New analysis shows EPA relied on secret industry studies, which found ‘no effect’ from glyphosate, rather than published studies, which mostly found the chemical was genotoxic

Many people around the world still struggle to understand how and why the US EPA and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concluded that the herbicide active ingredient glyphosate is not genotoxic (damaging to DNA) or carcinogenic, whereas the World Health Organisation’s cancer agency IARC came to the opposite conclusion. IARC stated that the evidence for glyphosate’s genotoxic potential is “strong” and that glyphosate is a probable human carcinogen.

These agencies’ opposing views on glyphosate’s genotoxic potential played a crucial role in their differing conclusions about glyphosate’s carcinogenicity, since genotoxicity is one of two mechanisms through which glyphosate was deemed by the IARC to be carcinogenic (the other being oxidative stress).

Now a new peer-reviewed article answers the question of how and why the US EPA and EFSA reached diametrically opposed conclusions to IARC about glyphosate’s genotoxicity.[1] The article shows that the EPA relied on unpublished industry studies, 99% of which found that glyphosate was not genotoxic, whereas IARC relied on published studies, 74% of which found that glyphosate was genotoxic.

The EPA's "no genotoxicity risk" judgement on glyphosate was essential to its "no carcinogenic risk" classification of the chemical. The article shows that only by framing and constraining its genotoxicity assessment in a highly selective and biased way was the EPA able to conclude that glyphosate was not genotoxic. It also demonstrates that the EPA's cancer classification – as well as EFSA’s, which was based on the same data and was reached in a similar way – is scientifically baseless. Overall, the article shows that the way pesticides are assessed for risk is not fit for purpose and exposes people and the environment to unacceptable risks.

The paper is authored by Dr Charles Benbrook and is published in Environmental Sciences Europe.

The article’s key findings in detail are as follows.

