Protesters have successfully blocked a seed-processing plant in Malvinas, Argentina for over two years. Despite strong national and international support, the fight continues. Report by Ciara Low

"Cordobeses (residents of Córdoba) will be proud to have one of the most important (seed-producing) plants in the world,” Monsanto’s website claims. “The more than one thousand employees of Monsanto Argentina are proud and thankful to be a part of the community of Malvinas, Argentina.”[1]

"Cordobeses (residents of Córdoba) will be proud to have one of the most important (seed-producing) plants in the world,” Monsanto’s website claims. “The more than one thousand employees of Monsanto Argentina are proud and thankful to be a part of the community of Malvinas, Argentina.”[1]

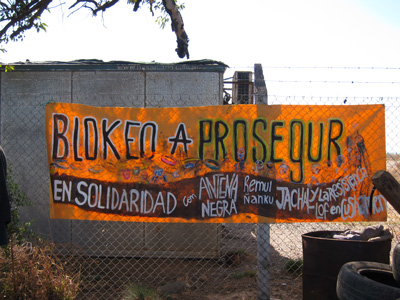

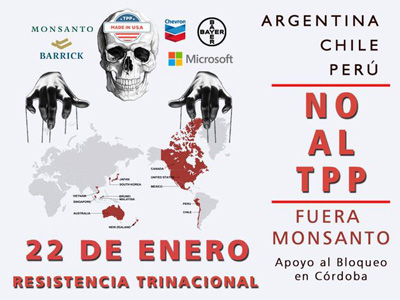

However, it would appear the sentiment doesn’t go both ways. A blockade against the agro-giant Monsanto in Malvinas, Argentina entered its third year in September of last year. The construction of what would be Monsanto’s second largest seed processing plant in Latin America halted in September 2013 when a group of activists blockaded the plant’s five entrances and set up camp. An injunction officially halted construction on the site in January of last year. Recently the protesters received an eviction notice, delivered at the request of Monsanto, but local activists mobilized to strengthen the blockade, and a prosecutor suspended the order.

The two-year anniversary saw over 150 people pass through the camp in support of the blockade. Others gathered in the cities of Córdoba and Buenos Aires to march in support. The message: Monsanto is not welcome here. Despite the strong opposition and legal barriers, Monsanto continues in its attempts to secure the plant’s approval.

Argentinians say ‘no more’

Malvinas is a small town in the northeastern Argentinian province of Córdoba. The area has long been the site of multinational corporate interests: Route A88, which runs past Monsanto’s inactive site, serves plants owned by Coca-Cola, Argentine energy company YPF, and Bayer. Monsanto’s proposed plant would be responsible for producing and treating corn seed.[1]

Malvinas is a small town in the northeastern Argentinian province of Córdoba. The area has long been the site of multinational corporate interests: Route A88, which runs past Monsanto’s inactive site, serves plants owned by Coca-Cola, Argentine energy company YPF, and Bayer. Monsanto’s proposed plant would be responsible for producing and treating corn seed.[1]

Monsanto announced plans to begin construction of the plant in January 2013, following approval by the Malvinas City Council.[2] Public protest ensued. When marches in Buenos Aires and letters to the provincial council failed to produce results, protesters blockaded the plant’s five entrances. Five months later their efforts were legally reinforced when a labour appeals court ruled construction on the site was unconstitutional,[3] suspending it until public consultation and an environmental impact assessment are completed. Activists have been camped at the plant’s entrance for over two years now as Monsanto attempts to secure legal permission to continue construction.

Monsanto responsible for GM boom

Monsanto’s presence in Argentina is nothing new. The world’s largest seed producer first began producing plastics there in 1956, and manufactured chemicals such as Agent Orange. Monsanto introduced genetically modified (GM) soy in 1996, quickly changing the nature of agriculture in Argentina. Between 1980 and 2005, the area of land dedicated to soybean production increased from two million to 17 million hectares.[4] Now, GM soy monocultures largely comprise the Argentinean countryside.

