“Grassroots” defenders of pesticides and GMOs keep on faking it! Report by Jonathan Matthews

Five thousand tractors caused severe disruption in Berlin last week as farmers protested against the German government’s environmental protection policies. These include plans to limit the use of fertiliser in order to tackle nitrate pollution in groundwater, and to phase out glyphosate by 2023 to protect biodiversity.

Meet fake Farmer Willi

One of the German government’s most outspoken critics is Dr Wilhelm Kremer-Schillings, or “Farmer Willi”, as he styles himself. Through his blogging and campaigning against pesticide restrictions, in favour of GMOs, and in defence of companies like Bayer/Monsanto, he has become one of Germany’s best known farmers.

And Farmer Willi is a man of action, not just words. Prior to the Berlin protest, he led farmers across Germany in pounding large green crosses into their fields in a highly visible protest against the environmental policies he says will be a deathblow for Germany’s agricultural sector.

But according to an article in the German newspaper Taz, a more accurate nickname for Kremer-Schillings might be “Chemical Willi”. That’s because, despite promoting himself as a small farmer working a “traditional farm” in the Lower Rhine, his career turns out to have involved very little active farming and a great deal of working with agrichemical interests.

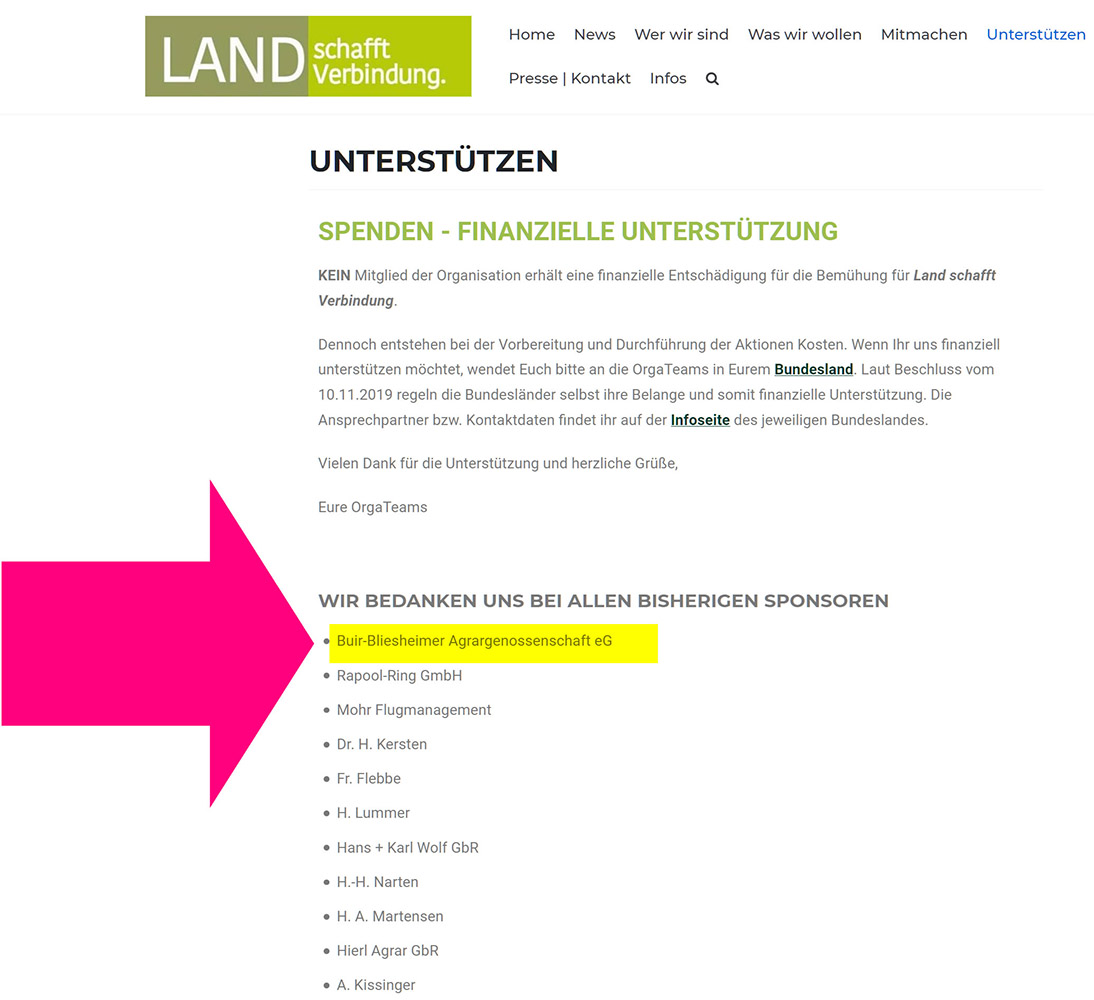

Taz says this included a stint in the chemicals division of the Schering Group, later taken over by Bayer, as a project manager for Betanal – a weedkiller suspected of causing cancer. Kremer-Schillings also advised farmers on pesticides for the sugar producer Pfeifer & Langen. And he has served first as Chairman and now Vice Chairman of Buir-Bliesheimer Agrargenossenschaft eG, a sizeable farm cooperative (annual turnover: 120 million euros) that trades heavily in fertiliser and pesticides, like glyphosate.

The green cross and Berlin protests aimed to challenge the government’s plans to impose restrictions on these farm chemicals. And interestingly, Willi’s company tops the list of sponsors that the Berlin protest organisers thanked for their support.

But when he launched his Farmer Willi website and his book, none of Willi Kremer-Schillings’ many agribusiness connections got a mention.

Faking it in France

Farmer Willi is far from alone among “grassroots farmers” opposing farm chemical restrictions, and/or promoting GMOs, in having a PR platform that airbrushes out his corporate connections.

A French equivalent is Vincent Guyot, who was prominently portrayed in the French media as the man giving voice to the despair of France’s many small farmers at the prospect of a glyphosate ban. An article in the newspaper L’Express, for instance, emphasised that Guyot was just an ordinary peasant farmer, who was not even a member of a farmers’ union, let alone “a lobbyist for Monsanto” or some other agrichemical giant.

