Dissent crushed to protect New Brunswick’s glyphosate addiction

Wildlife biologist Rod Cumberland has been fired from the Maritime College of Forest Technology (MCFT) in New Brunswick, Canada.

A June 20 letter from the college lists several reasons for his dismissal. But the college’s former director, Gerald Redmond, says the real reason is Cumberland‘s critical stance towards the use of glyphosate in forestry. “There is no other explanation,” Redmond told the National Observer.

Glyphosate is killing New Brunswick’s deer

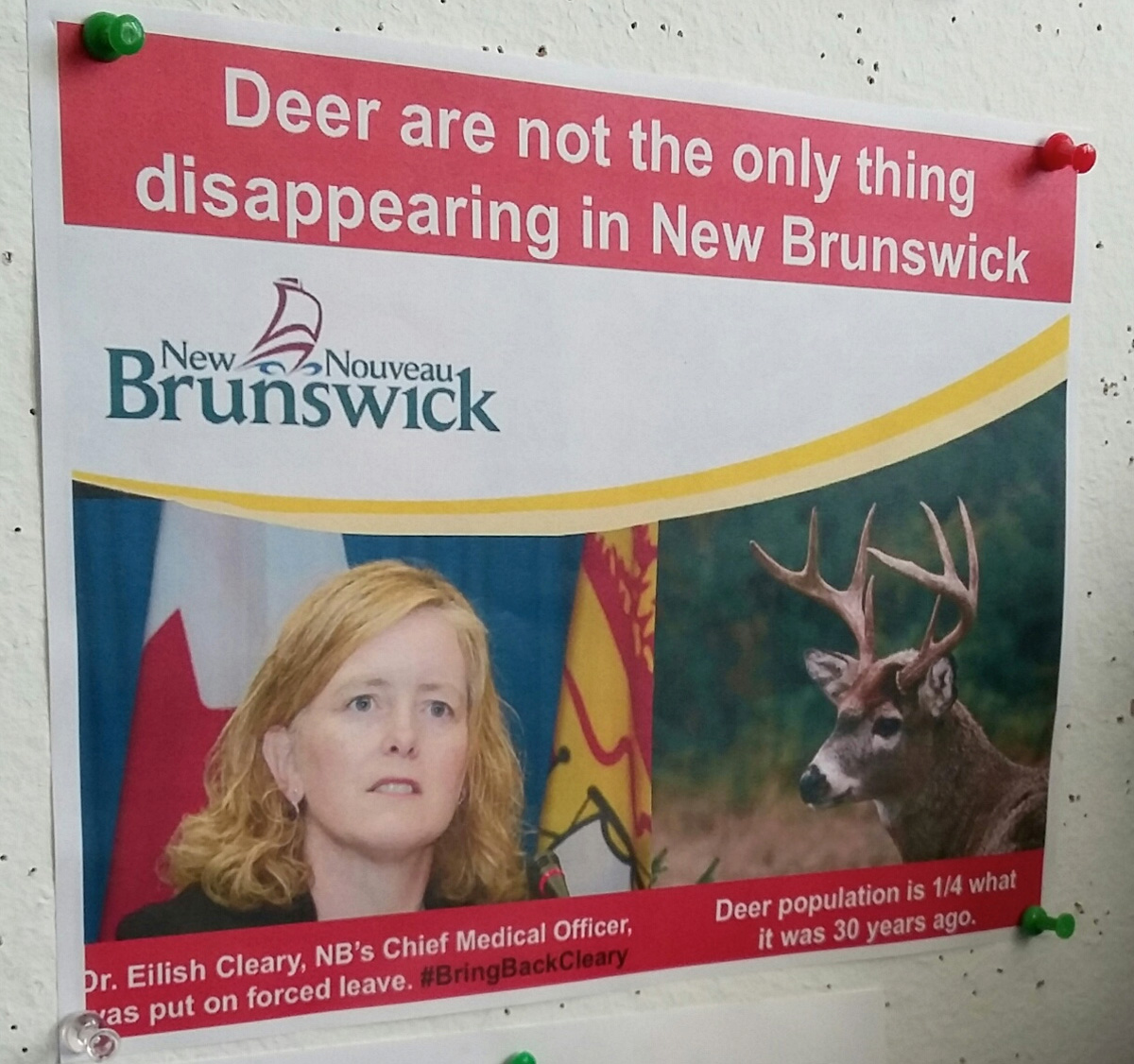

Cumberland, the former chief deer biologist for the province (pictured left in the image above), argues that the heavy use of glyphosate in forestry has had a devastating impact on New Brunswick’s white-tailed deer population, which plummeted by over 70% from 286,000 in the mid-1980s to just 70,000 by 2014.