1. EPA relied on secret and biased industry studies, whereas IARC used published studies

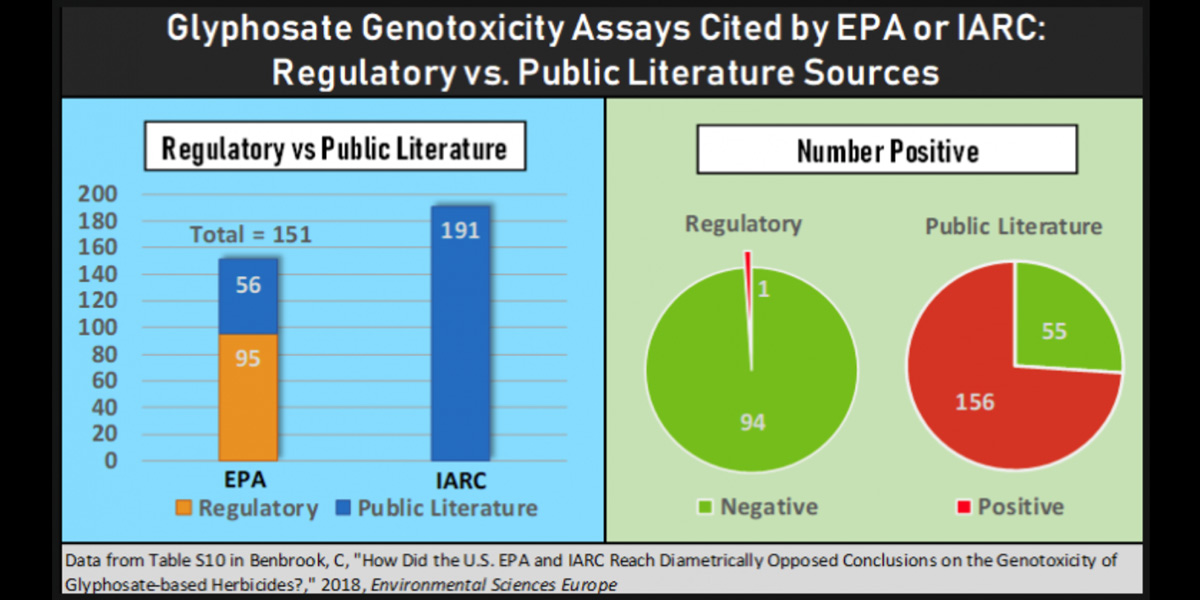

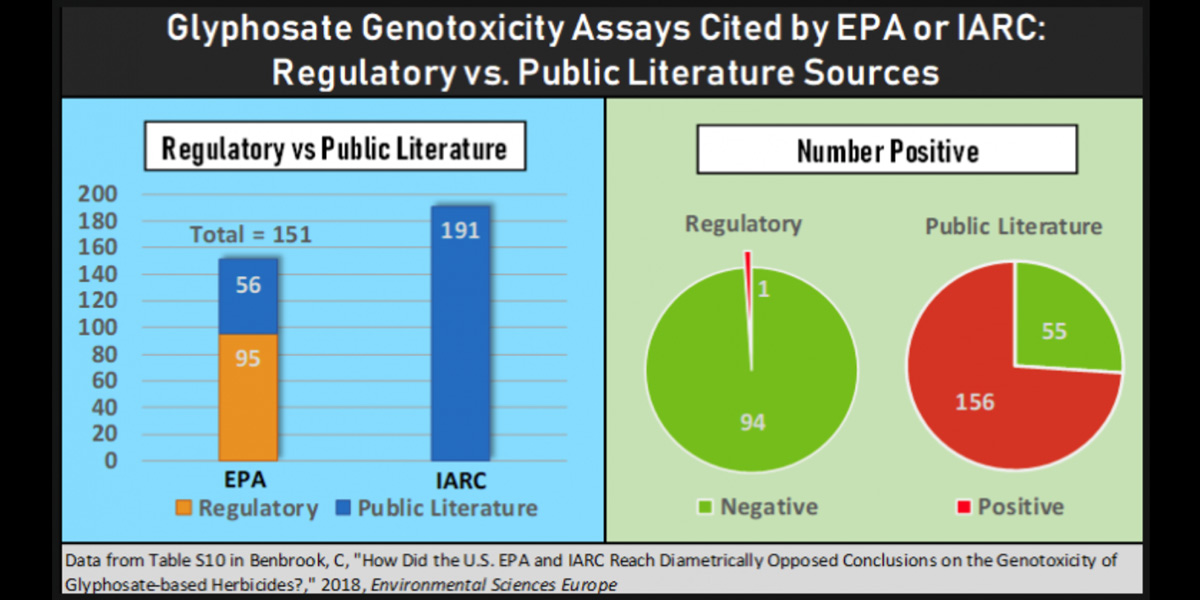

While IARC referenced only peer-reviewed studies and reports available in the public literature, EPA relied heavily on unpublished regulatory studies commissioned by pesticide manufacturers. In fact, 95 of the 151 genotoxicity assays cited in EPA’s evaluation were from industry studies (63%), while IARC cited 100% public literature sources.

There is a stark difference in the outcomes of industry-sponsored assays versus those in the public literature. Of the 95 industry assays taken into account by EPA, only one reported a positive result (i.e. that glyphosate had a genotoxic effect), or just 1%. Among the total 211 published studies (right circle in the graphic below), 156 reported at least one positive result, or 74%!

