Investigative journalist exposes vacuous scholarship underlying FOIA denial

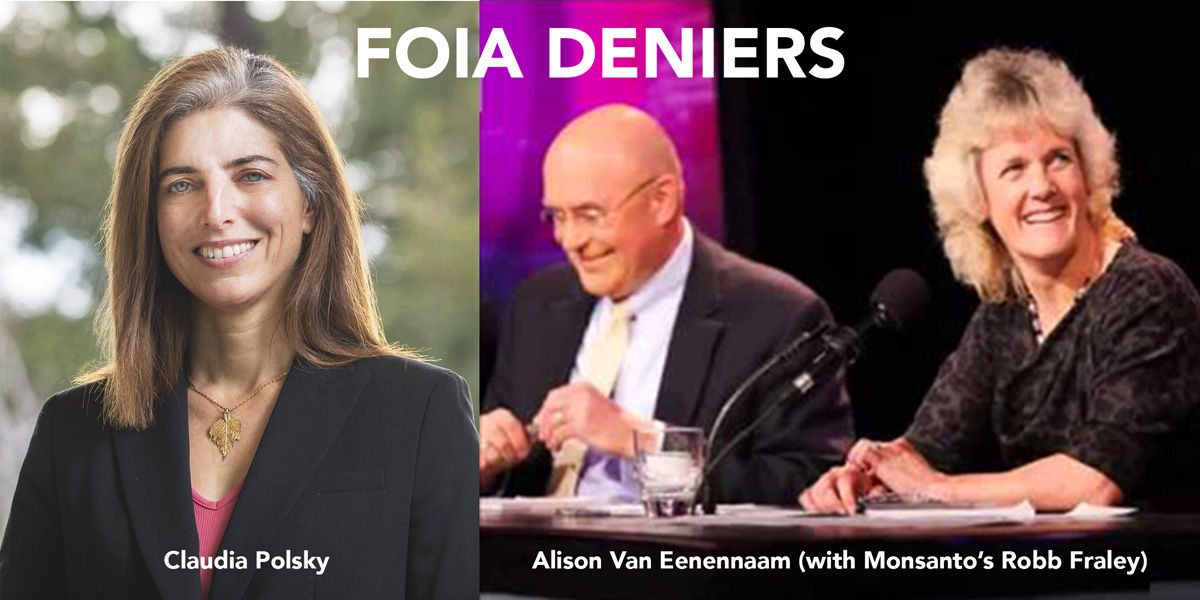

The investigative journalist Paul Thacker has published a scathing article about UC Berkeley law professor Claudia Polsky's quest to exempt publicly funded academics from open public records laws – the laws that US Right to Know has made such brilliant use of to investigate the links between certain university researchers and industry.

Thacker exposes how Polsky's influential law review on the issue, far from being a weighty piece of scholarship, is carefully crafted advocacy for the limits on state freedom of information acts (FOIA) that are advanced by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) and Monsanto. Monsanto's Cami Ryan even calls FOIA “a four-letter word”.

A California bill (AB700) sponsored by UCS and based on Polsky's law review has recently been halted by strong opposition from journalism and public interest groups, but similar attempts to limit FOIA in other states may be attempted.

Thacker shows in his article how Polsky's law review cites the former Monsanto employee Alison Van Eenennaam, who is now a professor at UC Davis, as a key example as to why academics should be exempted from scrutiny — with Polsky implying Van Eenennaam was so distressed by USRTK’s FOIA for her industry-linked emails that “she may retreat wholly into the ivory tower”.

In reality, this supposed shrinking violet continues to be a very active advocate for genetically engineered crops and animals. And Thacker gives some revealing examples of Van Eenennaam’s past advocacy.

These include being a spokesperson for the biotech industry marketing website GMO Answers, and flying to Washington DC to discuss genetically engineering animals with Congress, sponsored by the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a corporate-funded libertarian lobby group with a long history of promoting GMOs and downplaying the dangers of smoking and climate change.