Redmond, who is also a wildlife biologist, says that when he was the college’s director he experienced “attempts to sanction Rod for speaking up on this important wildlife issue”.

According to Redmond, “The other issues cited in [Cumberland’s] letter of termination that focus on his classroom management and teaching approaches are simply ‘window dressing’ to cover up the real reasons for his dismissal.”

Redmond says Cumberland should definitely be reinstated. “Rod Cumberland is one of the finest, most experienced and professional wildlife biologists that I have had the pleasure to know and work with. On top of that, he is an incredible educator and communicator.”

Second sacking

Within 24 hours of his publicly linking Cumberland’s dismissal to glyphosate, Redmond too was fired by the college he at one time directed and where he was still teaching.

The Canadian Association of University Teachers, which represents 77,000 academics across Canada, has condemned the dismissal of both teachers, saying it appeared to show the college had “violated their academic freedom and their basic right to due process”.

Chief medical officer sacked while investigating glyphosate

But Cumberland and Redmond are not the only experts in New Brunswick whose dismissals have been linked to concerns about glyphosate.

In 2015 New Brunswick’s chief medical officer, Dr Eilish Cleary (pictured right in the image above and in the poster below), was investigating the human health impacts of the herbicide when she was suddenly put on leave without being allowed to discuss the reasons. She told reporters, “I was surprised and upset when it happened. The whole situation has caused me significant stress and anxiety. And not being able to talk about it makes it worse.”

A month later Dr Cleary was fired, bringing an abrupt end to her role in the investigation.

It was subsequently reported that New Brunswick's Health Department had “concluded ‘a satisfactory agreement’ that was legally consistent with other instances of dismissal without cause”. But they refused to make Dr Cleary’s actual severance terms public. Eventually, after Radio-Canada took them to court, they were forced to disclose that they had paid her $720,000 (equivalent to over half a million US dollars).

Mario Levesque, a political science professor at Mount Allison University, said the size of the settlement could help explain why the government had tried to keep it secret. He told CBC News, “I think this is hush hush money.”

Silencing dissent in New Brunswick

Eilish Cleary’s willingness to speak out on controversial public health issues was well known. In 2012, she had produced a report that drew attention to the “social and community health risks” related to fracking. The provincial government considered keeping the report secret but eventually agreed to publish it.

Following that episode, Cleary said she had had to “re-affirm my right and my ability to speak”. But Mario Levesque says her sacking shows the government might have found another way to silence her.

Rod Cumberland is also known as someone not afraid to go public with his concerns. Redmond describes him as a person who “does his research and is never intimidated to speak out when something is amiss”.

And that kind of outspoken dissent is “rare” in New Brunswick, according to an article in Le Monde Diplomatique: “Teachers, civil servants and politicians fear reprisals; some have been intimidated.”

The article, published earlier this year, gives both Rod Cumberland and Tom Beckley, a professor of forestry at the University of New Brunswick, as examples of experts who have come “under pressure when analysing the impact of this weedkiller on local fauna and the lack of transparency in the provincial government’s management of forests”.

According to Gerald Redmond, “A lot of good people in government and elsewhere have been intimidated.” Cumberland, who used to work for the provincial government, is even reported as saying that “numerous other government officials who’ve opposed current forest practices have been removed from their posts”.

And when the chief medical officer was sacked, the leader of New Brunswick’s New Democratic Party pointed out that “silencing New Brunswick's most prominent government scientist” sent a clear signal: “We cannot expect civil servants to do their job when even prominent public officials like Dr Cleary are muzzled.”

Fixing the glyphosate report

Eilish Cleary had indicated even before she started her glyphosate study that she and her staff agreed with the World Health Organisation’s cancer agency IARC’s finding that glyphosate was a probable carcinogen. But the report that eventually emerged under her acting successor downplayed the significance of IARC’s finding and concluded that there were no significant reasons for concern about the use of glyphosate in New Brunswick, including in forestry.

Although there was an attempt to keep the report under wraps, when it was finally published, it contained no details as to who had been involved in its preparation. However, in the Monsanto Papers – the discovery documents released in the course of US federal and state litigation – is an email from Monsanto Canada which says that Len Ritter, a toxicologist from Canada’s University of Guelph, had confirmed to them that he had been “contracted by the province of New Brunswick… to assist with their review of the IARC findings on glyphosate”. Monsanto Canada’s Regulatory Affairs Lead continues, “While Len does not want to work with us directly, it sounds like he is delivering the interpretations and messages we would like to have put forward on this subject.”