The GM boom has been directly responsible for deforestation of native forests and indirect deforestation caused by the relocation of cattle from agriculturally attractive land.[4,5,6] Glenn Ellis, a documentary filmmaker investigating Monsanto in Argentina, remarked, “Not so long ago Argentina topped the world for meat production, but here there was not a cow in sight.”[7] Where Argentina's world-famous cows were once pasture-fed, the GM land grab has pushed them into feedlots and changed their diet from grass to grain.[4]

The GM boom has been directly responsible for deforestation of native forests and indirect deforestation caused by the relocation of cattle from agriculturally attractive land.[4,5,6] Glenn Ellis, a documentary filmmaker investigating Monsanto in Argentina, remarked, “Not so long ago Argentina topped the world for meat production, but here there was not a cow in sight.”[7] Where Argentina's world-famous cows were once pasture-fed, the GM land grab has pushed them into feedlots and changed their diet from grass to grain.[4]

GM crop expansion has driven not only cattle, but also local farmers from the land. GM products are marketed as having cost-saving advantages – higher yields (though this remains controversial) for less labour, encouraging farmers to convert land to soy cultivation and driving large increases in production. However, though higher production translates into an increase in GDP, it is corporations that see the profits, while lower labour costs ultimately translate to job loss for local farmers.

Much like in the US, ‘family farming’ in Argentina is a thing of the past. Local farmers are either unable to compete with the low prices of GM products, or are bought out by bigger business. Argentina is the world’s third largest producer and exporter of soy products.[8] The Argentinean economy is consequently heavily reliant on soy exports, and government support to increase production is strong. Last year, Argentina planted 20 million hectares of soy, the majority provided by Monsanto.[9] The Ministry of Agriculture’s Strategic Agribusiness Plan aims to increase grain production to 160 million tons over the next six years.[10]

Rallying call for opposition is health

While deforestation and job loss are significant consequences of Argentina’s GM boom, the rallying call for the grassroots opposition is health. Despite the existence of laws prohibiting pesticide spraying close to residential areas (laws differ between regions and in some are nonexistent), GM soy is grown next to houses, water sources, workplaces, and schools. There is growing concern about the link between the spraying and the observed increases in cancer rates, birth defects, and miscarriages in areas where GM crops are located. A study conducted by the Ministry of Health found that deaths due to cancer are double the national average in Córdoba province.[11]

One of the attractions of GM crops is the ease of herbicide application. While the genetically engineered seeds survive spraying, Monsanto´s Roundup herbicide kills all other plants and insects in the vicinity. As such, farmers apply it liberally.

Additionally, the use of aerial spraying means that the wind carries herbicides far from their point of origin. A local doctor interviewed by Ellis referred to “an epidemic of birth malformations” in the Chaco province that correlates with the increase in soy plantations in the region over the past 15 years.[7] Such claims are bolstered by a study published in Chemical Research in Toxicology that found that glyphosate, the main chemical ingredient in Roundup, causes birth defects in animal embryos at levels far below those currently used in agricultural spraying.[12] Despite numerous reputable studies highlighting the health risks posed by glyphosate spraying, including the recent report released by the WHO classifying the chemical as a “probable” human carcinogen,[13] Roundup remains widely used at local, national, and international levels.

Camp is constant reminder of ongoing fight

The blockade in Malvinas has become the face of opposition against Monsanto and corporate interests nationally. Where energy wanes between marches and organized events, the camp is a constant reminder of the ongoing fight and the power of grassroots opposition. On the weekend of the blockade´s second anniversary current and returning blockaders, Malvinas residents, and supporters from all over Argentina united to share information and plan the movement´s next steps. Representatives of the Zapatista movement addressed the crowd, lawyers and health professionals from the area explained terminology and debunked the myths surrounding GM crops, and camp members held workshops educating people on alternative, sustainable lifestyles. Music groups rapped about the fight against Monsanto, and capoeira dancers stopped traffic on the highway to hand out informational flyers.