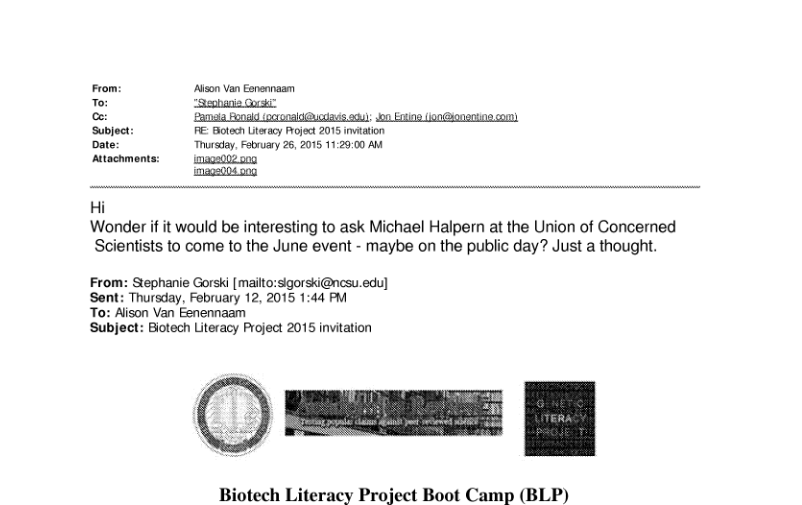

Another telling example of how integrated this public scientist is with corporate PR is her partnering with then Monsanto Vice President Robb Fraley in a public debate against GMO critics. For this debate, FleishmanHillard, the Monsanto PR firm now under investigation for its shady tactics, edited Van Eenennaam’s remarks and coached her on how to “win over people in the room”, in coordination with Fraley and other Monsanto executives. And, of course, we only know about much of this collusion with industry because of USRTK’s FOIA work on Van Eenennaam.

Polsky’s morphing of what Thacker calls “Dr Van Eenennaam’s scandalous behaviour” into an example of harassment of a public academic is highly reminiscent of how UCS’s Michael Halpern has characterised as “FOIA bullying” USRTK’s open public records enquiries into University of Florida professor Kevin Folta’s industry connections.

And funnily enough, something that we came across among the emails released by USRTK’s FOIA work was Alison Van Eenennaam suggesting UCS’s Michael Halpern should be invited to the “biotech literacy project boot camp” at UC Davis — training secretly funded by industry to help get journalists onside on the GMO issue. This was almost certainly because Halpern was seen as a potential ally because of his attacks on USRTK and his work to limit FOIA.

It would be interesting to know the extent of any cooperation between Halpern, Van Eenennaam and Polsky in the campaign to exempt publicly funded academics from open public records laws in California.

That’s the kind of thing that FOIA might help uncover, which is precisely why some are so keen to limit such disclosures.

---

When taxpayers fund research, they have a right to see the work

Paul D. Thacker

Medium.com, 20 Jun 2019

https://medium.com/@thackerpd/when-taxpayers-fund-research-they-have-a-right-to-see-the-work-50173bcb1251

[links to sources and illustrations at the URL above]

* End the FOIA denial: What is going on with the UC Berkeley professor who argues against California rights to use Freedom of Information Act requests?

If you’ve ever wondered why people tell so many lawyer jokes, cast your eye on some recent guffaws by Claudia Polsky, a law professor at UC Berkeley. In the last couple of years, Ms. Polsky has gone on a tear across California, promoting the notion that the public doesn’t have the right to examine documents of public employees at taxpayer funded universities.

Perhaps it’s because Ms. Polksy is herself an employee of a public university that she is so alarmed that the public uses freedom of information laws to access university emails. Regardless, recent news articles clearly explain why these records can be so important in holding the powerful accountable. This February, the Los Angeles Times ran a front-page story that exposed emails by a University of Massachusetts professor, who thinks pollution is good for us, collaborating with Trump officials to change pollution regulations. Accessing another professor’s emails, The Washington Post reported that an attorney representing the payday-lending industry paid a Georgia academic to write studies that found these loans are not harmful to the public.

Ms. Polsky’s campaign reached peak advocacy success earlier this year when Assemblywoman Laura Friedman introduced AB700, a bill that proposed to fix the problems that Ms. Polsky says threaten taxpayer funded academics. “AB700 is a careful solution that I’ve endorsed along with 180 academics across California, in every academic discipline,” Ms. Polsky told California legislators at the bill’s hearing. But the words “careful” and “solution” might not be the best descriptors.

Within weeks, around a dozen journalism, civil rights, and environmental organizations came out against the bill, including the California News Publishers Association, American Civil Liberties Union, and Greenpeace. Turning Ms. Polsky’s portrayal of the bill on its head, Nancy Barnes, the Senior Vice President of News and Editorial Director at NPR, wrote that AB700 was “dangerous” not “careful.” In several paragraphs, the NPR executive also pointed out that many of the “solutions” the bill proposed to fix were already part of the law. Oops.

Four editorials against AB700 had already appeared in California newspapers, and Ms. Barnes’ letter, with its scorching content, would have led to a downpour of opposing opinions. Likely sensing political storm clouds on the horizon, Assemblywoman Friedman withdrew the bill hours after the letter emerged.

Undeterred, Ms. Polsky then appeared on NPR’s “On the Media” where she continued her quarrel. Under her UC Berkeley law professor title, Ms. Polsky published a UCLA Law Review that she is now shopping around as proof that we need to change public records laws and create an exclusive legal carve out for her and fellow professors. She also dangled her university law professor title in front of California lawmakers while lobbying them to pass AB700.

But on NPR, Ms. Polsky ignored how university employees influence lawmakers and tried to shift the discussion to coercion. “This is where we get into my basic argument which is that universities are different,” she told NPR. “They don’t have coercive power over anyone in a way that undergirds public records laws.”

If “coercive power” is the standard, does she mean journalists shouldn’t access records to investigate mismanagement or corruption by government social workers, school administrators or employees at public water works? We don’t know, because Ms. Polsky asserts without explaining.