When New Brunswick contracted Ritter to help with the report, they would have known exactly what they were getting. He is well known for downplaying the dangers of pesticides. Indeed, when he was working for the federal regulator Health Canada in the early 1980s, he even vouched for the safety of 2,4,5-T – the dioxin-laced component of Agent Orange. Thanks to the support of those like Ritter, 2,4,5-T was not banned at a federal level in Canada till after 1985, even though its US sales had been suspended completely by 1979.

And according to the investigative journalist Bruce Livesey, Ritter was also “one of three go-to scientists on a pro-glyphosate website sponsored by the New Brunswick government and forest companies”, which they set up to push back against Rod Cumberland’s findings on glyphosate. Later, Ritter was sent to cities and towns across New Brunswick to reassure local residents about glyphosate spraying.

So who’s protecting glyphosate?

About 85% of New Brunswick is forested and forestry is said to be “the economic backbone of the province”.

New Brunswick has permitted four forestry firms to lease out its immense tracts of public (Crown) forest, with J.D. Irving Ltd being the biggest licensee. The Irvings are one of Canada’s wealthiest families and have been called “Canada’s robber barons”. Their level of control in New Brunswick is such that Bruce Livesey calls it a “company province”.

The majority of the glyphosate sprayed in New Brunswick is used in forestry – almost half of it by J.D. Irving. That is because glyphosate is a key component of their business strategy. This involves clear-cutting forest and then, as the area starts to regenerate, aerially spraying glyphosate to kill off all the hardwood trees. This is supposed to enable the more rapid growth of profitable softwoods, which are destined for the province’s pulp and paper mills.

But Rod Cumberland points out that it is hardwood foliage that provides the main source of food for white-tailed deer. So 32,000 acres of forest being sprayed every year with glyphosate equals a massive reduction in deer food. He estimates that over the course of 20 years that level of spraying means removing more than half a billion tons of their food.

When Cumberland started going public with his findings, it helped galvanize opposition to glyphosate spraying in New Brunswick. As a result, says Livesey, Cumberland “became a primary target of the forest industry and its supporters. Since at least 2014, J.D. Irving and other forest companies, along with provincial and federal government officials, have tried to discredit Cumberland.”

Livesey quotes Lois Corbett of the Conservation Council as saying, “If your business is about making money out of pulp and paper products, and the widespread use of glyphosate, then Rod is a problem for you. If you’re a corporate guy, you would ask ‘Why don’t we just fire the guy?’”

Needless to say, the Maritime College of Forest Technology’s board is dominated by “corporate guys” from forest companies, including J.D. Irving.

Postscript: The wider problem of corporate capture

The corporate control in New Brunswick is so blatant that it has made headlines even outside of Canada. But the problem of corporate capture goes far wider than the issue of a “company province”.

According to the Monsanto Canada email released as part of the Monsanto Papers, the glyphosate-defending Len Ritter wasn’t only contracted by New Brunswick following IARC’s rating of glyphosate as a probable carcinogen. He was also contracted by “the Ontario Public Health Agency, among others” (emphasis added) to assist them with their responses.

Similarly, when in 2011 Ontario decided to investigate the health risks associated with the use of Agent Orange in Canada, it appointed Ritter to oversee the investigation. But as a leading member of Ontario’s Legislative assembly asked, how could those concerned about this issue “feel confident that there will be an independent review when we know that Len Ritter was the very guy who approved the use of Agent Orange when he was the head of that department [at Health Canada] back in the 1980s?”

In 1994, while still at Health Canada, Ritter took a leave of absence during which he testified for industry that Monsanto’s genetically engineered cattle drug rBGH was “clearly and emphatically” a “safe product”. He was accused by whistleblowers within Health Canada of pressuring them to approve rBGH despite their many misgivings.

Ritter’s industry-friendly approach reflects a far wider problem, according to one of those whistleblowers, the late Shiv Chopra. Chopra recounted in his autobiography how at an interview for a change of post at Health Canada, he was asked, “Suppose you are selected for this post, whom would you consider to be your client?” Chopra replied, “The public, of course.” The interviewer said, “No, it is the industry.”

Chopra titled his autobiography Corrupt to the Core, as that was his eventual judgement on the extent of Health Canada’s corporate capture.

Chopra‘s book was written several years after he and two fellow whistleblowers had been sacked for insubordination. They too were outspoken experts deeply committed to the public good – just like those sacked in New Brunswick.

Report: Jonathan Matthews

Image: Rod Cumberland (left) and Eilish Cleary (right)