaches of the rules on lobbying were, but the extraordinary lengths the government went to on his behalf, after it was proposed he be suspended from parliament.

According to Chris Bryant, chair of the Commons’ Committee on Standards, the government’s campaign was marked by “bullying and determination” to “give Paterson a “get out of jail free” card. For months, they lobbied anyone they could find. They spread noxious rumours about members of the (standards) committee. They tried to get the speaker to block the publication of our report. They endlessly misrepresented the process…”

Even after Paterson quit the Commons amidst the exploding scandal, No. 10 refused to rule out putting Paterson into the Lords by giving him a peerage.

“The bitch that bore him”*

Whatever happens to Paterson, the forces that shaped the agenda he promoted are as active and influential as ever. In fact, the deregulatory agenda set by the GM industry just a couple of months before Paterson took office is now being pursued more relentlessly than ever by the current government, which has more ability to manoeuvre post-Brexit.

Particularly important in maintaining the trajectory for the return of GM crops to Britain has been a group of parliamentarians – Owen Paterson and Matt Ridley among them – that continues to operate like the parliamentary arm of the GM industry, which directly funds their operations.

The Owen Paterson scandal has helped shine a light on concerns about how such parliamentary groups are being used to lobby on behalf of business interests, including the Westminster lobby group that has been busy paving the way for the dismantling of GM safeguards.

* “Do not rejoice in his defeat, you men. For though the world has stood up and stopped the bastard, the bitch that bore him is in heat again.” – Bertolt Brecht

Image of Matt Ridley by Tara Hunt, Montreal, via Wiki Commons. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) licence. Image of Owen Paterson by Policy Exchange via Flickr and Wiki Commons. Reproduced und the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) licence. Image of portcullis by Charles Barry via Wiki Commons. In the public domain.