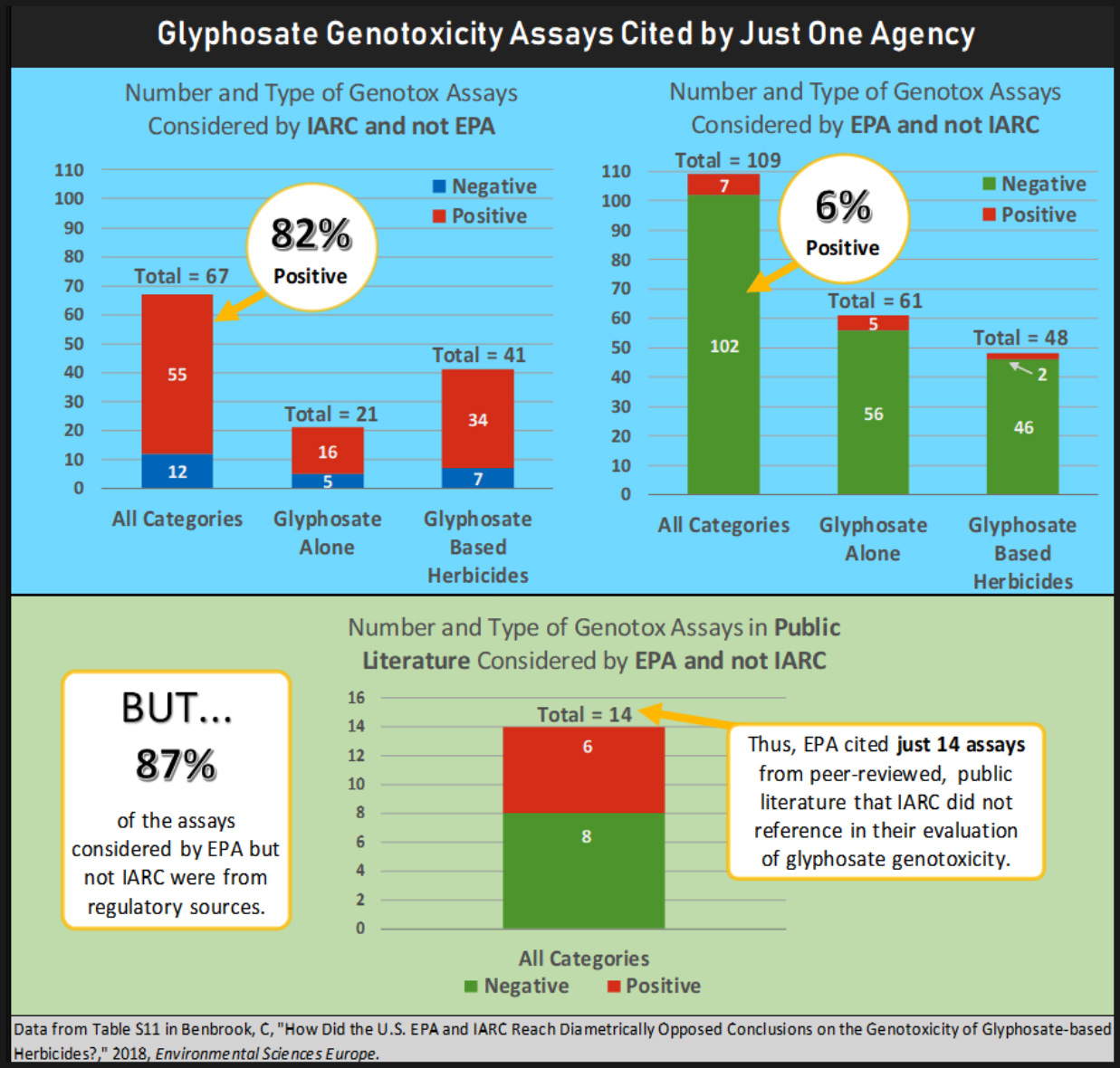

A closer look at the assays referenced by EPA but not IARC, and by IARC but not the EPA, also helps explain why EPA and IARC reached opposite conclusions.

EPA cited 109 total assays not included in the IARC report, 87% of which were regulatory studies commissioned by industry, and all but one was negative (i.e. no genotoxic effect).

IARC included the results from 67 assays not included in EPA’s analysis, all of which were from peer-reviewed publications, and 82% of which had at least one positive result for genotoxicity.

2. EPA analyzed a substance that almost no one is exposed to, whereas IARC looked at the real thing

Another important difference is that EPA focused its analysis on glyphosate in its pure chemical form, or “glyphosate technical”. The problem with that is that almost no one is exposed to glyphosate alone. Applicators and the public are exposed to complete herbicide formulations consisting of glyphosate plus added ingredients (adjuvants). The formulations have repeatedly been shown to be more toxic than glyphosate in isolation.

IARC, in contrast to the EPA, placed considerable weight on 85 studies focused on formulated glyphosate-based herbicides that people actually use and are exposed to. A massive 79% of the glyphosate-based herbicide assays published in the public literature reported one or more positive result.

While the EPA did list studies on formulated glyphosate-based herbicides in Appendix F of its report, EPA acknowledges it placed little to no weight on glyphosate-based herbicide assay results.

This difference is reflected in the overall percent of positive assays. Just 24% of the 151 assays cited by EPA reported positive results, while 76% of those cited by IARC had at least one positive result.

