People who think pesticides might have something to do with the microcephaly outbreak in Brazil are being attacked as irrational conspiracy theorists. Claire Robinson takes a closer look at who’s peddling the myths

I recently published an article on reports by the Argentine doctors’ group, Physicians in the Crop-Sprayed Towns, and the Brazilian public health researchers’ group Abrasco, which raised the issue of the potential role of the larvicide pyriproxyfen in the apparent surge in babies born with birth defects involving abnormally small heads (microcephaly). Pyriproxyfen is added to drinking water stored in open containers to interfere with the development of disease-carrying mosquitoes, thus killing or disabling them.

The Ecologist published a version of my article which, together with the original publication on GMWatch, quickly went viral, triggering a lot more media coverage. This in turn met with a furious backlash involving what has seemed at times like a “shouting brigade” condemning anyone who thinks the Argentine report worth taking seriously.

Yet at times this chorus of condemnation has been extraordinarily hypocritical, condemning the Argentine doctors as enemies of fact and accuracy while getting the most basic of facts wrong about what the doctors are actually suggesting.

Pesticide defenders invent “pesticide causes Zika” conspiracy theory

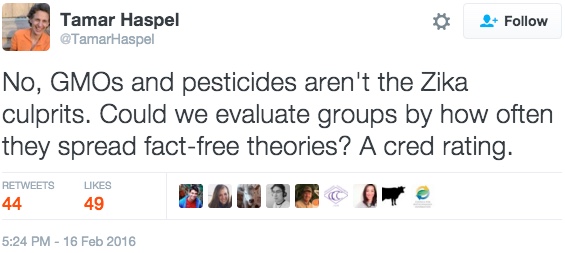

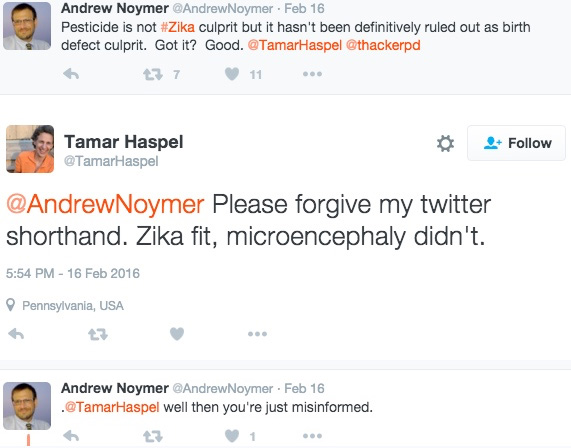

Take, for instance, the Washington Post food columnist, Tamar Haspel. Haspel tweeted: “No, GMOs and pesticides aren't the Zika culprits. Could we evaluate groups by how often they spread fact-free theories? A cred rating.”

Andrew Noymer, a social epidemiologist at the University of California, Irvine, replied: “Pesticide is not Zika culprit but it hasn't been definitively ruled out as birth defect culprit. Got it? Good.”

In response to Noymer’s challenge, Haspel claimed that she was just using Zika as Twitter “shorthand” for microcephaly! Noymer retorted, “Well then you’re just misinformed.

It wasn’t just Haspel who seemed to accuse the supposed “conspiracy theorists” of linking the pesticide to Zika. Grist food writer Nathanael Johnson also appeared to fall into the trap with a headline attacking a “bogus theory connecting Zika” to the pesticide industry. But the Argentine doctors only ever suggested the larvicide pyriproxyfen might be a culprit in microcephaly. Nobody ever claimed pesticides cause the Zika virus!

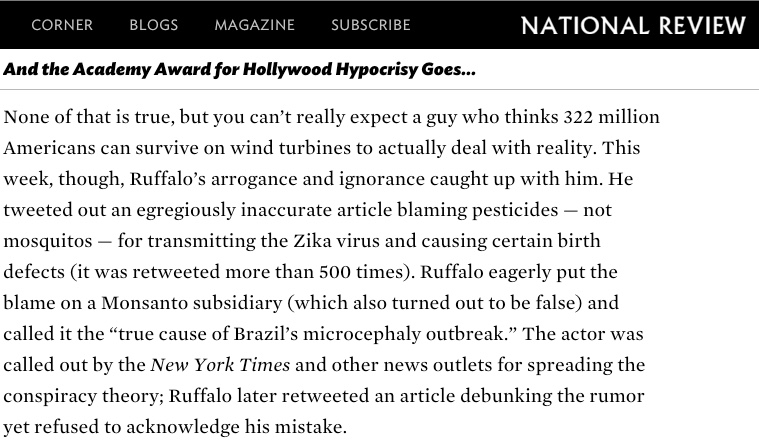

Another well-known GMO supporter, Julie Kelly, made a similar mistake when she damned the Hollywood actor Mark Ruffalo for tweeting what she said was an “egregiously inaccurate” article that blamed “pesticides – not mosquitos – for transmitting the Zika virus”.

Just good friends

This is not to say that some of the initial coverage of the pesticide theory didn’t suffer from real inaccuracies. One red herring was set running by the Argentine doctors themselves when they wrongly identified the company that makes the larvicide as a subsidiary of Monsanto.