In spite of the blockade, legal setbacks, and the rejection of Monsanto’s first environmental impact assessment last year, the corporation continues to try to restart construction on the Malvinas plant. It is currently seeking amendments to federal laws in preparation for the presentation of its second environmental impact assessment. Meanwhile, Monsanto´s recent attempted eviction notice has ramped up blockaders efforts to rid Malvinas of Monsanto for good. The word is out, people are making noise. The streets of Córdoba and Buenos Aires are ringing with calls for Monsanto´s eviction – “Fuera Monsanto!” The message could not be clearer. However, Monsanto’s immense political power means that more voices may still be needed to ensure that it does not fall on deaf ears.

In spite of the blockade, legal setbacks, and the rejection of Monsanto’s first environmental impact assessment last year, the corporation continues to try to restart construction on the Malvinas plant. It is currently seeking amendments to federal laws in preparation for the presentation of its second environmental impact assessment. Meanwhile, Monsanto´s recent attempted eviction notice has ramped up blockaders efforts to rid Malvinas of Monsanto for good. The word is out, people are making noise. The streets of Córdoba and Buenos Aires are ringing with calls for Monsanto´s eviction – “Fuera Monsanto!” The message could not be clearer. However, Monsanto’s immense political power means that more voices may still be needed to ensure that it does not fall on deaf ears.

Support

The blockade can be contacted via the Facebook group Bloqueo a Monsanto Malvinas Argentinas. ‘Like’ the Facebook page and help get the word out!

See Manu Chau´s recent music video (in Spanish), documenting the history of the blockade.

Ciara Low studied international environmental law and policy at Brown University. She has been living and working in Chile for the past year, and in August 2015 spent three weeks living with fellow protesters at the blockade against Monsanto in Malvinas, Argentina.

References

1. Monsanto. “Nuestros Compromisos: Malvinas Argentinas.” Monsanto. Web.

2. Monsanto. “Noticias y Opiniones: Monsanto en Malvinas Argentinas.” Monsanto. 26 September 2013. Web.

3. Frayssinet, Fabiana. “Argentine Activists Win First Round Against Monsanto Plant.” Inter Press Service. 25 January 2014. Web. http://www.ipsnews.net/2014/01/argentine-activists-win-first-round-monsanto-plant/

4. Reboratti, Carlos. “Un mar de soja: la nueva agriculturaen Argentina y sus consecuencias.” Revista de Geografía Norte Grande 45 (2010): 63-76. Print.

5. Seghezzo et al. “Native Forests and Agriculture in Salta (Argentina): Conflicting Visions of Development.”The Journal of Environment Development 20 (2011): 251-277. Print.

6. VIB. Fact Series: Herbicide Resistant Soybean in Argentina. 2013.

7. Ellis, Glenn. “Argentina’s Bad Seeds.” Al Jazeera English. 14 March 2013. Web. http://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/peopleandpower/2013/03/201331313434142322.html

8. USDA. “Oilseed, Soybean 2014.” Crop Explorer. Web.

9. USDA. “Argentina Soybeans 2014: Commodity Intelligence Report.” Office of Global Analysis. 14 Jan 2014. Web.

10. Ministerio de Agricultura, Ganader֑ía y Pesca. Argentina Lider Agroalimentario. 16 September 2011. Print.

11. Gobierno de la Provincia de Cordoba. “Se presenta el informesobre cancer en la Provincia.” Portal de Noticias. Web.

12. Carrasco, Andrés et al. “Glyphosate-Based Herbicides Produce Teratogenic Effects on Vertebrates by Impairing Retinoic Acid Signaling.” Chemical Research in Toxicology 23 (2010): 1586-1595. Print.

13. Guyton et al. Carcinogenicity of tetrachlorvinphos, parathion, malathion, diazinon, and glyphosate. The Lancet Oncology 16(5) (2015): 490–491. http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lanonc/PIIS1470-2045%2815%2970134-8.pdf