Guyot shot to fame in 2017 after the financial daily Les Echos published his very personal appeal against a glyphosate ban under the headline Me, Vincent, farmer and user of glyphosate. In this open letter, published just days before the European Union was to decide whether to re-approve glyphosate, Guyot said he wanted “to seize this opportunity, to shout one last time before my voice and those of my [farmer] colleagues are silenced”.

And this grassroots farmer’s “cry of despair”, as he called it, had such an impact that when, contrary to all Guyot’s fears, glyphosate was not banned in the EU, Les Echos proudly re-published his impassioned defence of the chemical.

But in May of this year the paper had to pull Me, Vincent, farmer and user of glyphosate from its website after the French TV documentary makers Envoyé Spécial disclosed that Guyot’s heartfelt plea was actually the work of a PR agency working for Monsanto, the maker of Roundup, the highly lucrative glyphosate-based weedkiller.

Astroturfing across Europe

Guyot turns out to be just one cog in a much bigger PR strategy – a supposedly grassroots-led campaign by farmers in defence of glyphosate, active under different names across eight European countries (France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Spain, and the UK) in the run up to glyphosate’s renewal.

Investigations by Greenpeace, The Independent and Le Parisien, among others, exposed how the pro-glyphosate campaign had been conceived and realised by the Monsanto PR and lobbying firm Red Flag Consulting, in coordination with FleishmanHillard and Lincoln Strategy Group, which took stands at farm shows and used hostesses to entice farmers to sign up for its astroturf campaign.

After it emerged that groups like Agriculture et Liberté in France were actually led by PR people working for Monsanto, their websites and Twitter accounts got pulled – just like Vincent Guyot’s ghostwritten cri de coeur.

“Grassroots” rebellion in India

Sometimes it’s not necessary to invent grassroots movements, in the way Monsanto’s PR people did in Europe, because existing groups can be drafted in to play the part instead.

In June 2019, the pro-GMO campaigner Mark Lynas began talking up what he claimed was to be “the world's first pro-GMO protest”.

Lynas said it would involve Indian farmers planting banned GMO seeds in what he called “Gandhi-style civil disobedience”. This attention-grabbing campaign was being led by a farmers’ group, Shetkari Sanghatana, that Lynas described as “very grass roots”.

But only a few months earlier Lynas had been taken to task for making bogus claims about farmers in Tanzania, so the spectacle he conjured up is worth a little scrutiny.

