Lack of critical assessment can delay innovation, jeopardise public trust, and waste resources, especially in the Global South, say scientists. Report: Claire Robinson

Two GMO crop researchers have published an incisive commentary denouncing pro-GMO hype, especially from the point of view of the harm it can do in the Global South.

Devang Mehta of the University of Alberta in Canada and Hervé Vanderschuren of the research university KU Leuven in Belgium published their commentary in Nature Reviews in Molecular Cell Biology.

The summary of their article reads: "Lack of critical assessment and responsible reporting of proof-of-concept agricultural biotechnologies such as CRISPR–Cas can delay innovation, jeopardise public trust and waste resources, especially in the Global South. In this commentary, we propose solutions to facilitate a more responsible innovation pipeline and to realize the potential of biotechnology in agriculture."

The article can be read for free here. Mehta also provides a handy summary on Twitter. The gist of the article is as follows.

Destructive "hype cycle"

Over the years the authors have seen instances where new plant biotechnologies and new applications of technologies are announced with great fanfare in well-regarded journals – for example, a new application of CRISPR, tested in the commonly used experimental model plant Arabidopsis or tobacco.

These lab-based discoveries are seen by researchers around the world, including in the Global South, who then start working on taking that initial proof-of-concept finding and applying it to a crop, say, cassava, hypothetically.

But back in the world of basic science (usually in rich countries), people start to realise the limitations of the new technology. These get much less attention. The scientists working on cassava (in our example) continue to test the new technology, spending precious funds, only to see it fail.

The incentives are stacked against sharing negative results, so they either never see the light of day, or are delayed. Over time science self-corrects, and this is seen as a natural "hype cycle". But scientists in the Global South have now wasted money for no benefit.

It is they who are disproportionately impacted by what the rest of the world considers the normal, self-correcting process of scientific innovation.

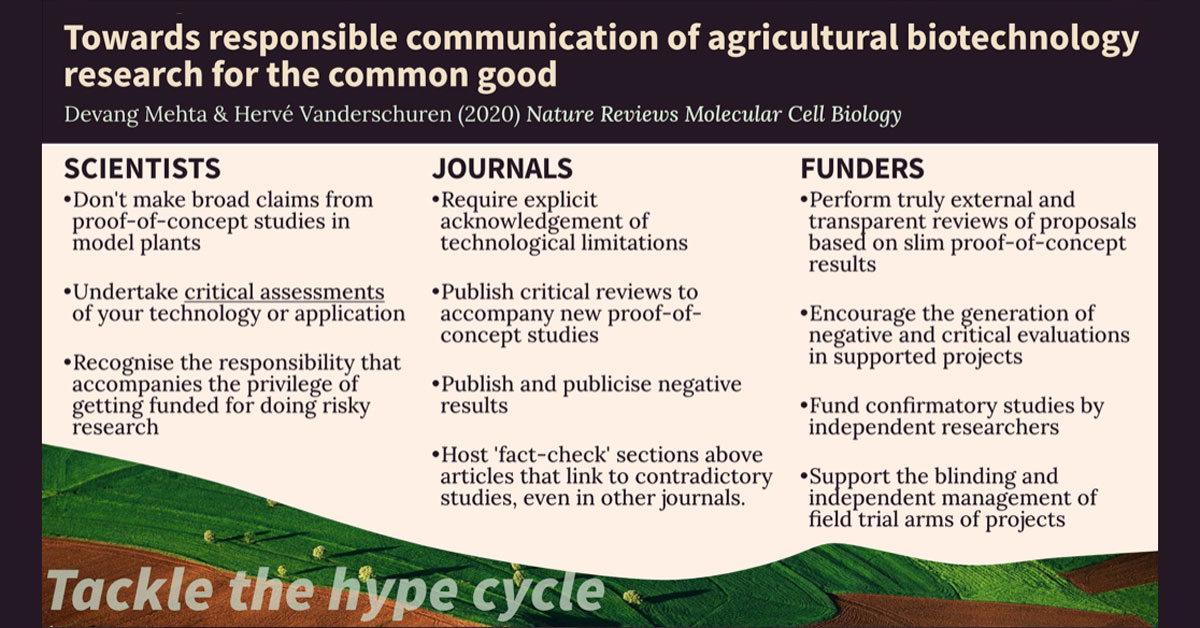

The authors of the new paper recommend that fixing the problem requires reforms among three sectors of the scientific establishment – scientists, journals, and funders.

Scientists should:

* Not make broad claims from proof-of-concept studies in model plants

* Undertake critical assessments of their technology or application

* Recognise the responsibility that accompanies the privilege of getting funded for doing risky research.

Journals should:

* Require explicit acknowledgement of technological limitations

* Publish critical reviews to accompany new proof-of-concept studies

* Publish and publicise negative results

* Host "fact-check" sections above articles that link to contradictory studies, even in other journals.

Funders should:

* Perform external and transparent reviews of proposals based on slim proof-of-concept results

* Encourage the generation of negative and critical evaluations in supported projects

* Fund confirmatory studies by independent researchers

* Support the blinding and independent management of field trial arms of projects.