3. The EPA didn’t consider occupational exposure, whereas IARC did

The EPA’s analysis was limited to typical dietary exposure to the general public as a result of legal uses on food crops, and did not address occupational exposure and risks.

IARC’s assessment encompassed data from typical dietary, occupational, and elevated exposure scenarios. Elevated exposure events caused by spills, a leaky hose or fitting, or wind are actually common for people who apply herbicides several days a week, for several hours, as part of their work.

“Important” article – journal editor

In an unusual step, the editor-in-chief of Environmental Sciences Europe, Prof Henner Hollert, and his co-author Prof Thomas Backhaus, weighed in with a strong statement in support of the acceptance of Dr Benbrook’s article for publication. In a commentary published in the same issue of the journal, they wrote, “We are convinced that the article provides new insights on why different conclusions regarding the carcinogenicity of glyphosate and GBHs [glyphosate-based herbicides] were reached by the US EPA and IARC. It is an important contribution to the discussion on the genotoxicity of GBHs.”

Profs Hollert and Backhaus explained that it is usual practice to send manuscripts submitted to the journal to 2-4 peer reviewers. But due to the fact that the discussion on the carcinogenicity of glyphosate has become a “toxic issue”, the journal sent the article to no less than 10 reviewers, all but one of whom recommended publication.

Journal editor and co-author call for reform of pesticide approvals

In their commentary, Profs Hollert and Backhaus offered a list of “lessons to be learned” from Dr Benbrook’s article for the risk assessment of pesticides and other chemicals. Those lessons include recommendations for reform – many of which have long been demanded by GMWatch and other NGOs. In sum, these are:

* Studies relating to both glyphosate and glyphosate-based herbicide formulations must be taken into account in risk assessments.

* The problem formulation step of the risk assessment is critical to an understanding of the outcome. Thus it must be made clear to everyone, including laypersons, which substance is being assessed – as well as which exposure scenarios, endpoints, and protection goals are being considered.

* As different evaluators give different weights and reliability scores to different studies, all studies used in the risk assessment and the data underlying them must be made public and thus available for independent scrutiny. Thus the problem formulation, assessment protocols and data analysis also must be published. Pesticide assessments should implement the systematic review methodology already promoted by EFSA

* New studies must be registered, in the same way as clinical trials, to ensure that ‘no effect’ findings (which are notoriously hard to publish in journals), as well as unwelcome results, are equally considered in the assessment.

* Given that glyphosate-based herbicide formulations are more toxic than glyphosate alone, mixture effects must be considered during the risk assessment, in line with Article 4.3(b) of the EU’s pesticide regulation 1107/2009. However, this poses a challenge to transparent assessment, since the co-formulants in commercial pesticide formulations are not generally disclosed by manufacturers and are largely unknown.

NGOs and EU Parliamentary committee back editor’s call for reform

GMWatch welcomes Dr Benbrook’s article and the commentary by Profs Hollert and Backhaus as highly informative analyses of what is wrong with the regulatory assessments of pesticides and how the system needs to change. These new publications reinforce and in many aspects reflect the demands for reform of the pesticide risk assessment process put forward last year by Citizens for Science in Pesticide Regulation, a coalition of 120 NGOs, including GMWatch.

Further support for many of these measures comes from the European Parliament’s PEST Committee, which was set up in response to the concerns raised by the European Citizens’ Initiative to ban glyphosate, the Monsanto Papers (internal Monsanto documents disclosed in cancer litigation in the USA revealing how industry has subverted science), and the discrepancies in the cancer assessments of glyphosate between the European institutions and the IARC.

Note: Since September 2017, Dr Charles Benbrook has served as an expert witness in litigation involving the contribution of Roundup (a glyphosate-based herbicide) to non-Hodgkin lymphoma. He testified on behalf of Lee (Dewayne) Johnson during his trial in San Francisco in the summer of 2018.

Reference

1. Benbrook C (2019). How did the U.S. EPA and IARC reach diametrically opposed conclusions on the genotoxicity of glyphosate-based herbicides? Environmental Sciences Europe, January 15. DOI: 10.1186/s12302-018-0184-7. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12302-018-0184-7