It turns out that the protest organisers, Shetkari Sanghatana, are no mass movement of grassroots farmers but an allegedly well-funded fringe group created by the late Sharad Joshi, a rightwing economist and Member of the Advisory Board of the Monsanto-backed World Agricultural Forum, an organisation whose founder and first Chairman was for many years Monsanto’s director of public policy.

Joshi was also Chairman of Shivar Agroproducts Ltd. But he is best remembered for his ultra-libertarian ideology, and the farmers’ groups and the political party (Swatantra Bharat Paksh) that he founded were all vehicles for promoting his free market fundamentalism.

Lynas was not the first to present Shetkari Sanghatana as representing ordinary Indian farmers. A full two decades earlier, the European biotech industry and their PR firm Burson-Marsteller brought some of Shetkari Sanghatana’s leading lights to Europe to try and counter the view that Indian farmers opposed GMO crops. To that end, they were toured around five different countries by the industry’s lobby group, EuropaBio, which in a press release presented this free market fringe group, which is largely confined to the state of Maharashtra, as “the mainstream farmers’ movement in India”.

Faking it in Africa

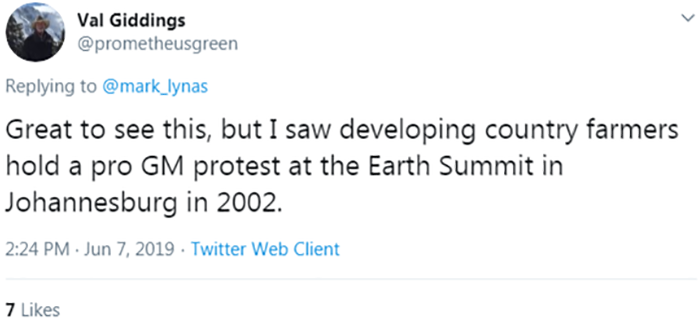

That this kind of fakery has deep roots was confirmed when Mark Lynas announced “the world's first pro-GMO protest” on Twitter, and former Biotechnology Industry Organization Vice President, Val Giddings, responded, “Great to see this, but I saw developing country farmers hold a pro GM protest at the Earth Summit in Johannesburg in 2002.”

The protest Giddings is referring to was well-publicised at the time, with articles on it popping up all around the world. Giddings himself even claimed that it marked “something new, something very big” that would make us “look back on Johannesburg as something of a watershed event – a turning point”. What made the march so pivotal, Giddings said, was that for the first time, “real, live, developing-world farmers” were “speaking for themselves”.

But were they?

James MacKinnon, who reported on the summit for Adbusters and who witnessed the march first hand, tells of seeing mostly impoverished street traders, who seemed aggrieved not about GMOs but about the South African authorities banning them from using their usual trading places in the streets around the summit. These traders had been recruited for a march that was said to be about “freedom to trade”, and the flier for the march made no mention of GMOs.

There were some real farmers at the march though. Mackinnon says he spotted a small group with T-shirts and placards with anti-environmentalist slogans like “Stop Global Whining”, “Save the Planet from Sustainable Development”, “Say No To Eco-Imperialism” and “Biotechnology for Africa”. But he discovered these props had all been made available to the marchers by the protest’s free market organizers. And when Mackinnon tried to converse with some of the farmers wearing the T-shirts, “They smiled shyly; none of them could speak or read English.”

Faked in the USA

Fake pro-GMO protests were born in the USA. In the same year that Burson-Marsteller was helping Shetkari Sanghatana lobby for GMOs across Europe, the firm was also performing its PR magic in Washington DC. There, a street protest against genetic engineering outside an FDA public hearing was disrupted by a group of African-Americans carrying placards such as “Biotech saves children’s lives” and “Biotech equals jobs”. Burson-Marsteller, the New York Times discovered, had paid a Baptist Church from a poor neighbourhood to bus in these “demonstrators” as part of a wider campaign “to get groups of church members, union workers and the elderly to speak in favor of genetically engineered foods”.

Over the years, fake protesters have been joined by fake citizens, fake journalists and journalism, fake independent scientists by the bucketload, fake regulation, a fake national science academies’ report, and even a fake agricultural research centre.