Mehta and Vanderschuren conclude their paper, "The effects of uncritical promotion of proof-of-concept research are multifarious. They include the loss of public trust in biotechnology due to the failure to follow up on bold promises, waste of time and resources in countries that can least afford it, and a delay in real innovation as a result."

We could not have put it better ourselves. Who knew that GMO crop researchers would one day publish a peer-reviewed article that said pretty much the same things that GMWatch and other GMO critics have been saying for decades? It's all the more surprising that the article appears in a Nature journal, as these journals are so often uncritically pro-GMO.

GMO cassava failure

This is not the first time that Mehta has been openly critical of GMO hype.

In 2017 he called out GMO and pesticide promoter Kevin Folta on Twitter after Folta falsely claimed success for a GMO CRISPR gene-edited virus-resistant cassava project in Uganda. The lab that Mehta worked in for his former position at ETH Zurich was involved in this project, which was called the Global Cassava Partnership for the 21st Century (GCP21).

Folta had tweeted, “Ugandan biotech cassava field trials show another success in virus resistance, protecting a crop that feeds >800 M" (over 800 million people).

But Mehta quickly advised Folta against claiming this, because the genetic modification of the cassava had broken cassava’s existing natural resistance to a different, more widespread virus.

In addition, the engineered CRISPR virus resistance led to the emergence of a novel mutant virus. If it had escaped, it might have put at risk the entire cassava crop.

Mehta and his colleagues described the project's demise in papers on the bioRxiv pre-print site and subsequently in the peer-reviewed journal Genome Biology.

Following this failure, Mehta wrote an article announcing that he was leaving GMO research. In the article, he did not admit to the inherent problems of the technology, choosing instead to blame public “backlash and criticism” of GM.

"Private philanthropy" is part of the problem

The dangerous debacle with the CRISPR-edited cassava was just the latest in a years-long string of failed attempts to genetically engineer virus resistance into cassava. Non-GM approaches, on the other hand, have enjoyed consistent success but struggle to find funding to roll out more widely. According to Dr Angelika Hilbeck, a researcher with long experience of cassava breeding programs in Africa, the Gates Foundation and USAID "generously" fund the GM programs while giving "little" to the non-GM programs.

Perhaps this is why Mehta and Vanderschuren take a potshot in their commentary at "private philanthropy and international aid agencies, who may lack specialized in-house scientific knowledge". Thus, the authors say, these entities are guilty of carrying out uncritical and premature assessments of early proof-of-concept studies, which "may lead to the funding of projects with a high risk of failure".

The authors do not explicitly identify the Gates Foundation as an example of problematic "private philanthropy" organisations. But there is no doubt that the Foundation and its pet project, the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), fits the description. AGRA has wasted enormous amounts of money and resources on chemical-intensive agriculture projects in the Global South and is committed to disseminating GM technologies. According to Timothy Wise of Tufts University Global Development and Environment Institute, these initiatives embody a "failing model" with "failing results".

The GCP21 cassava project

The Gates Foundation and the international aid agency USAID, along with Monsanto, are known to have poured funds into cassava research and development, though the funders of GCP21 remain undisclosed. We do know that the Gates Foundation and USAID were among the sponsors of the GCP21’s second scientific conference, held in Uganda in 2012, as were the Danforth Center and the GMO firms Monsanto, Syngenta, and Cibus. We also know that the European Union (under its FP7 "research and innovation" programme) and ETH Zurich funded Mehta and Vanderschuren's work on cassava under GCP21.

The GCP21 has claimed that it consists of 45 member institutions working on the research and development of cassava, but the part of its website that is meant to name its partners contains no information. However, GCP21 is chaired by Dr Claude Fauquet, former director of the International Laboratory for Tropical Agricultural Biotechnology at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center. The Danforth Center itself was launched with a $50 million gift from Monsanto.

It was Fauquet and the Danforth Center that led the numerous failed attempts to develop GM virus-resistant cassava, dating back to the 1990s.

Distractions

Mehta and Vanderschuren are to be congratulated on their refreshing honesty, although they don't seem to have given up hope that one day GM will succeed where thus far it has repeatedly failed. They conclude their commentary with the claim, "CRISPR–Cas and other new biotechnologies hold great potential to address food insecurity and raise farmer incomes in the Global South", though they wisely caution that "responsible communication and critical assessment" will be needed before that potential can be realised.

We, on the other hand, do not believe that GM technologies are relevant to solving the challenges of food and farmer income security in the Global South. On the contrary, we think they are an expensive distraction from proven effective agroecological and traditional breeding successes.

What's more, it is likely that if the recommendations of critical assessment, transparency, and independence put forward by Mehta and Vanderschuren had been followed from the start of the agbiotech venture, it would never have got off the ground.

Image is from Devang Mehta's Twitter feed (@drdevangm)

https://twitter.com/drdevangm/status/1357878126819246081/photo/1