Ms. Polsky’s new advocacy against the public’s right to access taxpayer financed research also represents a swift — and recent — about face for the UC Berkeley professor.

In 2017, Ms. Polsky sued a California agency on behalf of a fellow Berkeley academic to force them to release research on harm caused by cell phones. After winning the lawsuit, she appeared on local TV where reporter Julie Watts asked if the documents should be public because taxpayer dollars paid for the research.

“Absolutely, Julie,” Ms. Polsky responded to the reporter. “This is your money, my money, viewers money. Taxpayer funded, scientific research over a period of years resulted in a review of the scientific literature about cell phone risk and production of a document that was supposed to reach the public, informing people about how to reduce risk from cell phone use.”

Are you following this thinking?

If you’re wondering why Ms. Polsky has such a convoluted understanding of public records, take a gander at her UCLA Law Review piece. Coming in at 84 pages, with 250 footnotes, it seems a weighty piece of scholarship. But closer examination finds Ms. Polsky has not bothered to read the academic literature on freedom of information (FOI) laws before typing up her paper.

At an April conference of the National Freedom of Information Coalition, professor David Cuillier with the University of Arizona School of Journalism cited dozens of research studies on FOI and how states handle records requests. In many instances, states are slow to respond to records requests and charge exorbitant fees for taxpayers to see public documents. Cuillier notes that these studies are “just a sampling of the growing body of research accumulated in just the last 20 years.”

But Ms. Polsky doesn’t cite any of this research, nor does she seem to have stumbled across anything written by Mr. Cuillier, including several books and papers. She also fails to cite a recent Knight Foundation survey of public records experts, who said they face lengthy delays, ignored requests, and excessive fees when they demand that their public universities and state agencies produce public documents.

The reason Ms. Polsky has missed all this research is rather obvious: research in the field doesn’t support Ms. Polsky’s narrative. In another example, Ms. Polsky missed a 2015 Center for Public Integrity report that gave California an “F” for granting taxpayers access to public records.

Ignoring inconvenient research should have simplified Ms. Polsky’s task of writing a law review that claims the public harms public academics by asking to see their public records. But even in the text, she can’t seem to get her facts straight. In the most glaring example, she cites UC Davis researcher Dr. Alison Van Eenennaam, who claims a public records request damaged her ability to speak up about GMO technology. Ms. Polsky writes, “Professors distressed to be targeted by [FOI] requests may, instead, persist in their lines of academic research but forswear expertise-based engagement with the broader public and retreat wholly to the ivory tower.”

This is pure hogwash.

Dr. Van Eenennaam is a vocal advocate for GMO technology who often flies around the country to promote GMO research and is a spokesperson for GMO Answers, a public relations website launched by Monsanto and Bayer. In one example of Dr. Van Eenennaam’s “expertise-based engagement with the broader public”, she flew to DC in 2012 to discuss GMO technology with Congress. Her talk that day was sponsored by the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a corporate financed nonprofit with a long history of misleading the public on the dangers of smoking and climate change.

In another example, Dr. Van Eenennaam partnered with Monsanto executive Robb Fraley in a public debate against GMO critics. For this debate, FleishmanHillard, a Monsanto PR firm, edited Dr. Van Eenennaam’s remarks and helped her coordinate with Fraley and other Monsanto executives.

Emailing Dr. Van Eenennaam, a FleishmanHillard employee wrote, “This will help you better understand what are the key things our team should consider as we work to win over the people in the room, as well as all of those consumers in the NPR rebroadcast of the event.”

By now, you might be wondering how Ms. Polsky published this melodrama in the UCLA Law Review without citing important academic papers, and morphing Dr. Van Eenennaam’s scandalous behavior into an example of academic harassment. That’s likely because the UCLA Law Review is edited by law students. Perhaps Ms. Polsky snuck a rather flimsy paper past students, who were distracted by homework?

To better understand Ms. Polsky’s crusade against public information requests, I’ve filed my own public records request to see how she has influenced changes to public records laws. Since she also seems to ignore academic experts in the field, I’m also interested in where she got her ideas and sources for her quirky law review.

In recent years, several law professors have been disparaged for making public statements that coincidentally benefitted their private clients. Laurence Tribe, professor at Harvard Law School, mentor to Barack Obama, and one of the most venerated legal scholars in the country, was excoriated for attacking President Obama’s environmental agenda while also representing Peabody Energy. Few law schools require professors to disclose their private clients, but legal scholars have argued for decades that law professors and law review authors should disclose their clients.

The only law school that I am aware of that requires their professors to disclose their outside clients is Harvard. This only happened because, when I worked in the Senate, I helped their attorneys to create a more transparent system. So I’m also asking to see who Ms. Polsky might be representing, and if this might conflict with her purported academic scholarship against public records requests.

Having made multiple public records requests over several years, I don’t expect a speedy, complete response from UC Berkeley. Unlike Ms. Polsky, I know how public records laws actually work.