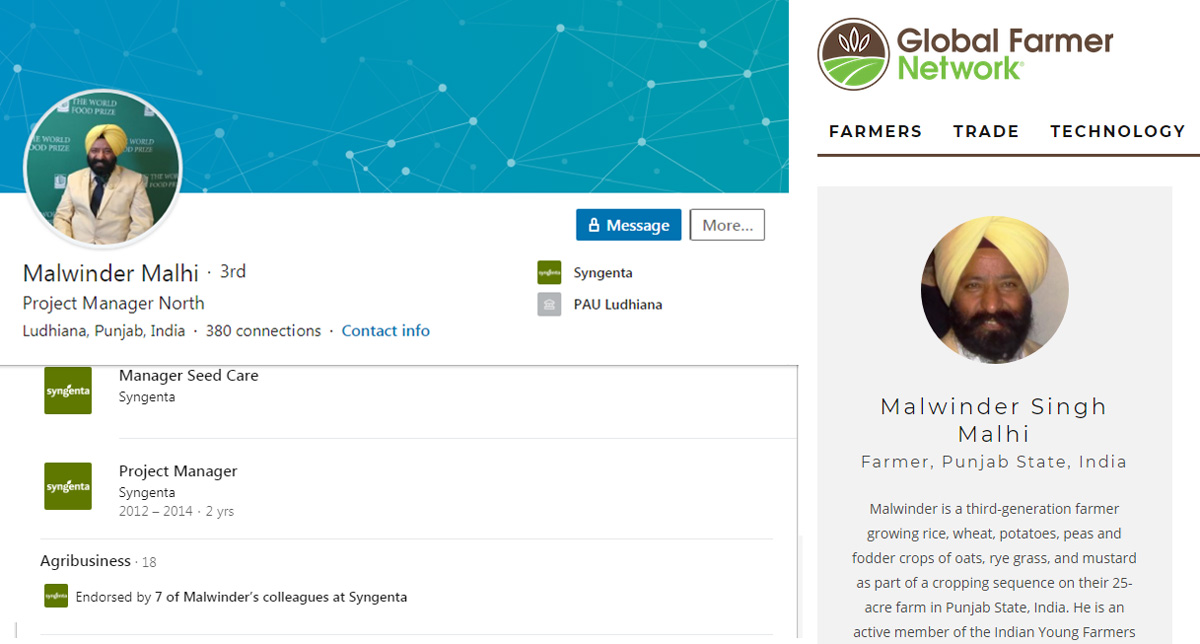

The US has served as the biotech industry’s chief propaganda hub for promoting such fakery to the world, as can be seen with the illegal GMO seed planting in India. Among the notable cheerleaders promoting the protesters’ cause were the Gates-backed GMO propaganda outfit The Alliance for Science, which pays Mark Lynas to lobby for GMOs; CS Prakash of AgBioWorld, who has long served as a conduit for Monsanto disinformation; Bayer-consultant and Monsanto collaborator Kevin Folta, who made a podcast on the protests with CS Prakash; and Malwinder Singh Malhi, who in an opinion piece for the Global Farmer Network explained why he thought the only possible response to the illegal GMO planting was: “Make it legal”.

The Global Farmer Network, despite its name, is a US-based pressure group formerly known as Truth about Trade and Technology, which lobbies for GMOs and for open markets for US agribusiness, but uses farmers from around the world to help promote its agenda. According to its former chairman, Bill Horan, “People trust the voices of farmers”, and the Global Farmer Network is in the business of “spotting and nurturing” such voices and then placing their “commentaries in publications ranging from the Wall Street Journal to the Daily Nation, the leading newspaper of Kenya”.

The Global Farmer Network’s profile for Malwinder Singh Malhi states that he is “a third-generation farmer growing rice, wheat, potatoes, peas and fodder crops of oats, rye grass, and mustard” on his 25-acre farm in Punjab, India. But strangely Singh Malhi’s Facebook profile makes no mention of his being a farmer, identifying him instead as a project manager for the agrichemical giant Syngenta. His LinkedIn page also makes no mention of his farming, but does list the posts he’s filled at Syngenta over the years, while his agribusiness skills are endorsed by many of his Syngenta colleagues.

In his Network article, by contrast, there are several mentions of what he grows and doesn’t grow on his farm, but there is no mention of the fact that he works for a multinational company with major interests in the topic he is writing about – the acceptance of GMOs. As with “Farmer Willi”, his deep involvement with corporate interests has been airbrushed out of his farmer’s narrative. After all, people trust the voices of farmers – industry honchos, not so much.