In fact, Sumitomo Chemical is a long-term strategic partner of Monsanto’s – they’ve been working together for nearly two decades, but Monsanto doesn’t own the company. Even so, it’s a perhaps understandable error given the closeness of the companies’ cooperation in Brazil and Argentina. In any case, it’s an error that I was careful to avoid in my Ecologist piece, which correctly identified the larvicide manufacturer as only a strategic partner.

Nevertheless, it’s an error that was seized upon by Nathanael Johnson, for instance, with his headline, “A bogus theory connecting Zika virus to Monsanto could give mosquitoes a boost”.

Ironically, that headline, as we’ve noted, is more misleading than the error about the extent of the Monsanto connection.

"Pesticides could be involved" – leading virologist

What is also misleading about Johnson's headline is the suggestion that the pesticide theory (in relation to microcephaly, of course, not Zika) can be batted off as “bogus”. The idea that this particular pesticide – and/or other pesticides – could be linked to the birth defect problem in Brazil is not something that can simply be dismissed out of hand.

Although it’s been claimed that Dr Francis Collins, director of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, “spoke out against the ‘sketchy’ report” of the Argentine doctors, Collins actually described their theory not as bogus but as “interesting”.

And the biologist Dr Pete Myers, in an editorial comment posted on the online news service Environmental Health News, pointed out that the reason the pesticide hypothesis is, as Collins rightly says, “sketchy”, is the lack of adequate investigation of pesticides before they are released on to the market:

“[These are] dueling hypotheses [as to whether the Zika virus or the larvicide is responsible for the microcephaly increase] with great consequences for getting it right, or wrong. We would be in a better position to make the choice if pesticides were tested more rigorously before being used.”

In fact, one of the world’s leading virologists, Dr Leslie Lobel, recently told The Guardian that it is not clear that the microcephaly cases in Brazil are linked to the Zika virus and that there was “a strong possibility pesticides could be involved and this needed to be studied”.

The reason it needs to be studied is because, as Myers’ points out, there’s a relative lack of hard and independently generated data on pesticides like pyriproxyfen, thanks to an inadequate regulatory system. The Argentine doctors are not to blame for this regulatory failure and they should not be censured for flagging up questions about the chemical.

Axes to grind

Why are some people so keen to dismiss the doctors’ suggestion out of hand?

It’s been suggested that those flagging up the possibility of a connection between pyriproxyfen and microcephaly have a hidden agenda. For example, Professor Andrew Batholomaeus, one of the “experts” quoted by the Science Media Centre of Australia in defence of the larvicide’s safety, said: “Journalists covering this story would do well to research the background of those making and reporting the claims as the underlying story and potential public health consequences may be far more newsworthy than the current headlines.”

But it’s surely no surprise if Argentine physicians, who have had to deal at first hand with the suffering caused by the GMO soy revolution in Argentina with its accompanying pesticide onslaught, should be particularly alert to the role of pesticides in health and development issues in Latin America – and suspicious of the safety claims of chemical corporations.

The doctors say their local communities are facing an exploding health crisis, which includes children suffering unusual birth defects. And in neighbouring Brazil the country’s National Cancer Institute says the release of GM crops has helped make the country the largest consumer of agrochemicals in the world.

Industry-friendly attackers

Also, some of those leading the attacks on the pesticides hypothesis could also be accused of having an agenda. Julie Kelly, for instance, uses her National Review article to attack Mark Ruffalo not just for drawing attention to the larvicide theory but also over his campaigning on climate change and fracking, his support for sustainable energy, and his publicly confronting the CEO of Monsanto over the impact of his company’s products.

Kelly, who is married to a lobbyist for the agricultural commodities giant ADM, is a self-declared member, along with Monsanto personnel, of the Kevin Folta “fan club” – Kevin Folta being the GMO-loving/Roundup-drinking scientist who denied having any links to Monsanto even though he’d received $25,000 from the company for his biotech communication programme and had other notable industry connections besides.

Interestingly, Tamar Haspel appears far from keen to explore the ties between companies like Monsanto and academics at public universities like Kevin Folta, and has herself been accused of collaborating closely with the agrochemical industry and of batting for Monsanto.

And perhaps the most virulent attack on the Argentine doctors, published predictably in Forbes, was contributed by another Folta fan. Kavin Senapathy also regularly co-authors pieces with Henry Miller, a climate skeptic and staunch defender of DDT and other controversial pesticides, not to mention the tobacco industry.

So where does this leave us?

Yes, the Argentine doctors and some of their supporters may be said to have an agenda, but as we have seen, that charge can just as easily be levelled against some of those keen to debunk their concerns.

The connection to Monsanto may have been overstated by the doctors, and even more by some news outlets, but it wasn’t invented – Sumitomo Chemical is Monsanto’s long-term strategic partner.

There has also been a misplaced attack on those of us who have drawn attention to the concerns of the Brazilian public health researchers about pyriproxyfen and other chemicals. I’ll be looking at that in a subsequent article.

And as one of the world’s leading virologists has also flagged up the need to take seriously that notion that pesticides could be involved, I’m going to be looking more at this critical issue, including what scientists do and don’t know about pyriproxyfen.